The guy who founded Squat University knows a lot about squatting.

Dr. Aaron Horschig is a sports and orthopedic physical therapist, certified strength and conditioning specialist, USAW Olympic weightlifting competitor and level 1 coach, plus he’s an author – his first book, The Squat Bible, will be released in March of 2017.

His specialty, of course, is squat mechanics, and BarBend caught up with him to ask some of our most burning questions.

The doctor is in.

BarBend: You’ve coached a lot of different kinds of professional athletes – Olympic weightlifting, functional fitness, football, baseball, basketball, soccer. What’s the most common squat issue you’ve noticed across those audiences?

Dr. Aaron Horschig: Across the board, it’s knee pain. That’s because the knee is set in between two areas that a lot of people have problems with: the ankles and hips. If they’re not doing their jobs – say, there’s poor hip coordination or stiff ankles – the knee won’t be moving as it should and it’ll have problems.

A good example is patellar tendonitis among CrossFit® athletes. If someone does three hundred pistols in a WOD and their ankles aren’t extremely mobile, their knee is going to take the brunt force of the movement and eventually, it’ll get overuse injuries. A lot of the time, solving knee pain can simply mean improving ankle mobility.

BB: So, what’s the most common form tip you find you have to give athletes when they’re squatting?

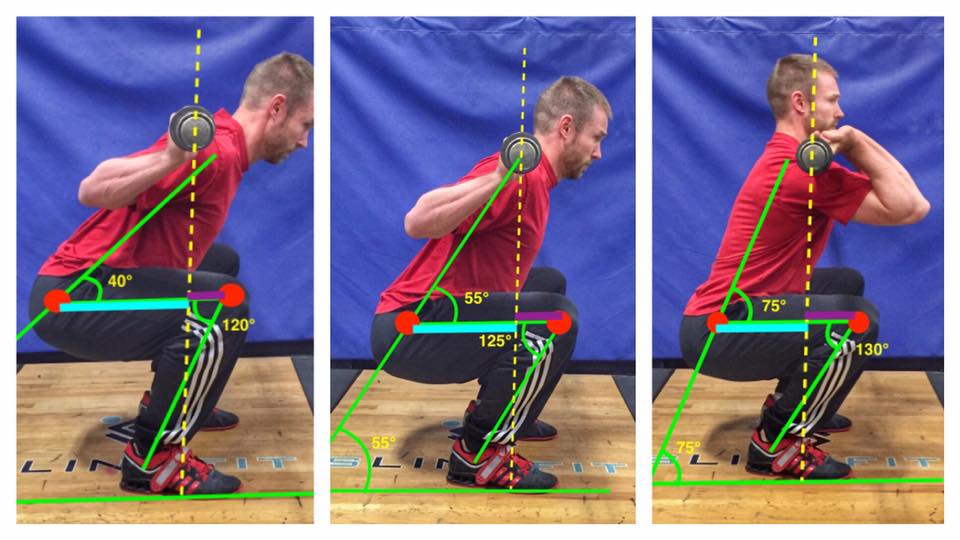

AH: Every single squat must start at the hips, and then you need to stay in balance. And you know the athlete is in balance when the bar tracks over the middle of the foot. If that bar is out of alignment with the middle of the foot, the athlete is off balance and unable to produce efficient force and power.

If you’re watching someone squat from the side and they start by pushing their knees forward at the very start of the descent, a lot of times that bar will travel toward their toes. On the other hand, if you start a squat with too much hip hinge, the chest will drop forward and the bar will again drift toward the toes. It becomes like a “good morning squat.”

So it’s all about finding that right amount of hip hinge. Drive the hips back while the bar remains over the middle of the foot, and then just squat straight down.

BB: What are some of the basic anatomical differences on which you’ll decide the right kind of squat for someone’s body type?

AH: Like I said, the big thing is if the bar is tracking over the middle of your foot.

