You did it: you took the journey and brought your friends and family along – you competed in a powerlifting meet. Leading up to it, you posted training video after training video on social media, snapped picture after picture of your meals, and wrote note after note about how great you felt in the gym and how you were going to crush some personal records in your contest. Except, there’s one problem: when game day arrived, you stepped onto that platform and failed.

What went wrong?

All too commonly, good athletes do poorly in competition, and oftentimes, their failures are avoidable. Here are some reasons why.

Editor’s note: This article is an op-ed. The views expressed herein and in the video are the author’s and don’t necessarily reflect the views of BarBend. Claims, assertions, opinions, and quotes have been sourced exclusively by the author.

Practice Like You Play

In a sense, competition should not be special. Each attempt should, essentially, be just a routine lift. For most powerlifters, even striving for a personal record on a third attempt should still generally be a natural and reasonably routine progression to a logical new level.

Yet, all too often, competitors treat meets as though they are something different from their regular training. Unsurprisingly, this often leads to failure. Indeed, if an athlete treats a contest as something different from training, then what is it that the athlete has trained towards? And, why should an athlete then expect to excel at that contest if it is something other than what he has trained for?

Here are some basic ways to train for competition:

Strive to make every single rep in training perfect.

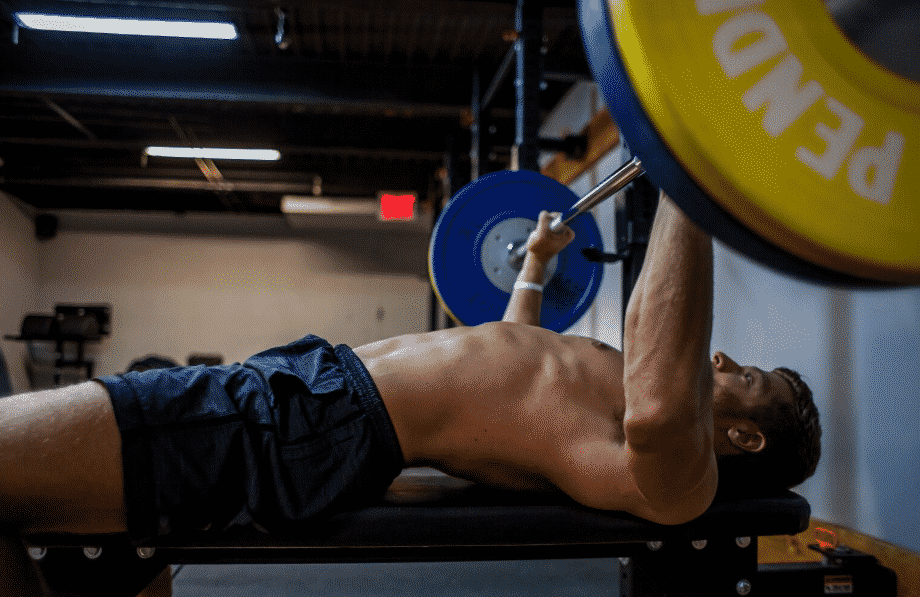

It is a mistake to train with poor technique but think that it will be possible to just “step it up” on game day. Laziness in the weight room translates into failure on the platform, so make sure to fight for position under every load in training and execute each and every squat, bench and deadlift according to competition standards. For example, make a habit of squatting to depth, use proper bench pauses in the gym, and properly lock out deadlifts every single time you break that barbell off the ground.

Don’t rely too heavily on training aids.

The majority of powerlifters likely train in commercial gyms, with subpar equipment: slippery benches and basically bald and often bent barbells. Wearing a grip shirt or wrapping a bench in resistance bands is tempting in order to avoid slipping while bench pressing, and the idea of using lifting straps can be quite attractive when trying to pull a deadlift on a barbell that feels as smooth as a PVC pipe.

However, if grip shirts and lifting straps are not allowed in competition (and federations such as the USAPL do not permit them), then a lifter who relies on these aids will likely experience a carryover problem on the platform. Although competition benches are tackier and competition barbells do have knurling that resembles cheese graters, competition benches simply do not offer the same amount of traction as a grip shirt and the aggressive knurling just does not connect a lifter to the bar in the way that wrapping a pair of lifting straps around it will.

Make an effort to find a gym with competition equipment and get in some training there.

People who train 100% of the time at a commercial gym can have a rude awaking on the platform, when they need to lift competition bars loaded with calibrated kilo discs. The problem? Competition bars are extremely stiff. Also, kilo plates are razor thin and therefore keep the load closer to the center of the bar, minimizing the competition bar’s already negligible amount of bend. Competition bars, covered in sharp knurling and loaded with kilo plates are merciless, and this can throw off some lifters, especially on deadlifts. Indeed, if someone has only ever worked with flimsy commercial gym barbells which bend just at the thought of them, then it can be rather unsettling to grip an aggressive powerlifting bar for the first time on the platform.

