If you have ever visited the USA Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, you will notice immediately that the facility is not a high end hotel. It is a conveniently located, one-stop shop for an athlete to train, recuperate, sleep, stay healthy, and improve their skills. During my recent trip to Uzbekistan for the 2016 Asian Weightlifting Championships, I had the opportunity to visit their Olympic Training Center (OTC). My first impression of the Uzbekistan OTC in Chirchiq, Tashkent Region of Uzbekistan, was that it was similar to their American counterparts, except the overall facility was much more …. basic. AND there were a lot more cows than in Colorado Springs.

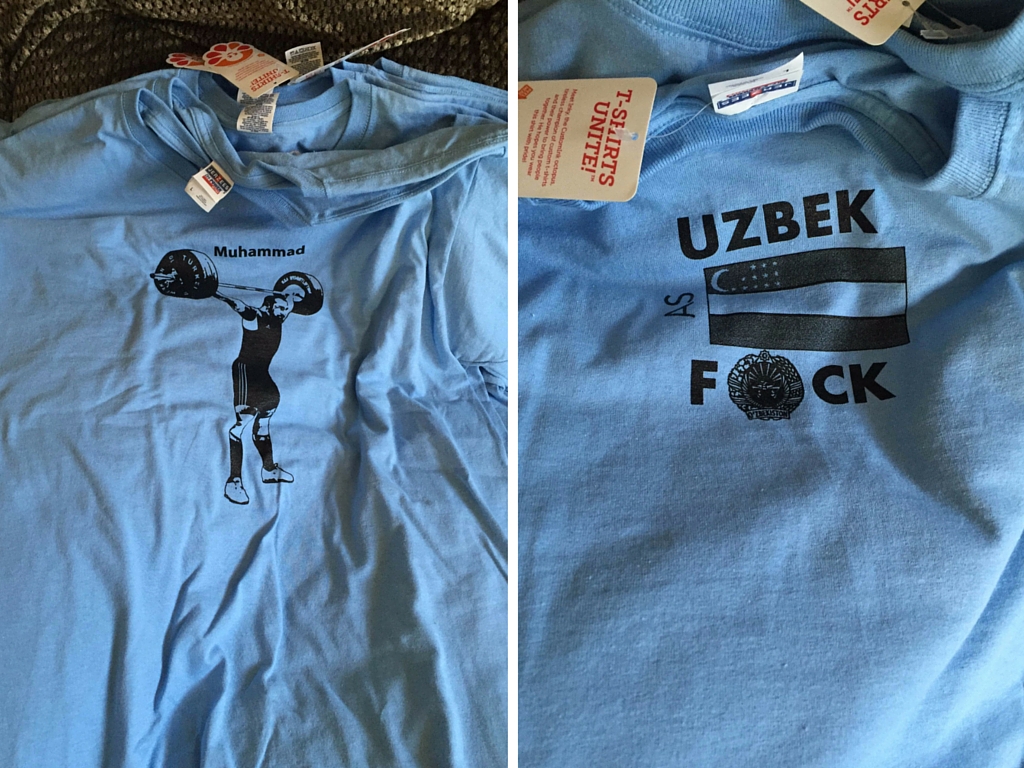

Monday, April 25th was my first full day in the country. I was notified by several members of the Uzbekistan National Weightlifting Team that they were having two training sessions that day (10AM and 5PM) and they wanted me come watch. In addition to being my friends and very friendly people, they knew I brought them tshirts from the United States – and everybody likes cool tshirts. I have been friends with several members of the Uzbekistan National team for several years, primarily through 85KG team member Muhammad Begaliev. Begaliev’s mother lives in New York City, and I have several times had the privilege of serving as his competition coach at local events. Additionally, I have met and befriended other team members who I have met at the Senior World Championships over the last several years.

