At my first powerlifting competition, I bombed.

This means that I wasn’t able to complete at least one attempt of either the squat, bench press, or deadlift. In my case, it was the bench press, which was my strongest lift based on training. As might be expected, there are a lot of factors that go into performing well at your first powerlifting competition that extends beyond the training process.

In this article, I share 15 steps that any powerlifter should know when competing for the first time. These are the things that I wish I knew going into my first meet, and the factors that helped me go on to become a national champion and world bench press medalist.

The 15 steps are:

- Go to the competition venue one day prior

- Have a game day coach or handler

- Don’t cut weight

- Practice the movement standards

- Read the rulebook

- Get the proper lifting attire and equipment

- Be realistic with what you can lift on meet day

- Take the 100% shots with your attempts

- Bring any warm-up modality that you need

- Think about your food choices ahead of time

- Ask a lot of questions to those around you

- View the first meet as the ‘first of many’

- Learn from your missed lifts

- Start a post-competition journal

- Get involved in ‘non-athlete’ roles

1. Go to the Competition Venue One Day Prior

If you’ve never been to the competition venue before, then you should visit one day prior to your meet day. The idea is that you want to develop a mental map of the space that you’ll be lifting in ahead of time.

Here are the things you should be looking for:

- Where will the competition platform be? Get a sense of what the room looks like from the vantage point of the competition platform. This will help you understand, for example, where you’ll be looking in the squat, where the chief referee will be sitting, and where you will enter and exit the platform when it’s your turn to lift.

- Where will the warm-up room be? You’ll want to find out if the warm-up room is in close proximity to where you’ll be competing or if it’s far away (i.e. in another room or on another level). This knowledge will allow you to gauge the timing of your warm-ups so that you take into account the time it will take to walk from the warm-up room to the competition area.

- Where will the weigh-ins be? From my experience, the weigh-ins rooms are not in obvious locations. Sometimes they are in washrooms, sometimes they are behind makeshift curtains. You don’t want to show up on meet day searching for the weigh-in area, so make sure to know where the weigh-ins are located.

- Where are the washrooms? For obvious reasons, you’ll want to know where the washrooms are located in proximity to the competition area in case you need to go in between attempts. This will be a good gauge of how much time you have to budget for yourself.

My advice: Get familiar with the competition venue beforehand so that you know where you need to be at different points throughout the day.

2. Get a Game Day Coach

A game day coach is someone who manages all aspects of your meet day, which will drastically reduce the amount of stress that you will experience at your first competition.

Background

In the sport of powerlifting, there are two kinds of coaching roles:

- A personal coach who writes your programs and assists with your technique.

- A game day coach who handles all aspects of your meet day from warm-up management to attempt selection.

For most, these two coaching roles will be the same person. However, this is not always the case.

Let me explain further…

Some athletes’ personal coaches aren’t located in the same city, which is common in the online coaching model. As such, these coaches aren’t able to travel to the competition and act as a game day coach. For example, I’m located in Canada and I coach several athletes in the US. While in the past I have traveled to National level meets to coach my athletes, I have not traveled to every local or State competition that my athletes compete.

In these cases where I’m not present, we have arranged a ‘game day coach’. If you’re in a similar situation, where you don’t have a game day coach, you should arrange one to work with you at your first competition.

The Importance of a Game Day Coach

At a powerlifting competition, there are an infinite amount of little things that can distract you from your job as an athlete, which is to lift as much weight as possible.

For example, there are rules that you must follow from how much time you have to submit your next attempt to the increments you can select. There is a ‘timing to the day’ where you must be in certain places at certain intervals. There are technical standards that might cause you to miss a lift and not know why. There are both written and unwritten rules and protocols about how to behave in the warm-up room and staging areas.

All of these things can cause you stress.

But, with a game day coach at your side, you don’t have to worry about any of that. You can focus on lifting weights and nothing else.

Can your ‘friend’ or ‘significant other’ be a game day coach?

If your friend or significant other has relevant powerlifting experience, is a coach by trade or has competed before, then they would be a good candidate for a game day coach. However, if they don’t, you should look to hire a game day coach that has the skills and knowledge to help you succeed. You want someone who knows the sport rules, understands how a powerlifting competition runs, and can explain all the protocols of meet day to you.

Where to find a game day coach?

