If you were to track my nutrition through my athletic career, you’d likely see a pretty big series of peaks and valleys. I was a college soccer player, downing everything that could roughly be classified as a “carb” in order to power grueling games and endurance training. Then I found CrossFit as a skinny kid in my late teens, and my focus shift toward putting on weight and getting as big and strong as the athletes I looked up to. (That’s still a work in progress.)

Annual beach seasons, though, created some periods of rather “intense” cleanliness in my diet — or at least what I then perceived as eating clean.

But as I’ve grown as a functional fitness competitor — and this year, finally a CrossFit Games athlete — my perspective on eating has become gradually more refined. Food has become less of an afterthought — gone are the days of mindless scarfing — and more of a means to an athletic end.

More and more athletes dial in their nutrition, and these days, they’re asking for help. I sat down with Renaissance Periodization founder Nick Shaw to talk about perceptions of nutrition in strength sports, and ultimately how the differing demands of each influence what athletes need to make progress.

Disclaimer: As an athlete, I’ve received support and nutritional advice from Nick Shaw and his team.

Nick Shaw

1. How did you start Renaissance Periodization (RP)? Why?

Shaw: Super simple answer: We (Dr. Mike Israetel & myself) were tired of seeing folks using “broscience” or using myths, fads, and gimmicks to sell stuff in the fitness industry. We knew that science would help us get to the truth and that was our goal all along. We wanted a staff that could combine academics AND athletics (not just one or the other). Why have just one? When you can have both.

2. Do you think athletes still underestimate the connection between nutrition and performance? Is it possible to OVERestimate the connection?

Yes, I do think athletes at the very highest levels tend to underestimate the importance of nutrition. A lot of the VERY best athletes in the strength sports world (especially in their younger years) skate by on genetics and talent alone. What I’ve noticed is that those same athletes as they start to get more years under their belt start to realize the importance that nutrition can have on proper recovery and on more productive workouts overall.

I’ve also noticed that females (on average) tend to pay closer to their diets, especially at the higher levels than their male counterparts.

I think it is possible to OVERestimate the importance in some cases. If athletes are aiming for diet PERFECTION year round, it will eventually cause them to burn out. Diet is certainly important, but trying to be a robot and be 100% on point is almost impossible (even for the highest level bodybuilders, they still take an off-season). What that perfection ALL the time tends to cause is folks to just completely fall off the wagon at some point and then it’s tough to get back on. Knowing that it’s likely a bit more important to pay attention in the months leading up to a big meet than right after can be a helpful tool to help athletes relax a bit and enjoy themselves.

Nick Shaw

3. Can you explain how the nutritional demands of these sports vary, in your experience?

Weightlifting – Weightlifting tends to be longer sessions, so you can easily make the argument that the peri-workout nutrition is more integral than some other strength sports. If you’re a higher level weightlifter in the gym for 3 hours or more and NOT supplementing with an intra workout shake, you could really be missing out on some performance benefits. The longer you train, the more your workouts can take a hit at the end and proper nutrition can help fix that. We have seen that time and time again at RP for folks going from consuming next to nothing around training to supplementing properly.

Functional Fitness – This is a tricky one! A lot of times CrossFitters are notorious for some of the hardest and most BRUTAL workouts you can imagine, but at the same time they’re so intense that the TOTAL training volume doesn’t compare to some other strength sports. This causes folks to miss the mark a bit as they confuse training INTENSITY with training VOLUME. Carb intake is highly dependent on overall training volume, not intensity, so although a CrossFitter might have busted their ass in an hour class, they still don’t need a ton of carbs compared to say a weightlifter in the gym for 2 hours or so doing tons of sets (thus more overall volume).

My good friend and top CrossFit coach Jacob Tsypkin said it best:

“The important thing to remember is that the ratings of “light, moderate, hard (in reference to the RP diet templates)” are not measurements of exertion, but measurements of training volume. A three minute CrossFit workout can feel very, very hard, but it doesn’t do much in the way of depleting substrates and it doesn’t cost a whole lot of calories. Look at the amount of work you’re doing, not the way it feels.”

Powerlifting – Powerlifting tends to be pretty similar to weightlifting in terms of the way we think about it, but the phases will vary for carb intake. For example, when you’re peaking for a powerlifting meet you’re hopefully not doing as much volume as you would when in a hypertrophy block. Thus, in the hypertrophy block, you’re likely eating more carbs than the other phases. Obviously there are exceptions to the rule, but that’s a pretty good starting point.

