If you want to be an astronaut, you don’t just need a science background and a thousand hours of pilot time in a jet aircraft—you need to train legs.

BarBend was lucky enough to sit down with U.S. Air Force Colonel and NASA astronaut Mike Hopkins to discuss his love of back squats, how he completed “Murph” in orbit, and why he thinks functional fitness will help us get to Mars.

Editorial Note: NASA would like to make it clear that as a government employee, Colonel Hopkins is not officially endorsing CrossFit, Inc. or any commercial product in any way.

BarBend: Colonel Hopkins, thank you so much for taking the time to talk.

Colonel Hopkins: It’s great to talk to you.

BB: So, you’re a colonel in the U.S. Air Force and a NASA astronaut, and you spent how long on the International Space Station?

CH: I spent 166 days on board the International Space Station, from September 2013 through March of 2014.

Colonel Hopkins awaits a spacewalk training session near NASA’s Johnson Center in Houston. Image courtesy of NASA.

BB: I’ve read that you grew up on a farm and that fitness has always been important to you. Recreationally, you’re a fan of CrossFit® training, is that right?

CH: Yeah, I’ve been physically active in sports pretty much my entire life, from playing football, basketball, doing track all the way through junior high and high school. I played football at the University of Illinois and once I got out of college and was commissioned into the Air Force, it just became one of those things where you develop a routine and working out and staying fit becomes a part of your daily life.

What’s been nice is that once I came here to NASA, fitness became a very critical part of being an astronaut, and there’s an annual fitness test that we have to pass to be eligible.

So, NASA does these kind of Workout of the Day-type activities, where you’re doing a combination of things that can include Olympic lifting, powerlifting, bodyweight exercises, and a lot of those things, similar to what you might see in CrossFit. But if someone wants to go to their own gym or their own box and work out there, we don’t stop them.

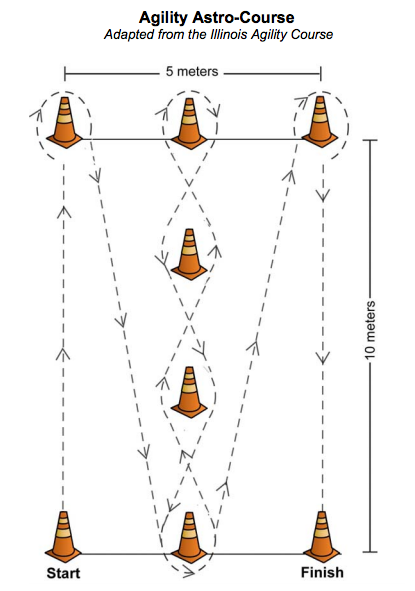

NASA’s standard agility training course – don’t knock over any cones. Full description here, image courtesy of NASA.

BB: What are the benchmarks someone has to pass in the annual fitness test?

CH: One of the things we do is a max VO2 test, where they put you on a bike with the tube in your mouth and you go to failure as they continue to increase the load.

The other ones are more simple things like push-ups and sit-ups and pull-ups. We also do grip strength, which is important because during space walks, when you’re out in the suit and pressurized, your grip strength is important to manipulate tools.

They’ll also do an evaluation of your agility, which is important because when you spend time in a microgravity environment your inner ear can get messed up, and when you return to Earth, balance and agility activities can be difficult. So we want to have a baseline.

BB: How many push-ups do you need to do to qualify as an astronaut?

CH: That’s a good question, I don’t know what the mins are. I just tend to push myself as hard as I can, and no one’s ever come to me and said you aren’t passing!

BB: What do you like about functional fitness, as far as its carry over to what you need to be able to do in space?

CH: One of the nice things about a CrossFit®-type workout is you’re able to get a lot in, in terms of exercising different parts of your body and different functions in one workout.

You get some of that anaerobic work as well as the strength exercises, and if you can do all that in a half hour instead of having you lift weights for half an hour, then go run for half an hour, then go do something else, I think there’s a lot of value in that. Our schedules here can be quite challenging, so that’s a way we can pack a lot in in a shorter timeframe.

Image courtesy of NASA.

I also just enjoy the variety that comes with CrossFit-type workouts, how the workouts change daily versus programs where every week you’re you’re squatting reps of five or four or whatever it is. I think there’s value in those as well, but I’m a type of person who enjoys the variety.