If you don’t know where to start in hiring a game day coach, you should reach out to the meet director and ask if there are any game day coaches they can refer you to. You could also get connected with other athletes through social media ahead of time and ask them who their game day coach is. If you have a coach who designs your programming, often times they will know a game day coach in the powerlifting community who may be able to attend the competition with you.

My advice: don’t do your first competition alone. Look into getting a game day coach ahead of time.

3. Don’t cut weight

In order to reduce as much external stress as possible, you should not cut weight for your first competition, even if that means being less competitive in a higher weight class.

Background and Problem

Powerlifting is a sport of weight classes. You will compete in a weight class and be ranked based on these categories. The higher the weight class, the more weight you will be expected to lift.

From my experience, first-time powerlifters who are a few kilos above a specific weight class are more inclined to lift in the lower category. They will do any number of things to cut weight, including restricting calories for weeks leading up to the competition, water loading, and sweating in a sauna the day of the meet.

/ Shutterstock

This approach to your first competition is not advised for several reasons:

- At a local competition, you will probably be the only one in your weight class or one of very few. What this means is that the classes are not very deep at this level. Therefore, you’re almost guaranteed a medal regardless of what weight class you compete in.

- Even if the higher bodyweight class is more competitive than the lower bodyweight class, your goal for the first competition should not be centered on ‘being competitive’. You should be focused on making all your attempts, learning the sport rules, and become comfortable in the competition environment.

- As it is, there will be a lot of external stress on meet day. This is because you’re entering a new environment, and for the first time, you’ll be lifting in front of three referees and an audience. Adding in a weight cut to your competition prep will only contribute to the amount of stress you’ll already experience.

My advice: Don’t stress yourself out with last-minute water loading protocols or sweat sessions in the sauna. Focus on having productive workouts leading up to the competition and fueling those workouts with an appropriate nutrition plan.

4. Practice the movement standards

Each of the movements will have technical standards that you must follow in a competition. You need to understand what these standards are, and then practice them in training.

Background

I have a saying:

“Your worst rep in training, will be your best rep in a competition.”

What this means is that if you’re not consistent in training with the movement standards, then you can’t expect it to come together in competition. If you expect that your worst rep in training will be the rep that you do in competition, then it will force you to be more consistent and lift to the appropriate standards.

When you’re going for a max lift in a competition, movement is unconscious and reflexive. You’re not thinking about each individual joint angle or muscle action. You’re focused on the ‘total movement’ and applying as much force as possible. As a result, your movement patterns will already be ingrained by the competition and based solely on the technique you practiced in training.

Common mistakes first-time powerlifters have with the movement standards:

- Not practicing the commands. You can’t start or end the movements without getting a command from the head referee. It’s not natural to lift under someone else’s command, so often lifters will jump the ‘start’ or ‘rack’ command. Even if you successfully complete the lift, it won’t pass. So, it’s important to practice these commands with your coach or training partners several weeks leading into the competition so that it becomes second nature.

- Not knowing where proper depth is in the squat. It takes some practice to understand where your hips are in space, especially under a heavy load. You might have the proper mobility, and be strong enough to perform deep squats, but if you’re not consistent with getting depth as the weight gets heavier then you risk not passing a lift in competition. For your first competition, you should go deeper than what’s required, just so you don’t have to worry about the judges calling you on missing depth. As you become more experienced and develop better body awareness, you can practice cutting your depth right at the threshold. If you struggle to get to depth, you can read my 9 tips to squatting deeper.

- Having poor habits that superficially make you lift more weight. In training, it’s easy to cheat yourself because you’re not being judged. As such, first-time powerlifters will often pick up poor technical habits because it allows them to lift more weight. These could be things like not pausing long enough on your chest in bench press or hitching on the deadlift. While these habits might let you lift more weight in the training environment, it will only set you up for disappointment come the competition. You need to put your ego aside on cheating the technique to lift more weight, and only consider the reps using the movement standards as your baseline for strength.

My advice: Practice how you want to compete. You can learn more about the squat standards, bench standards, and deadlift standards in these articles.

5. Read the Rulebook

You should be prepared on meet day with an understanding of the basic rules of the sport – this goes beyond what I discussed above regarding the movement standards.

