Event 11 of the 2016 CrossFit Games will be a walk to the finish line. Specifically, a handstand walk to the finish line.

According to Castro’s surprisingly specific post (which likely means there will be some twist involved), the event consists of a 280 foot handstand walk for time. The specificity of “280 feet” has lead some to believe that there will be an additional 5000 feet of exercise thrown in for Event 10, so the two events combined will round out to a nice 5280 feet, or one mile.

Though handstand walks have been a staple at the Regional and Games level since 2014, we’re always surprised at the number of athletes who struggle. For many, inverted walking is not a natural movement, but most are strong enough to chug through. We see this in everyday athletes as well. Many are comfortable holding a handstand against a wall, but ask them to walk, and it does not compute.

Despite the plethora of tutorials and progressions found on the internet, that there is one cue that is often overlooked: hand placement. For athletes who have the strength to hold themselves upside down, aren’t scared to be upside down, but still can’t get the hang of walking, we find that altering hand placement solves more handstand walking issues than any other quick fix. The cue is simple and subtle: rotate your hands outward so your thumbs are facing forward and your fingers are facing sideways.

For some athletes, slightly rotating the hands is intrinsic. They just do it, and never have to think about it. They’re usually the “naturals.” For others, it’s something to think about until it becomes ingrained. So, why does this fix help?

If we go back to handstand progressions, people are generally taught to get comfortable in the pushup position first, and then eventually that position translates to a handstand. In a pushup position, the fingers face forward, and so goes for handstand progressions against the wall and later, for freestanding balancing. When athletes begin to learn to walk, coaches most often tell them to feel like they’re “falling” and to “catch themselves” in order to get the feeling of walking. Handstand walking and handstand holding are two different things, though, so telling athletes to just “fall” without addressing mechanical differences in hand placement immediately sets them up for failure and frustration.

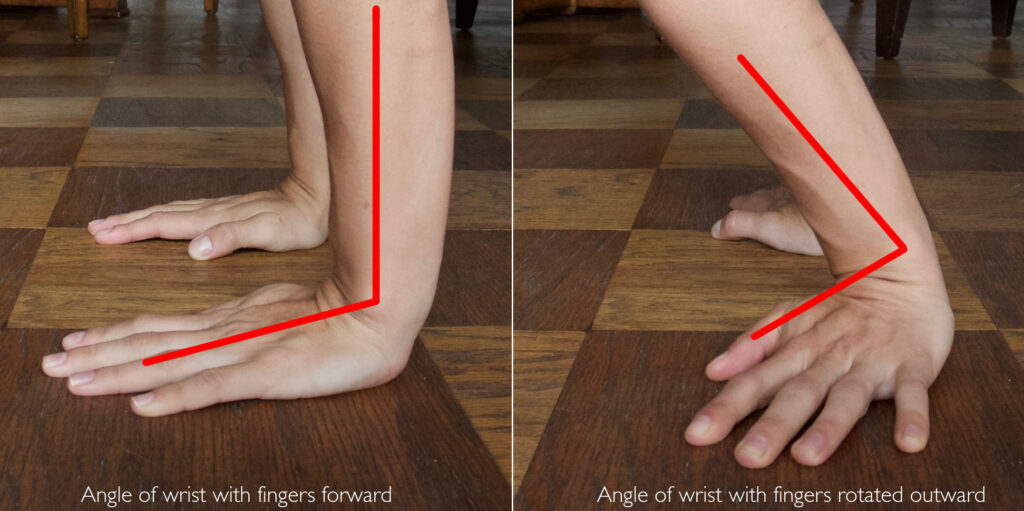

In holding vs. walking, the hands and wrists function differently — in a handstand hold, the hands and wrists are there to stabilize and balance. They don’t need to move, so you want them in the most stable position, which is fingers facing forward, the forearm stacked at a perpendicular angle to the palm of the hand. In a handstand walk, the hands and wrists are helping the body move through space, so we need to optimize range of motion. Fingers facing forward suddenly presents a problem because not only are they are literally in the way, but the wrist joint itself hits its limitation.

Experiment with this theory by getting on your hands and knees with your fingers facing forward. Rock back and forth, keeping palms flat on the ground, and notice how there ‘s a limit to the angle of your wrist joint. Now, rotate your hands outward, approximately 30 degrees, so your thumbs are facing forward. Notice how the range of motion increases. If you’re handstand walking, you want the freedom to take steps without reaching your joints’ limitations. Getting your fingers out of the way helps too, it’s basically the difference between walking in clown shoes and walking in shoes that fit.

This all goes back to “falling.” In order to walk effectively, the athlete has to “fall” so his/her bodyweight shifts in front of the hands. The body goes first, and the hands catch up. If the angle between the palms and the forearm is greater than 90 degrees, the body is by definition, behind the hands and can’t “fall” properly. You can’t walk if the body isn’t “falling” in the right direction.

This is where athletes who are strong enough can muscle their way through a handstand walk. They bend their knees and elbows and contort their bodies into scorpion like bends so enough of their weight is moving in the right direction. It’s killer on the back and fatigues the shoulders. Even Castro’s model, Dan Bailey, looks like he’s precariously Frankensteining along the football field.

It’s only when the angle between the palm and the forearm is less than 90 degrees that the body shifts over the hands, allowing it to “fall” so the athlete can walk. As soon as the athlete realizes this difference, it’s all about faith and muscle endurance over brute strength.

Here’s a great example. On the left, the male athlete’s fingers are facing forward. He’s clearly got the strength to grit through, but he’s got work much harder to physically “step” over his fingers every time, which means he’s sort of teetering back and forth on each hand instead of going through is range of motion. His legs are flailing to balance out, and he has to lift his hands a few inches off the floor in order to move.

On the right, the girl has her fingers rotated slightly outward and is therefore able to move through her range of motion. She’s much more stable, and looks like she’s walking as opposed to teetering, and only has to lift her hands an inch or so in order to move forward.

As we said, this is a simple and subtle change, but when it comes to handstand walking, it’s the little things that make all the difference.