Let’s say you have two friends, Friend A and Friend B. Friend A has a very long torso and B has a very short torso, so right off the bat they’re going to have two very different squats. A will have a more inclined trunk, and B will be much more upright. Friend A might lose sleep worrying that doesn’t squat as upright as Friend B, but their bodies are different. No two squats look exactly alike. What’s important is the tracking of the bar.

The same thing goes for ankle mobility. If Friend A has great ankle mobility, he’ll be able to squat deep with an upright chest. If Friend B has stiff ankles, his knees won’t translate over his toes very far and his trunk will lean forward to keep the bar over the middle of the foot. And that’s okay!

To find out if a squat is right for that person, view it from the side. If the bar is over the middle of the foot, then they’re moving as mechanically efficient as their body can. That’s the golden rule.

BB: So would you say Friend A and Friend B should do different types of squats for their body type?

AH: I really think that, barring a really significant mobility issue or injury history, the back squat can be right for everyone. The thing is that yours might not look the same as everyone else’s.

BB: Let’s talk butt wink. Why are so many people concerned about it? Is it that big a deal?

AH: Butt wink primarily talks about a posterior pelvic tilt during the squat. For some people, as they descend into the squat, their pelvis naturally pulls under their body. It’s a posterior rotation of the pelvis itself.

Theoretically, when it’s excessive, it leads to a loss in lumbar spine stability. That’s not great, because you usually want as neutral a lumbar curve as possible. If the lumbar spine is pulled into a flexed position, it puts a lot of harmful forces on the discs in between the vertebrae.

The fear of butt wink is that if it’s excessive and causes that loss of lumbar stability then over time – we’re talking after many reps, sets, and years – it could cause a disc bulge in the lumbar spine. Theoretically.

Now, a lot of people, as soon as they see a little butt wink, they instantly think it’s a horrible thing. But you need to ask when it occurs. If it only happens at the very bottom of the squat, it’s probably not as bad as most people think.

If it’s excessive and starts early in the descent, it could cause an injury down the road. If it’s right at the bottom and occurs in a person without a history of back pain, it’s probably not that big a deal.

Sometimes, we can’t change the amount of butt wink. It can be an anatomy issue where the femur only has so much range of motion in the acetabulum in the pelvis. (That’s basically a limited range of motion in the hip.) For that person, if that’s their only issue, it may mean that ass to grass squatting with a barbell on their back is not right for their body. In that case, I might recommend parallel squats or low bar back squats, which rarely go very far beyond parallel.

But sometimes, butt wink is an ankle mobility issue. If an athlete has very stiff ankles and they go into a deep squat, they’re going to hit their end range of ankle mobility early on in the descent and, in order to continue squatting deeper, their pelvis will have to move excessively as a compensation.

By improving ankle mobility and allowing the knees to translate further over the toes, theoretically, you can give your hips more time to maintain a neutral relationship with the lumbar spine. That’s why the first thing I check when an athlete experiences butt wink is their ankle mobility.

Remember, you should only squat as deep as you can with good technique. Technique is one hundred percent the most important part of any barbell training, especially squats.

BB: What’s the most frustrating myth you hear about squatting?

AH: Squatting deep is bad for your knees. Or, squatting causes knee arthritis.

Researchers have found that there’s no significant increase in the prevalence of arthritis in the knees among weightlifters and powerlifters compared to non-athletic people. Why? Because they don’t go heavy every single day.

If you have a good program that fluctuates in your intensity, sets and reps, and it allows your body to recover and heal itself between heavy workloads, then you’ll recover and improve on your previous levels of strength, mobility, and power in a healthy way.

BB: Cool. Anything else you’d like to add?

AH: Squatting is all about moving well first and then lifting heavy weight. And if you can learn to approach the barbell every time with the intent of doing a good rep, good things will happen.

This interview has been edited for space and clarity.

Images courtesy of Dr. Aaron Horschig.