Background

There are certain rules you must follow, everything from how the weigh-in process is conducted, how you submit attempts, what equipment you can wear, and how the lifting roster is structured. You don’t need to know every line item of each rule, but you should have a broad understanding of the ‘do’s’ and ‘don’ts’.

It always surprises me how many athletes show up to a competition and don’t know the basic rules.

/ Shutterstock

This would be like playing a board game with your family and not knowing how to advance in the game, or what you can or cannot do under certain game conditions. Your family might get pretty angry if you’re always breaking the rules, especially the most basic ones that everyone should know. The same goes for an athlete competing in powerlifting.

For example, a rule that you can expect in most powerlifting federations is that you only have a specific amount of time to submit your next attempt. Under the International Powerlifting Federation (IPF) rules, it’s a 60-second time limit. Therefore, if you’re taking too much time deliberating on what your next attempt should be as you finish a lift, you risk having your attempt not being registered or automatically going up by 2.5kg. This could be detrimental to your overall performance if you intended to go up by 10kg. This is only one of the common rules you should know by reading the rulebook.

My advice: read the rulebook of your powerlifting federation before you compete.

6. Get the Proper Lifting Attire and Equipment

Each powerlifting federation will have a specific list of lifting attire and equipment that you can and cannot wear. You should check to see that all of your lifting attire and equipment that you train with meet these standards.

Background

Just like any other sport, the federation will dictate what athletes can or cannot wear while competing. There are two reasons for this:

- The federation wants to have a standard for everyone that creates a level playing field. Certain pieces of equipment might be considered ‘performance enhancing’. Therefore, the federation will want to say that either ‘everyone can wear that piece of equipment’ or ‘no one can wear it’.

- The federation gets paid by corporate sponsors to have their logo represented in the competition environment. Typically, this means that brands must pay a fee to have their logo worn by athletes. Any company that doesn’t pay the sponsor fee, doesn’t get the branding rights.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BvPl_AnAy4a/

In powerlifting, it’s common to have equipment rules around the belt, singlet, shoes, knee sleeves, and wrist wraps. The referees will want to make sure that (1) they conform to a certain specification so that no one is being advantaged over another, and (2) that they are manufactured by one of the ‘approved brands’ who paid the sponsor fee.

With respect to the ‘approved brands’, the complicated part for an athlete is that the logos you can or cannot wear change at different levels of competition (local, state, national, or international). So it’s important to read the rulebook, and if you’re still unsure, ask the meet director ahead of time. Furthermore, you’ll want to check all the rules around the clothes you can or cannot wear in competition. For example, in some powerlifting federations there are rules around the fabric your t-shirt can be. In the IPF, a shirt can be polyester, cotton, a combination of polyester and cotton, but not spandex.

My advice: Start thinking about your ‘lifting kit’ ahead of time. Check your federation’s rules and ask the meet director when in doubt. All of your equipment will be checked by the referee at the weigh-ins, so be prepared to show your gear.

7. Be realistic with what you can lift on meet day

When you’re setting goals for your competition attempts, be realistic in what you can lift. Don’t select attempts based on an arbitrary ‘milestones’ or what you ‘want to do’. Rather, consider your training timeline and use evidence from your workouts of what you can lift in competition. This might seem simple, but implementing this point is rather hard. So, let me explain further.

Background

At some point before the competition, you will likely think about the goal numbers that you want to reach on your third attempts. The third attempt are the culmination of your training efforts. In essence, you train to make your third attempts. It’s the most amount of weight that you can lift on game day.

When thinking about your third attempt numbers, you should consider two factors:

- What is your timeline?

Athletes love to think about the weight they might be able to lift when they’re starting a new training cycle. They will set a goal weight for their third attempts several weeks, and sometimes months, out from the meet. For example, an athlete might deadlift 335lbs today, and have a third attempt goal of lifting 405lbs.

This practice of long-term goal setting in and of itself is not necessarily bad. However, I often find a disconnect between what the athlete wants to lift and the timeline they are dealing with. In the scenario above, if an athlete has 12-weeks to prepare for a competition, then going from a 335lbs to 405lbs deadlift may not be achievable. This is not to say it’s impossible, but the results would certainly not be typical, and it might involve training that is high-risk and not sustainable.

You need to understand a realistic rate of progression based on the timeline given. Even with the best programming and all conditions being perfect, ask yourself:

Is a 70lb increase in your deadlift in a 12-week time period realistic?

