It is one thing to study war

And another to live the warrior’s life

–Telamon of Arcadia, 5th century B.C. Mercenary

Chose an individual sport; any one of them:

- Triathlon?

- Singles sculling?

- Wrestling?

- Sport fighting?

- Strongman?

All are quite different in the demands placed on the athlete and the skill set they require. While you can argue that you need great equipment, periodized training, a nutrition protocol, recovery plan, natural ability, and a great coach, I contend that those all help but aren’t necessary. Sure, the best typically have those at their disposal, but is that what makes them great? I think not.

At the core lies a common denominator for elite success that eventually determines the best: The ability of the athlete to suffer. Often this must be done alone and without validation for long periods of low intensity or short bursts of excruciating self-induced torment.

It is human nature to seek comfort and avoid that which we find uncomfortable. Our society (in my case, American society) has been developed to keep us safe, warm, and well nourished. There is very little voluntary behavior that we ever do that is not either benign or pleasurable. Think about it. Very few people mow their lawn, paint their house, move their furniture, or anything that makes us suffer in any physical way. This way of life is quite detrimental for the athlete, for enduring the stress required to train to be the best is learned behavior — and it starts in youth.

My first organized competitive sports experience was summer track in the fifth grade. Coach Dave Johnson (DJ for short) would meet up with a bunch of kids from 5th through 8th grade and coach track events (and try to get us to be better human beings). After six weeks of training, this would culminate in a county wide meet where we got to show off our speed and power.

We would start every practice with running laps. One, two, three, it often depended on the heat, but we always got our heart rates up. After a little stretching we would break up into age groups and with the help of his high-school student assistants, go over proper technique in sprints, hurdles, high jump, and a few other things little kids can handle. I got to run a few different events back then, but the longest we had was the 400. I hated it. It’s an all out sprint for about a minute and change depending on how old you are. So every year I ran the 400 and never did all that well at it because you just suffered the whole time. Most kids hate suffering. I did it anyway, didn’t complain but was grateful when it was over.

I took my youth track status with me to Clarence High School. It has a deep and long record of excellence. I was part of that team, but not the excellence. However, I got a great free education there, and the excellence did start to rub off on me. When you are around really great athletes you see the qualities in them that you lack. I knew I wasn’t a really great runner. My nickname on the team was the lumberjack. I was just bigger in the shoulders than most of the team and would have been much better suited to throwing, but I ran my whole life, so I kept running.

I got stuck running the 800. It’s a horrible event and most people that run it hate it. It’s two and a half minutes (for the average kid) of pain. Dennis Webster was an older teammate of mine who also ran the 800 and still holds his 1988 record time of 1:50. At the time this was only 8 seconds over the world record. This was mind blowing to me as kid who slogged across the finish line in 2:33.

Dennis was older, taller, leaner, and built for running, but so were the guys he was beating, often by 10 seconds in races. One day after a training run, I asked him why he was killing these times. He said something to the effect that at the point when it hurts and everyone either maintains pace and endures, he speeds up and goes into the next level of discomfort.

This obviously makes sense in theory, but implementation is a different animal. I took his advice and started implementing it during my training runs. Every time I wanted to slow down, I’d speed up for as long as I could. When I felt that I absolutely had to slow, I would do so only to the previously set pace. I quickly adapted to this at 16 and closed out my Junior and final track season running a 2:17 in the 800!

This struck a chord with me. I could get better at something if I was willing to be more uncomfortable longer than the next guy. This thinking became my mantra in my Senior year when I quit playing school sports and started full time training in the gym. I could differentiate myself by always getting that extra rep, by doing every second of my pre planned cardio; negatives, drop sets, supersets, giant sets, sprints, the list was endless. If you got OK with not being OK you were going to starting beating the average guy because he doesn’t have that mindset.