Strongman – Again, should be somewhat similar to powerlifting/weightlifting, but the big thing here to plan around is for the actual event training. Typically, these workouts can be 3-4 hours (if not longer) and that requires some special tweaks. One might be increasing your carb intake pre workout to help account for the longer sessions and another might be splitting your intra shake into two parts to help get in more total fluids over the really long sessions.

4. Does performance have an appearance?

I think a big thing for strength sports is being able to fill out your weight class (if your sport has them) with as much muscle as you can without giving up performance. This typically means being at the very top end of your weight class with maybe 10% body fat or so for males and 15% or so for females. This means you’ll be packing about as much muscle as you can for your class and with more muscle usually means more strength.

Image Courtesy RP Strength

With a sport like CrossFit, there are no weight classes, but if you can have more muscle and less fat, chances are that will make you better! So long as you’re not getting so lean (think stage ready for physique competitions) that it impacts your performance, getting leaner is a great idea to get better at CrossFit.

5. What’s been your biggest obstacle since RP started?

Overcoming the countless myths, fads, and gimmicks that are seemingly everywhere in the fitness industry. Anybody out there that has abs and is popular can lend their advice and to me that just seems silly. That’s why Dr. Israetel and I sought out to have the smartest folks we could find and I think at our latest count we have 11 PhDs on staff here at RP (including several Registered Dietitians and a practicing Medical Doctor).

If you wanted Medical Advice, you wouldn’t just go to somebody that happened to be healthy, you’d seek out the credentials to go along with that. For some reason that same line of thinking doesn’t apply to the fitness industry. A set of abs somehow is as powerful as a boatload of degrees/certifications and that seems to be a bit off. Obviously looking the part plays a role, but why not have both!

6. What’s one piece of advice you would give to athletes who struggle with diet?

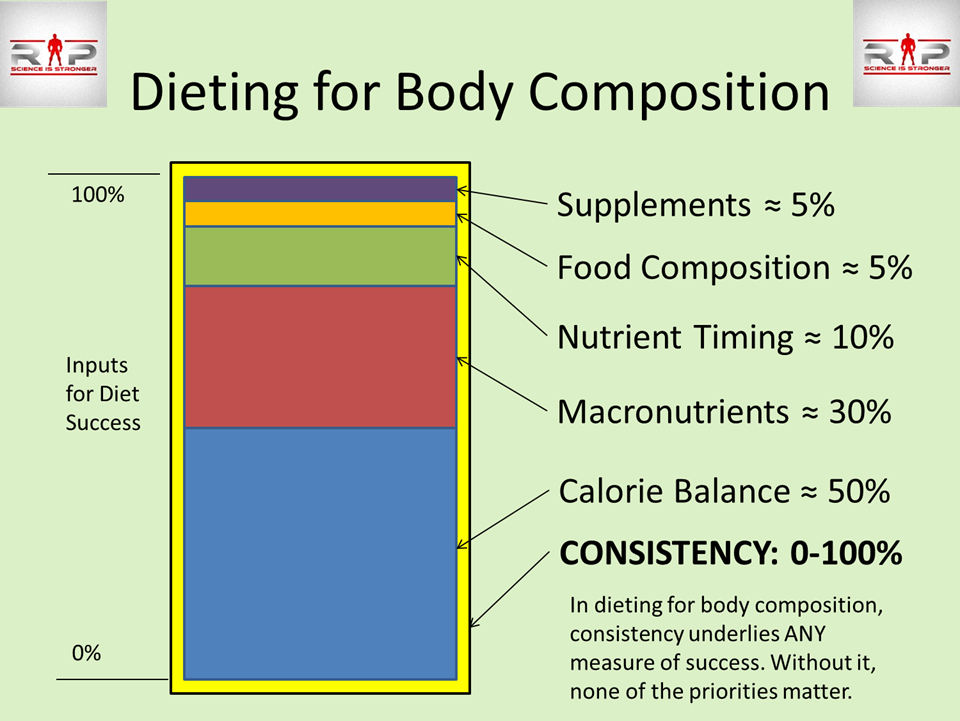

Realize that even the greatest diet in the world doesn’t mean much without consistency. This means learning to be flexible in your approach here and there to help with long term results is crucial. If you know the nutritional priorities (image below), you can tweak things to help fit your particular needs and be able to have a smart and sustainable diet for years!