BB: You mentioned earlier that NASA programs Olympic lifting and powerlifting in their WODs, is that considered important for space travel?

CH: Absolutely. But we don’t do things like snatches and power cleans very much, we’ll usually do squats and deadlifts and things like that.

That’s because when we’re in orbit, we have a machine up there that allows us to lift weights, but we can’t really do things like a snatch. But it works very well for powerlifting movements.

Colonel Hopkins walks through the machine that lets him do WODs in space, the Advanced Resistive Exercise Device (ARED).

The reason strength is so important is in the microgravity environment, it’s easier for muscles to atrophy because you’re not really using them, you know? When you walk in from your car to your work, you’re using your muscles. In space, we don’t ever have to do that.

But not only do our muscles atrophy, we can lose up to two and a half percent of our bone density every month. So, loading up the bones is critical to help counteract that. And the areas where you often see a lot of bone loss is in the hip and the pelvis, so having the squats and the deadlifts – where you’re really loading those areas – is absolutely huge to help prevent that.

BB: Because you could argue that it’s more important to exercise in space than on Earth, do you need to exercise more often than the average person? What’s the periodization look like?

CH: What’s awesome is that in space, and this is absolutely fantastic, you have two to two and a half hours dedicated to working out every day. This is because of the risks associated with the muscle atrophy and bone loss and things of that nature. So, we have that on our calendar.

Colonel Hopkins enjoys a Thanksgiving dinner in space. Image courtesy of NASA.

One of the bad parts about being in space is you’re separated from your family and friends and all these other things we tend to do with our free time down here. But the advantage is, you don’t have a lot of those kinds of distractions, and so it’s very easy to jump in and get your workouts in and all of that. For that six-month period when I was in orbit, I worked out every single day, except for two days when I went out on spacewalks.

So it was great. I probably came back in the best shape I’ve ever been in.

BB: Do you find the body recovers more easily in space? I mean, two hours a day, that’s a lot.

CH: Yeah, actually, you do tend to recover much more quickly. You know how down here, if you haven’t done a squat in a while, the next two days can be pretty tough, right? Your legs are really sore and it’s just painful. In space, no, you didn’t see that.

BB: Because recovery is just recovery, you’re barely using the muscles at all.

CH: Yeah. And even if you were to pull a muscle, or tweak a back, or something like that up there, you tended to be able to recover in days versus weeks, which it might take you here on the ground.

BB: So you Lifted Heavy Every Day?

CH: We have three devices on station: a weightlifting device, a treadmill and an exercise bike. The weight training device we tend to have on people’s schedules every day. A lot of people might take a day off and that’s OK, but I like to work out, so I used to do it every day.

The treadmill and the exercise bike I would alternate, but don’t think of the treadmill as just an aerobic type exercise — it also loads the bones. When we’re on the treadmill, we wear a harness and bungee our way down onto the treadmill. It’s very challenging, because if I want to run at my bodyweight in space, I have to load up those bungees so that they’re pulling down on me at 185 pounds. That means I’m carrying 185 pounds on my shoulders and on my hips.

BB: It feels heavier than running at bodyweight on Earth?

CH: Yeah, it feels different. When I run on Earth, I don’t have any of that pain in my shoulders or hips. That became challenging with the treadmill. But it’s also very effective.

NASA astronaut Steve Swanson running on the treadmill, a.k.a. the Combined Operational Load Bearing External Resistance Treadmill (COLBERT). Image courtesy of NASA.

BB: Tell me about the weight training device, the Advanced Resistive Exercise Device (ARED). Can you do just about every lift with that thing?

CH: Well, squats are a primary lift for us and we’ll vary it, we’ll do a normal squat, we’ll do a sumo squat, you can also do a front squat with it as well.

You can do deadlifts, and we’ll vary that as well. We’ll do a normal deadlift, sumo deadlift, you can do bench press, you can do shoulder press, you can do thrusters. We’ve got a cable on it so you can do front raises, curls, heel raises.

Colonel Hopkins completes Angie, a popular CrossFit® workout.

BB: It even works calves?

CH: Yeah. What’s interesting is, I was involved in an experiment where you measure your body dimensions, and I saw some significant losses in terms of my calf size within the first couple of months.

BB: Because you’re not walking.

CH: Yes. So, I actually adjusted my heel raise workouts to do lighter weights but more workouts.

BB: Yeah, calves need a lot of volume.

