How many times have you gotten towards the middle or end of a long training cycle, only to realize that you’re feeling tired, achy, and frustrated by slowing progress? And — assuming you stuck with the program — how many times have you then, seemingly out of the blue, nailed an awesome workout?

If you’re relatively new to powerlifting, this phenomenon can seem inexplicable. Common sense tells us that if your body is getting worn down, you’re going to be incapable of performing at the same level you would be if you were fresh. Unfortunately, the body isn’t that straightforward.

The Ins and Outs of Progress

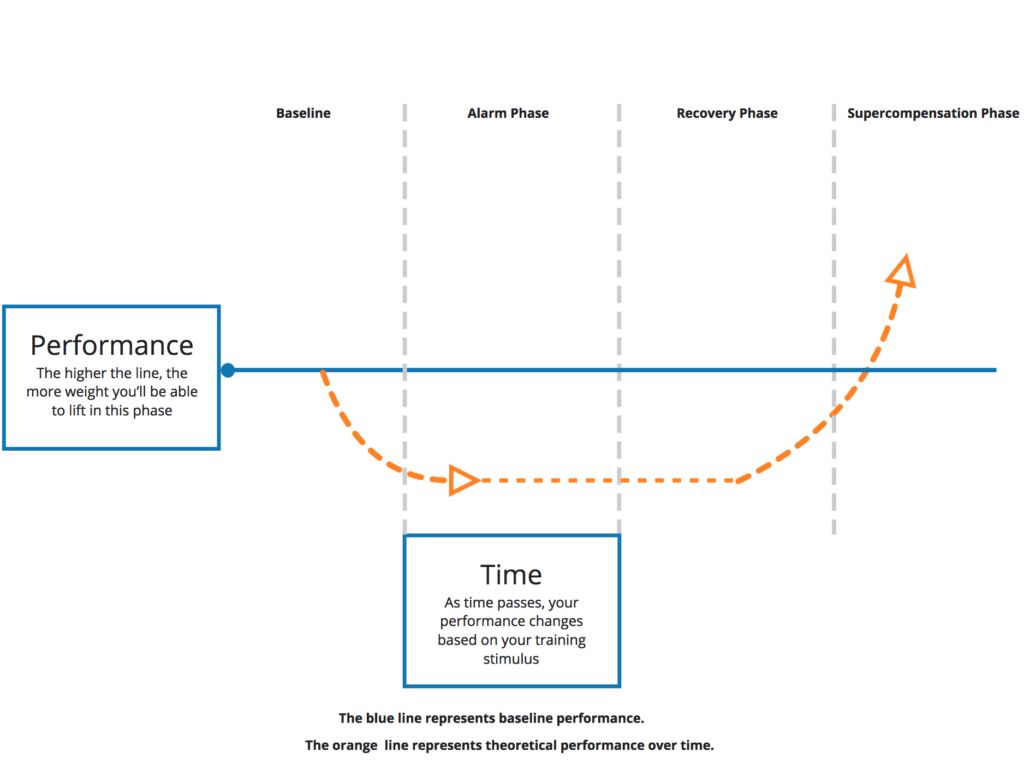

See, when you train, your body freaks out a little — you end up sore and tired. That’s called a stress response, and, if you don’t give your body time to rest and heal, then the next time you go to train, your performance will probably suffer. But if you do give your body time to rest and heal, then your body supercompensates, and you come back stronger.

(If you train again after the supercompensation phase, the process repeats. Otherwise you detrain. If you don’t rest or don’t train again after supercompensation, you get weaker — shown on the right side of the chart below.)

This whole processes is known as General Adaptation Syndrome, and it was theorized by a researcher named Hans Selye and later applied by Russian sports scientists with great success.

In theory, the whole process looks something like this:

Of course, in practice, nothing is that straightforward. So while we can use the GAS to understand stress at a high level, we need to be a little more nuanced when we’re concerned with our own training.

