It is a hell of a time to be associated with youth weightlifting in America. In the preamble to CJ Cummings’ record breaking championship at this year’s Junior World Championships, Austin, Texas, played host to the USA Weightlifting Youth National Championships. And host they did, as 733 athletes competed over the three day event.

When the USA only qualifies 1 male for the 2nd straight Olympic Games, several thoughts hold merit: they need more athletes, younger athletes, and better athletes. For the longest time a majority of athletes (including myself) became involved in or after college when they were finished participating in a team sport. That is far too late, especially when you consider the rest of the world exposed their athletes to the sport during elementary school.

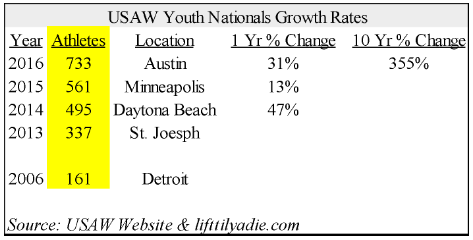

In the last few years we are seeing significant growth rates in the participation of younger athletes at the Youth National Championships. As the chart below shows, there was a +31% increase in the year over year athlete participation, and +355% in the past 10 years.

This is important because the first step in athlete development is to have athletes. Over the next 10 years, when these 733 athletes are in their prime lifting years of 21-27 years old, a lot of them will not be actively lifting. Attrition will come in the form of injury, lack of interest, work needs, family needs, pregnancy, marriage, or something else. Having a large number of athletes at a young age is a best practice that America needs to continue to support, because the best countries in the world maintain this practice and fully exploit it.

In conversation with Russian athlete Vasily Polovnikov and world renowned coach Yasha Kahn, they informed me that every year 50 or so kids, roughly 12 years of age, are invited to try out in the sport of weightlifting in Polovnikov’s small village. They are pushed, coached, worked very hard, and most leave the program for one reason or another. Those who stay turn out to be very successful. In his group of 50 athletes, it was himself and World Champion Khadzhimurat Akkaev.

Taking a look at the 2006 Youth National Championships: Five athletes developed into USA World Team Members at the senior level, which represents about 3% of those athletes.

- Jessica Lucero (63KGs, 2015 World Team) – Placed 3rd at 53KGs – Under 17 Yrs

- Jared Fleming (94KGS, 2011 & 2015 World Teams) – Placed 1st at 69KGs – Under 15 Yrs

- Michael Nackoul (85KGs, 2013 World Team) – Placed 2nd at 77KGs – Under 15 Yrs

- Spencer Moorman (105KG, 1st Alternate 2015 World Team) – Placed 1st at 94+KGS – Under 15 Yrs

- David Garcia (105KGs, 2013 World Team) – Placed 1st at 85KGs – Under 17 Yrs

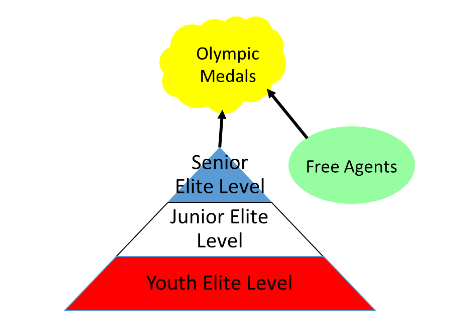

This is significant, because there are only two ways that a country can produce an Olympic or World Medalist at the senior level. One is through “free agency” – America could start to purchase elite level athletes from other countries and place them on their team. This has been done in the past by countries such as Qatar and Azerbaijan. The positive of this method is that there is almost no cost involved in developing the athletes. However in America, this school of thought is taboo and discussed in the same regards as Performance Enhancing Drugs (PEDs).

While it may appear that the USA has dabbled in this practice before, examples many bring up don’t exactly qualify. Geralee Vega was born in Puerto Rico and has been an American citizen since birth. Norik Vardanian has dual citizenship with Armenia, and received his American citizenship when he was a child who wanted to play basketball in southern California. Leo Hernandez received his citizenship in 2015, and that was after he went through the long and complex US citizenship process that took over five years to accomplish.

Right now, that leaves athlete development as our sole way to develop Olympic medalists. In the last five years, America has seen top youth athletes such as Jared Fleming and Ian Wilson have high levels of success and then suffer an injury that set them back. While injuries happen and are parts of sports, the lack of high level athletes meant there really wasn’t an answer to the question “Who’s next?” If CJ Cummings is the face of USA Weightlifting and he suffers an injury, who’s next to step up and keep the progress moving forward?

In my opinion, the USA Weightlifting leadership has done a great job under Michael Massik and Phil Andrews to grow the youth membership. They understand it is a pipeline to more competition and greater results at the junior and senior levels, nationally and internationally. At the 2016 Youth Nationals, it was great to see numerous states like California, Georgia, Minnesota, and Florida, represented by strong programs and leadership. It was equally gratifying to see athletes from states such as Nebraska, Idaho, and North Dakota which have had minimal weightlifting in the past, and are now bringing athletes to a national stage.

That being said, in a perfect world, the number of athletes needs to reach closer to 1,000 at the Youth Nationals (with roughly half that number of athletes at the Junior Nationals, University Nationals and American Open). The Senior Nationals should be under 400 athletes (or less) to show off the best of the best.

This will not be easy, as there is still an infrastructure issue of sufficient officials at these less sexy competitions. The Senior Nationals is the most important domestic event in the calendar year, and everyone and their mother will attend who is an official. The other four are arguably developmental national events – with lower weights being lifted by athletes who are not as developed yet. Hence less officials show up, and those who do show up need to more hours to make the event happen. USA Weightlifting needs better incentives for these officials because the officials are the lifeline of these competitions.

In February of this year, USAW announced there would be an annual calendar with 9 national events tentatively scheduled per year starting in 2017. Speaking as a nationally certified referee, I do not plan on attending more than one in the capacity of referee due to the amount of work I need to do compared to the compensation for that work. Maybe I will go as a reporter for BarBend, or as a coach, or maybe make a comeback and be a 56KG athlete again. But it is hard for me to want to take vacation time to spend a weekend officiating and paying almost full price for hotel and airfare when USAW had a net revenue increase of over $230,000 in their most recent IRS Form 990 (which shows 2014 vs 2013). In Canada, officials have their trips paid for in full by the provincial associations.

If USAW wants to maintain a true volunteer organization, then link officiating at the smaller national events to participating as an official at the bigger, sexier national events. For example, when allowing sign ups for the 2017 Senior Nationals, let the officials who have worked at the previous four national events have first choice in which sessions they work. Then officials who were at three national events, and so on. If I knew I could referee or announce or be the marshall for the star studded 94KG or 77KG weight classes, that would entice me to show up at more national events throughout the year.

Regardless, thanks to exposure from CrossFit and money, there are more athletes at all ages coming to national events. That is great, but we need to be able to support this. When Pedro Meloni, the new events manager of USAW arrives here after the Olympics, I wish him luck in figuring this all out and continuing on the promising path forward Phil Andrews started.

Editors note: This article is an op-ed. The views expressed herein are the authors and don’t necessarily reflect the views of BarBend. Claims, assertions, opinions, and quotes have been sourced exclusively by the author.