CH: Exactly. Some of the things we can’t do though are like the power cleans, the snatches, but that’s OK. We don’t really need to do those.

BB: Did you manage to do a Crossfit® WOD up there at all?

CH: I did do some, but with the ARED, you have to set it up for each individual lift, right? So I would do Murph for example, where you run the mile, you do the 100 pull-ups, 200 push-ups, 300 air squats, and run a mile.

The problem there is when I do Murph, I want to do the sets of 10-20-30 or 5-10-15, right? Well, it takes time to switch between doing push-ups because I can’t really do push-ups, so I do a bench press. Pull-ups I can’t really do, but I did a bent-over row. And the squats, I would put 160 pounds on the bar for simulating an air squat. But again, you just aren’t as quick because you’re constantly having to reconfigure the weight on the ARED.

Colonel Hopkins crushes a Murph.

But that’s the kind of thing I’d do on a Sunday, bodyweight workouts. During the week I’d be doing heavy squats, heavy deadlifts, sumo, single leg squats. Single leg squats are great up there, because it’s very easy to stay balanced and you can do absolutely beautiful single leg squats in orbit.

BB: What do you mean by bodyweight workouts, though?

CH: Well, when I say bodyweight work I’m doing something equivalent. Instead of doing a push-up, I do a bench, but I put the weight at 135 pounds to simulate a push-up, because when you do a push-up you’re not actually pushing your full weight because of the way you’re oriented.

And to simulate doing an air squat, I wouldn’t use my full bodyweight because as you do an air squat here on Earth, you’re not lifting your lower legs or anything like that. So I would do something like 160 pounds.

BB: Is your fluid intake the same?

CH: Yeah, on a day-to-day basis, we’re trying to have the same intake of calories and fluids as we have down here on Earth.

NASA Astronaut Dan Burbank doing space deadlifts. Image courtesy of NASA.

BB: Did you do any other well-known CrossFit® workouts in space?

CH: I did quite a few different ones. I did a Fran.

BB: You did a Fran?! What was your space Fran time?

CH: (laughing) I can’t remember. I have it recorded. I think I videoed the whole thing, but I don’t know where it ended up. But again, it’s much longer because of the reconfiguration of the device.

BB: I need that video.

CH: I think it’s on YouTube somewhere.

BB: It’s not!

CH: Oh, well.

Colonel Hopkins’ famous selfie, taken on Christmas Eve 2013. Image courtesy of NASA.

BB: You said CrossFit is useful because it also increases your VO2 max – why is that important?

CH: That’s just part of your overall conditioning. I don’t have any data that supports this, but I do believe that being conditioned in multiple ways— for instance, having good aerobic conditioning and having good strength conditioning — is important. Having good VO2 max helps you in all the other types of exercise you do. I think it helps with your recovery times and anything else you might be using as your exercise.

If we were to stay in space, you wouldn’t have to work out because it wouldn’t matter if your bones got weaker. A big reason we do the exercises on board is because we wanna come home! (laughs) And when you come home you want to be able to function.

It’s also important as we look at long duration exploration, right? I mean, we – NASA, the United States, the human race – we want to go from Earth to a place like Mars. And getting to Mars is gonna take you months, so if you spend six months in a microgravity environment getting to Mars and you finally land on another planet, you want to be able to actually go out and explore that planet. And if you haven’t kept your body in shape, you’re not gonna be able to do that when you get there. So, functional fitness is also important to just being able to do the job when we look at exploration.

Image courtesy of NASA.

BB: Last question: What are your PRs?

CH: My best power clean would have been when I was in college, that would have been 325 pounds. My best squat was 405, 415, something like that. And we didn’t do deadlifting in college, but before I launched into space I was doing 365 pounds for reps of five.

BB: Awesome. Anything else you’d like to add?

CH: Working out and staying physically fit is something that’s very near and dear to me, so I enjoy the opportunity to be able to share that story, and what it’s like, and the challenges that are associated with having to try and do that in space.

BB: Great! I can’t thank you enough for your time.

CH: You bet. You too.

This interview has been edited for space and clarity.

All images courtesy of NASA. BarBend would like to thank Colonel Mike Hopkins, NASA’s Public Affairs Officer Brandi Dean, and the entire National Aeronautics and Space Administration for their help putting this piece together.

You can see more of NASA’s fitness and workouts on their Facebook page, Train Like an Astronaut.