To understand this further, you should always breakdown your long-term goals into short-term milestones. In other words, if you want to increase your deadlift 70lbs in 12-weeks, how much would you need to deadlift after 4-weeks to be on track with this goal? In our example, it means you would need to increase your deadlift 23lbs every month for three months in a row.

An important principle to understand is that strength has diminishing returns…

The amount of time, energy, and effort that you must invest to continue seeing a net gain in strength increases the longer you train, which is why progress is not linear. You cannot expect to gain the same amount of weight month-after-month. So while you might gain 23lbs in the first month, you would have to spend more time, energy, and effort to increase at the same rate the following month. This is why elite powerlifters are happy only gaining 5-10lbs on their lifts every year.

My advice: Consider your timeline and rate of progression when setting your 3rd attempt numbers for the competition.

- What is your recent training evidence?

It’s important to analyze your training and use it as evidence for what your max capacity might be on meet day. Your competition numbers should not be based on what you ‘want to do’. Everything should be grounded in your training efforts, and you should place a higher value on the workouts that involve heavier protocols, such as reps between 1-3 at 85-100+% of your one rep max.

A good practice would be to record all of your lifts above a specific percentage (85%) on video and start creating a database of how you perform under heavier loads.

What you’re trying to understand is where your strength is on average, and then base your goal numbers at the meet off these averages. This is an important concept to understand. Let’s take a look at an example. If you complete 10 workouts: one workout might be the worst workout of your life, one workout might be the best workout of your life, and the other eight workouts are somewhere in between those two spectrums.

It’s clear that you would not base your 3rd attempts off of the worst workout of your life. But, would you base your 3rd attempts off of the best workout of your life?

Many people do.

However, I think it’s unrealistic to expect that the best workout of your life is a representation of what you can successfully put together on meet day, especially for your first competition.

There is a difference between one’s all-time ‘strength potential’ and ‘actual potential’ in competition.

Your ‘strength potential’ would be what you’re capable of lifting under the perfect conditions when all ‘stars are aligned’ on a given day. Your ‘actual potential’ is the strength that you can successfully transfer from the training to the competitive environment under real-world circumstances and the dynamics of the sport.

For example, you might have had the best workout of your life when all aspects of your day were controlled perfectly — sleep, nutrition, social interactions, time of day, rest intervals between warm-up sets, equipment used, familiarity with the gym environment, and so on and so forth.

However, for the first-time powerlifter, many of those variables that you can control in the training environment are not under your control on meet day. You also have the added stress of lifting in front of an audience, being judged by referees, and being governed by a whole set of new rules. Therefore, when you’re evaluating your training evidence to determine what might be possible on your 3rd attempt, you should look somewhere closer to the average of your strength in training – not the best or worst day.

Practically speaking, this might look like reviewing the five times you deadlifted over 90% in training and trying to understand how it moved on average. You might have one workout where it moved lightning fast, one workout where it moved like an absolute grinder, and three workouts where it moved smooth but hard. Based on that information, you can estimate what your 3rd attempts might be on any given day.

My advice: At your first meet, if you can simply transfer your top training numbers into the competition environment that would be considered a success. Over time, you could expect to exceed your training numbers in competition, but it requires you to grasp the skill of competing and getting used to lifting in that environment first.

8. Take the 100% Shots With Your Attempts

Once you’ve developed a plan for your attempts, you want to make sure that the numbers you actually select on meet day are ones that you are 100% confident in lifting successfully.

Background and Problem

Many lifters fall prey to two mental traps on meet day:

- They don’t adapt the original game plan. Once the game plan is set beforehand, they have a hard time going off that game plan. They ignore meet day conditions that might affect their strength.

- They lift with ego. Athletes put a weight on the bar that they ‘want to do’ versus what they think they’re actually capable of doing. This could be blindly going for a PR or milestone. They might even know that they’re not going to make the lift, but they want to ‘die trying’.

If you are selecting attempts in competition and know there’s a very small chance of lifting them successfully, then you risk:

- Wasting energy for future attempts. This is especially the case if you miss your third squat on strength — your deadlift strength will likely be affected.