At 3PM I took a 30 minute taxi ride from my hotel to the OTC. Chirchiq is definitely considered “farm country,” and I saw many people taking their cows for walks on a leash. My first stop was a dormitory where the athletes live. It resembles a college dorm, as all the athletes live in single or double occupancy rooms, with a larger shared common area. I was first greeted by Begaliev, since he is a student at Lindenwood University and is fluent in English. However, the rest of the team came by to say hello, each with various levels of English fluency (which were pretty much all better than my Russian or Uzbek). For example, Ruslan Nurudinov (105KG, 2013 World Champion) is basically fluent in English, while Ullubek Alimov (85KG, 2014 World Championships Silver Medalist) speaks only Uzbek and can understand Russian. However, they all enjoyed the tshirts I brought from the USA that featured Muhammad Begaliev’s picture.

After a tour of the dormitory area, we walked next door to the training center for the 5PM training session. It is a very basic facility, with platforms built into the floor and portable squat racks. There are no pictures of great Uzbek Weightlifters from the past or references to the Olympic Games. The only noticeable feature is a radio, which one of the athletes plugged their iPhone into so they could listen to rock music for the duration of training. It is worth noting that at 5PM sharp, Nurudinov said something in Russian, and they walked next door to the track and everyone (including myself) ran a lap around the track. While they do not do “cardio,” this is part of their warmup. They then did stretching on the track before walking back to the weight room to do their last heavy workout before the competition.

Ruslan Nurudinov helping a fellow lifter warm up

After training, I was invited to have dinner with most of the athletes. We went to a local restaurant that served the national dish of Uzbekistan: Plov. I had the privilege of riding along in Ruslan Nurudinov’s car. From what I’ve gathered, most people in the country do not have cars, and that holds true for the athletes as well. As a comparison, athletes in Russia who are Olympic Medalists or World Champions often receive luxury cars as part of their compensation (BMW, Lexus, or Audi). In comparison, Nurudinov has a very nice Toyota, which he received as compensation for winning the World Championships in 2013.