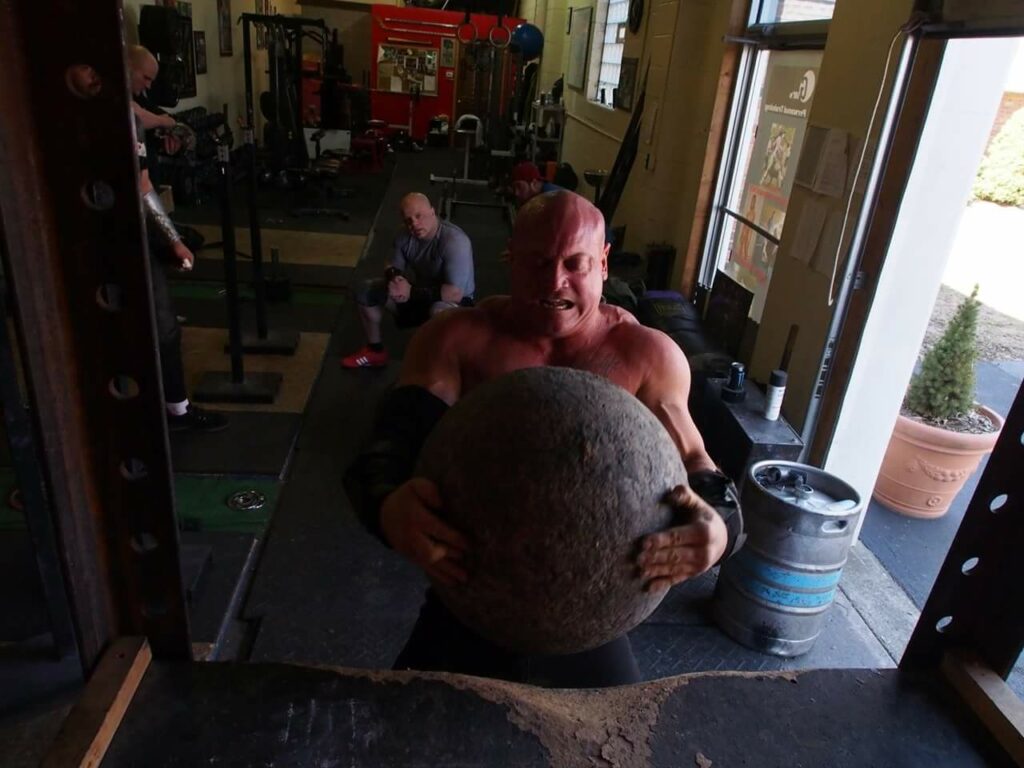

This, my friends, is what is required in Strongman (training and contests); the will to keep going when everyone stops. It’s the secret that everyone knows and very few discuss because we all feel we do this already, but in practice? Only you really know the redline and very few ever see it. So many competitors quit rep events early because they think they physically can’t do any more.

They are wrong.

They just don’t want to do any more.

It is so easy to put a look of pain on your face and set the keg down and walk away. It is ten times harder to keep walking and go until your legs buckle and the keg hits the ground on its own. While that may only be five more seconds of work, it can seem like five minutes of torture.

Working a heavy clean & press for reps is a test of technique and mental fortitude. The guy hitting perfect rhythmic reps every six seconds is going to be able to get to the deep pain zone and make the winning press over the athlete who is sloppy and going to settle for five. Are you going until the timekeeper blows the whistle? Or do you hear 10 seconds left and walk away?

Are you hitting your limits for real? Do you:

- Do timed sled races for conditioning with your crew and try to win?

- Enjoy the challenge of trying to do a bodyweight stone for 10 reps in 30 seconds?

- Work in front carries and do them on limited rest?

- Try and move faster at the end of log clean and press for time during training?

- Give your best efforts only on singles and doubles and kind of sit out the rep work?

The quote that starts this article speaks volumes as to who is actually invested in their future. It is easy to tell everyone you meet that you are a Strongman and how you pull trucks and load stones. If you seek their attention it is all the validation as an athlete you need. Only you know the absolute truth to how deep you dig and what you are willing to endure.

But the true path of the individual athlete calls for you to suffer, and no outside validation can compensate for that. It’s deeper meaning lies only in your expectations of yourself and what you are willing to accept.

Editors note: This article is an op-ed. The views expressed herein are the authors and don’t necessarily reflect the views of BarBend. Claims, assertions, opinions, and quotes have been sourced exclusively by the author.

Featured image: @strongmancorporation on Instagram