- Losing kilos on your total. Every kilo that you can extract from each individual lift will add to your overall powerlifting total. A lot of newer lifters don’t prioritize the total, but it’s the total that ranks you in the sport, and allows you to qualify for higher levels of competition. Athletes who make more attempts will have a higher total than those who don’t. You can see from the data below that the male and female winners of every weight class at the IPF World Powerlifting Championships from 2012-2017 makes more lifts than the average lifter.

- Putting yourself in harm’s way. Anytime you put a weight on the bar that is impossible to lift, you increase the risk of injury. This is not to say that every time you fail you’ll get injured. But, it certainly increases the probability if you take those kinds of attempts frequently.

Strategies for picking successful attempts

While there are many strategies for picking attempts, the two most relevant strategies for your first competition are:

- Plan your attempts in ‘ranges’ not ‘singular numbers’. What this means is planning your attempts with a range of possibilities depending on a best case, average case, and mediocre case. For example, on average you might be able to deadlift 185kg for your 3rd attempt. But, the best case if you’re feeling excellent might be 187.5, and the mediocre case if you’re feeling less than ideal might be 182.5kg. When you design your game plan with ranges, then it’s much easier to deviate up or down in the moment because you’ll still believe it’s “part of the plan”.

- Use the prior attempt in competition as evidence of how you’re performing. Each attempt that you take on meet day will give you greater clarity on what your next lift will look and feel like. Your last warm-up will be a precursor to your opener. Your opener will be a precursor to your second attempt. Your second attempt will be a precursor to your third attempt. Every step along the way you should be evaluating whether or not you’re on track with your next attempt based on how you performed on the previous. At this point, it’s important to ignore how the weights felt in training, and strictly focus on meet day conditions and performance of your lifts. You should view your attempts as a compass for what to do next. If you’re performing better than expected, go to the high numbers in your attempt selection range. If you’re performing less than expected, go to the lower numbers in your attempt selection range.

My advice: Always put a weight on the bar that you’re 100% confident in making. Don’t risk wasting energy, losing kilos on your total, or putting yourself in harm’s way.

9. Bring any warm-up modality that you need

If there are certain pieces of equipment that you need for a powerlifting warm-up, then make sure to bring them with you on game day.

Background and Problem

Each warm-up environment is going to be slightly different. If the competition is held inside a gym, then you’ll probably have access to the equipment available. If the competition is held at a hotel or conference centre, then the chances of having any extra equipment for warming up is low. You should know your equipment needs and ensure you bring anything you need.

For example, when I compete it’s really important for my bench press warm-up that I have a dowel. I use the dowel to work my way through various shoulder rotations to increase blood flow and mobility. It’s not typical to find a dowel in every warm-up room, so I bring my own. Other warm-up tools you might need are foam rollers, lacrosse balls, or bands.

Advice: Don’t rely on the competition to have the equipment you need for warming up. Bring your own.

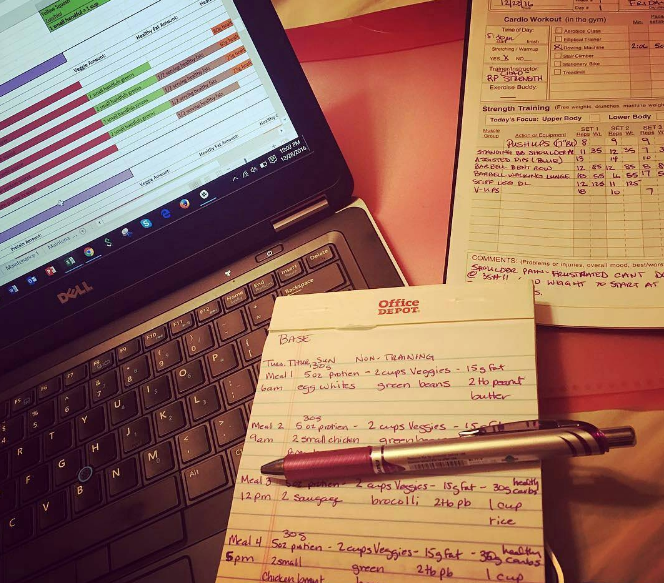

10. Think about your food choices ahead of time

At your first powerlifting meet, you want to make sure you are fueling your body properly with similar types of food that you already know you respond well to. Nutrition is not my area of expertise, so I asked Maggie Morgan from Married to My Macros for her advice on game day nutrition. Maggie is a world-level Canadian powerlifter and nutrition coach.