Think about that moment in Rocky IV when Apollo (RIP) touched gloves with Drago at the beginning of the fight by slamming his fists on top of Drago’s, but the Soviet’s gloves didn’t move at all. A competition barbell is the same way – often an unyielding Swedish import that looks you in the eye and says, “I must break you.” Don’t let it.

Practice heavy singles with competition commands.

Learn the commands, find a friend to bark them at you, and then just do it. One’s perception of time changes under a heavy load. You might think that you’ve paused that bench on your chest for three minutes, but to the outside world, it’s barely been a nanosecond. Also, jumping a start or a rack command is painful. It’s important to train yourself to listen to commands even while you have a crushing amount of weight sitting on you.

Don’t face the mirror during squats and deadlifts.

In competition, powerlifters don’t get to watch their form in mirrors. Instead, they stare at a head judge against the backdrop of an audience. If one gets accustomed to looking in a mirror while squatting or deadlifting, then removing the mirror is almost like putting on a blindfold – it negatively impacts a lifter’s balance and it does not bode well for game day. One needs to develop the ability to feel that his form is correct, rather than rely on visual queues during the movement. Besides, who wants to look at himself while performing the Valsalva maneuver anyway.

Back to the broader reasons you keep failing in meets.

Warming Up Too Much

Save it for the platform. Dial down the volume and intensity in the warm-up area, and hit just enough reps and weight in order to prepare yourself to handily execute your opener. Confusing a warm-up with a workout often leads to bad results. A lifter should be as fresh and as ready as possible when he first sets foot onto a platform, not pre-fatigued. Just remember: there’s no grinders in the Warm Up Room. NONE!

[Keep reading: 5 last-minute things to remember on meet day.]

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bbi3Q0XDQ4P/

Poor Programming

Peaking is both an art and a science. The general idea though, is to lower volume in order to let fatigue dissipate, while increasing intensity in order to prepare the body to handle competition loads and fine tune competition skills. These elements need to be balanced against excessively lowering the volume which could result in too much physical deconditioning, and also balanced against excessively increasing loads to the point where pre-game recovery efforts are rendered unsuccessful.

Assuming that the athlete went through a training macrocycle in which he gained lean mass via a hypertrophy phase and then trained the additional muscle in a subsequent strength phase, a properly planned peak will be necessary. Also, if you have a good program, stick to it. Don’t just attempt a personal record at any time in the gym. It risks disrupting the entire training cycle and in turn having a negative impact on one’s performance in competition.

Poor Game Day Nutrition

Nutrition is a complex universe unto itself, so at the risk of oversimplifying matters, let’s keep it very basic: on game day, eat familiar foods that are high in sugar and low in fat. Consuming foods that are high on the glycemic index will help provide the quick energy needed to effectively execute attempts. Fat delays digestion, so eating foods that are high in fat slow and therefore undermine the quick energy effect that one wants to obtain.(1) Personally, I sip on Gatorade mixed with whey protein, while munching on fat free Fig Newtons as needed while I’m competing. Food is a tool during competition. Save the tasty meal for your post-meet celebration.

[Learn more: 8 IPF Powerlifting Champions Share Their Pre-Meet Meals]

Stage Fright

Lifting in front of a set of judges and an audience can induce more anxiety than getting underneath the weight itself. This is why training is so important. An athlete who trains correctly can let the training take over, and it will. The nerves can actually function to produce adrenaline, which can in fact prove very helpful, particularly when stepping up to one’s third attempt. Control the nerves, don’t let them control you. Naturally, this is easier said than done, but repeated exposure to competition conditions will help over time.

[Keep reading: How to find a routine and control your mind on competition days.]

Poor Attempt Selection

The best is often the enemy of the good. Save personal record attempts and podium runs for third attempts. Openers are for getting on the board and building a total. Make sure you have a good idea of how to pick your lift attempts on meet day.

Wrapping It Up

Game day is about execution, not excuses. Train specifically for the task at hand, use good judgment while warming-up and fueling, and step onto the platform rested and clear-headed. Remember, a powerlifter’s job is to lift the most weight and perform best where it counts – on the platform.

Reference

1. Dr. Mike Israetel, Dr. Jen Case & Dr. James Hoffman, The Renaissance Diet: A Scientific Approach to Getting Leaner and Building Muscle, Renaissance Periodization, 2016.