What Progress Looks Like in Practice

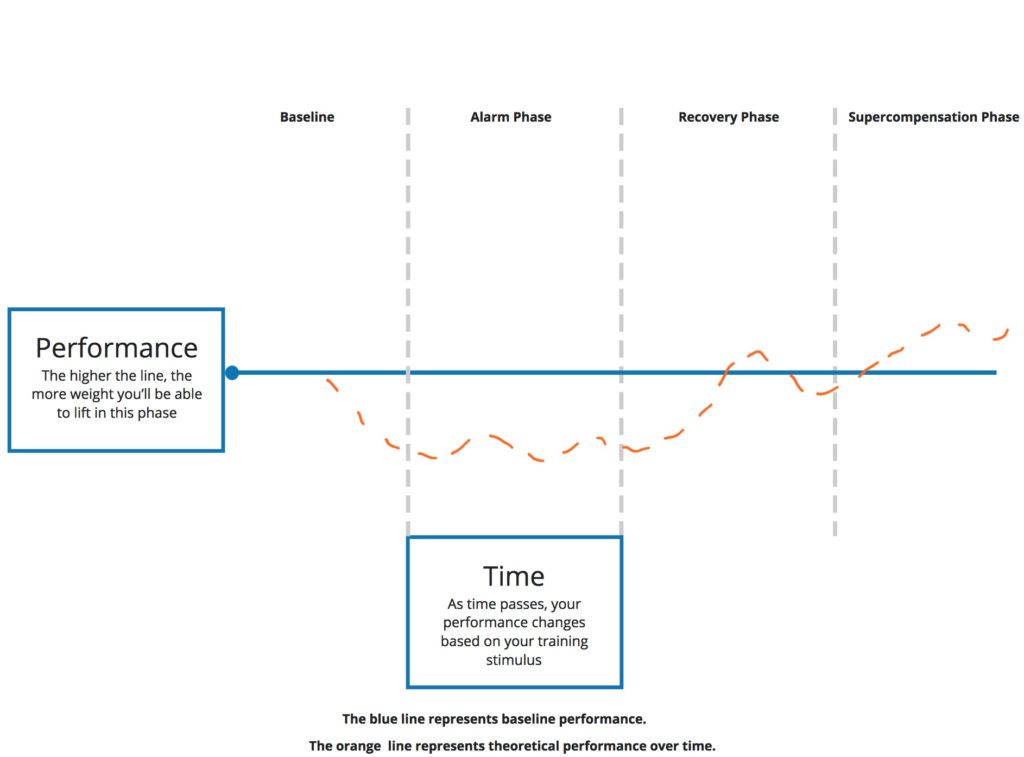

Instead of a nice, clean chart like the one above, imagine that your stress response instead looked something like this:

The “wavy” line reflects the fact that stress isn’t all that simple. For instance, take the stress of training: how can you compare the difficulty of a set of max-effort block pulls to a set of squats with 90% 1-RM? Clearly, they affect your body very differently, but it’s not clear how to quantify that difference.

It’s the same with stresses outside the gym: lack of sleep, poor nutrition, and relationship or career problems all create a stress response, but not necessarily a uniform one, and that response can vary from day-to-day or even hour-to-hour.

The result of all this:

It’s much, much more difficult to predict how your body is going to perform on any given day than you might like it to be.

How to Use This Information for Progress

It’s not all bad, because once you understand that, you can at least make more informed decisions. One very common method is the use of RPE-based loading, which you can learn more about here:

Personally, I struggle when using RPEs alone to program, so I take a different approach. Here are there ways I use the idea of stress and stress responses to help get stronger.

1. When planning training cycles.

Personally, I’m a huge fan of waved loading, which simply refers to intentionally varied stress levels from week-to-week. This helps me physically, by incorporating periods of planned “over recovery” into my long-term strategy. It also helps mentally, because if I start to feel run down, I know that I have a lighter week coming up soon and that I don’t have to push through tough workouts indefinitely.

If you want to see an example of waved loading in action, check out my free offseason program (which you can read more about by clicking here).

2. When deciding whether to deload.

Deloads can be really tricky — not least of all because powerlifters rarely like to deload. In addition, if you’ve experienced the “great workout when run down” phenomenon I described above, then even when you “know” you need to deload, it can be very tempting to push through anyway, in hopes of hitting that awesome session despite not feeling too great.

However, if you’re charting your progress over long periods of time, then you can learn to recognize dips in performance and what they likely mean for the future. And, if you understand the GAS, you can have the confidence to know that if you do deload, then you’ll come back stronger.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Btgv9molIfA/

3. When you have a bad workout.

Conversely, if you have just one bad day in the gym after a string of great sessions, you can recognize that as a dip caused by those little fluctuations in stress and your body’s stress response. Hopefully, that makes it easier to stick to your plan, and not program hopping just because you had a bad day.

Wrapping Up

What strategies do you use to deal with those periods of slower progress? Share them in the comments below!

Editor’s note: This article is an op-ed. The views expressed herein and in the video are the author’s and don’t necessarily reflect the views of BarBend. Claims, assertions, opinions, and quotes have been sourced exclusively by the author.

Feature image from @phdeadlift Instagram page.