Here’s Maggie…

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bfbe3SXgv8E/

Background and Problem

Many lifters go into competition day thinking that they just need to ‘eat a lot’ and beyond that, the quality, timing or composition of their meals doesn’t really matter. This mentality can negatively affect your performance for a couple reasons:

- High calorie foods tend to also be high in sugars which provide a short burst of energy, followed by a crash and burn. If you’re doing a 3-lift competition, you have a long day ahead of you. We want to make sure that your energy remains as consistent as possible throughout the day so you aren’t completely tanked by the time deadlifts roll around.

- Often lifters see game day as an opportunity to indulge in whatever food items they might have been avoiding leading up to competition in an effort to prepare (this is how I approached my first few competitions, too). Donuts, candy, cookies, muffins – the list goes on and if you’ve ever been in the warm up room at a powerlifting meet, you’re likely familiar with what I’m referring to. Now, if you don’t regularly eat these food items, particularly in and around your training sessions, how are you to know how you will respond? Maybe you feel bloated, lethargic or you get a stomach ache. These are certainly situations we want to avoid in the middle of a competition.

Game day nutrition will certainly look different for each individual athlete, but there are a few hard and fast rules that will pertain to almost everyone.

Even when following these recommendations, always do what feels right for your body. Never make yourself uncomfortable by eating too much or eating something you are unfamiliar with. As with everything else you’re learning about yourself and your body at your first competition, you will be learning what nutrition protocols work best for you.

1. Eat a lot of good carbohydrates.

About two hours before you begin lifting as well as in between lifts, you want to have a meal that is really high in carbohydrates, but the right kinds of carbohydrates. The carbohydrates you choose should be low in fibre and low on the glycemic index as this will provide a steady stream of glucose available to your muscles.

Examples of the best pre-competition carbs include:

- Sweet potatoes/yams;

- Baked potatoes

- Quinoa and legumes

- Rice, pasta, oats, buckwheat and cereals

When you’re warming-up for your lifts, you’ll want to be providing your muscles with some quick release carbohydrates, such as fruit, coconut water, baby food or gel packs.

2. Never introduce new foods or something you don’t usually eat day of competition.

Even if it’s really high on the ‘recommended foods’ list above – stick to what your body knows. There is no magic formula, just as there is no magic food that will make you perform better on competition day.

3. Stay really well hydrated.

Hydration is key – even a 2% drop can decrease your performance by up to 25%. Drink early and often. You’d really have to try hard to overdo this. Don’t be afraid of an electrolyte replacement either, preferably one low in sugar (this is why coconut water is great).

In Summary: Nutrition is often something that is overlooked when preparing for a powerlifting competition, yet can have such a significant impact on your performance, both in training and in competition. If you plan to compete in powerlifting, you are already investing so much time into your training that you should want to get the biggest return on your investment. Dialling in your nutrition and fueling your body to perform will allow you to do so.

11. Ask A Lot of Questions to Those Around You

One of the primary goals for your first meet should be to learn as much as possible about the competition itself. One of the best ways to learn is to ask questions to those who are more experienced.

Background

It’s impossible to know absolutely everything about competing in powerlifting until you’ve done several meets. I tell my athletes that it usually takes around five competitions to fully understand how a competition runs: how the rules of the sport apply in different situations, how warm-ups are structured, how the schedule and flights are organized, how attempts are managed by the score-table, how placings are determined, and so on and so forth.

Most of these things you will simply ‘learn by doing’.

But when you come across a situation where you don’t fully understand, you should not feel intimidated to ask questions to other athletes or referees.

Some of the questions you might find yourself asking are:

- How do I get my rack heights and where do I get them?

- How much time do I have before stepping onto the platform for my first squat?

- Can I change my opening attempt? And if so, what’s the protocol in doing so?

- How much time do I have in between attempts?

- Can I use ammonia or smelling salts?

- Can I re-rack the bar after taking it off the rack?

You can see that you likely wouldn’t be asking these questions before a competition. But, when you’re in the midst of competing, you find yourself having all sorts of questions based on the events of the day.

My advice: Learn as much as you can throughout the competition by asking other athletes or the referees your questions. They will be more than happy to help you.