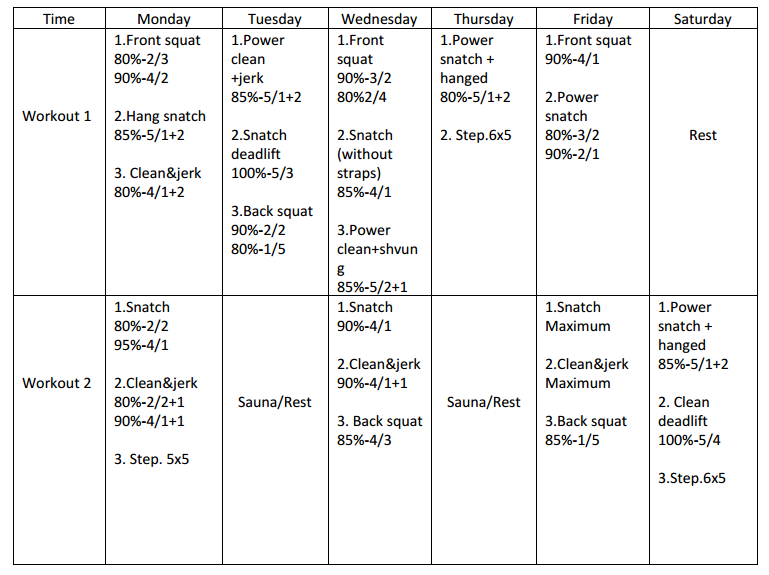

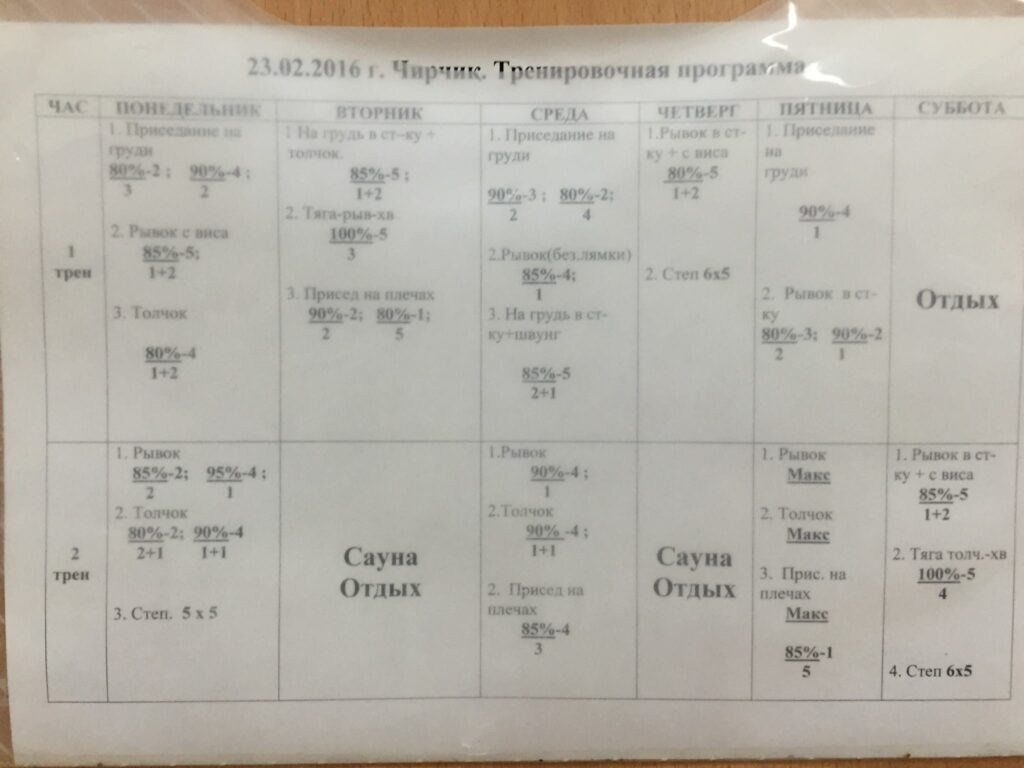

I was given an example week of the team’s training schedule leading up to the Asian Championships, which I’ve included below, along with a photo of the original Russian language version.

Note: On the training program, when it says, for example, 85% 5/1+2, that means 5 singles of power then 5 singles of full (i.e. power snatch and then full squat snatch).

In my limited interaction with the team, the quality of life of an athlete in Uzbekistan appears to be better than the average for the country — but to be fair, I’ve only seen a small fraction of what Uzbekistan has to offer, and it’s a remarkably large country. From an early age, the athletes start out in their home towns with a local coach, and as they progress they work their way toward the national team. Most have college degrees where they studied physical education, though in Uzbekistan I interpreted that as more broader than in America where most people think of a physical education (gym) teacher. Abroad, physical education would include topics such as Physical Therapy, Kinesiology, Anatomy, Physiology, and much more.

The author and Doston Yakubov (69KG), 8th at 2014 World Championships

Another fringe benefit of being an athlete in Uzbekistan is an opportunity to see the world. As an American, I take that for granted. I can use my credit card to buy an airplane ticket. The average person in Uzbekistan does not have credit cards or access to what Americans might consider normal banking. The currency is significantly devalued to the point where $1 U.S. is worth roughly three thousand units of Uzbek currency. A majority of the athletes I met had traveled to Houston, TX, in November for the World Championships and they enjoyed the food, the people they met, and their overall experience in the United States. Very few Uzbeks have ever — or maybe will ever get to — experience that, at least in the near future.

Life after weightlifting appears about the same; a few go into coaching, but that option appears to be based more on knowing the right people than anything else. I did not get the impression they receive pensions, so when their weightlifting career ends, the money ends as well. In that regards, it is the same as being an American weightlifter.

Editors note: This article is an op-ed. The views expressed herein are the authors and don’t necessarily reflect the views of BarBend. Claims, assertions, opinions, and quotes have been sourced exclusively by the author.