12. View the First Meet As the ‘First of Many’

Go into your first powerlifting competition with a long-term perspective. The first meet should be a stepping stone to many other competitions that follow.

Background and Problem

Athletes often approach their first meet like it’s their last:

- They put a lot of pressure on themselves by having high expectations for what they should be able to lift.

- They are hesitant to compete unless they know they’re going to win.

This is the wrong perspective…

Before worrying about the numbers you lift or winning, you need to do several competitions to learn how to compete effectively. Here’s the right mindset to adopt when competing for the first time:

- The first meet will set your baselines for future training and progression. Until you’ve competed, all of your numbers are simply based on training. Training numbers are not as important as what you can do in a meet context. The numbers after your first meet establish your capabilities. They provide an objective measure of your 1 rep max strength, which will determine how you proceed in training and how you evaluate your performance from one test event to the next. Competing in several competitions allow you to benchmark yourself, adapt training based on those benchmarks, and continue progressing.

- The first meet is about learning the ‘unknown variables’. On game day, you’ll be faced with all sorts of meet day variables that will likely impact your performance – most of which will fall outside of your own control. These variables are not known until you compete for the first time. Once you’ve competed in several competitions, you’ll be able to understand all of the meet day variables that impact performance. You’ll feel more comfortable in the competition environment, and this will help you realize your potential on the platform.

- Focus on transferring your current levels of strength onto the competition platform. Many first time powerlifters might set lofty goals for themselves that far exceed the numbers they’ve done in training. The reality is that it will be very hard to replicate your training numbers at your first competition given all the meet day factors at play. Typically, you will need to compete in several meets before improving your ability to transfer your strength from training to competition. For the first meet, view success as the ability to replicate your training numbers. This would be an accomplishment because you’re expected to do these lifts under the pressure of a competition environment.

My advice: Within the first year of powerlifting, compete often and hone your skill of competing before being overly concerned with the numbers you lift or about winning.

13. Learn From Your Missed Lifts

It’s realistic to expect that at some point you will miss a lift in competition. When this happens, you’ll want to clearly understand why you failed the lift, and if there’s anything you can do to prevent this from happening on the next attempt or in the future.

Background and Problem

You can miss a lift for all sorts of reasons ranging from not being strong enough to not following a specific movement standard. If you’ve missed a lift because you’re not strong enough, then this is typically something that will require a more long-term programming approach to correct. In the moment, it will be very hard to correct a ‘strength issue’.

You’re either strong enough or not…

However, if you’ve missed a lift because you didn’t follow a specific movement standard, then this is something you can most certainly correct for the next attempt. For example, let’s say you just finished your second attempt bench press. It felt fairly easy and it wasn’t hard from a strength perspective. But, it was red-lighted and the lift doesn’t pass. In this case, it would appear that one of the movement standards were not followed.

/ Shutterstock

When this happens, the referees will not automatically say why you missed the lift. The athlete will walk off the competition platform and wonder why the lift didn’t pass and be clueless on how to correct their technique for the next attempt. I’ll often hear athletes come off the platform and say, “I think the lift didn’t pass because my butt came off the bench”. Then, someone else turns to them and says, “actually I think it’s because your foot moved”.

Well, which is it? At this point, it’s entirely speculation. Don’t let this be you. You should always know why a lift doesn’t pass.

The problem is that the referees will only tell you why you missed a lift if you ask them. If you don’t ask them, they are generally instructed not to approach athletes because it would:

- Show a bias toward one particular athlete over another

- Slow down the timing of the event if they had to explain every attempt to every athlete

However, it’s your right as an athlete to ask the referee why the lift didn’t pass. Once you ask, the referee has an obligation to explain it to you. So if you miss a lift, always ask why it didn’t pass. You’ll then be 100% certain on what you need to do for the next attempt. This is also good information to gather because it will allow you to go back to training being more diligent with your movement standards. If you miss a lift based on a technical infraction, then making it a priority in your workouts will allow you to become a better powerlifter.

My advice: Never walk off the platform wondering why a lift didn’t pass. Always ask the referee.

14. Start a Post-Competition Journal

After you compete, you should spend time reflecting on what worked, what didn’t, and what you could do differently next time. These reflections should be written down within a day of competing when everything is still fresh in your mind.

Background

Until you compete, you’re relying on what other people say will work for you on game day. You’ll have read this article, talked with other powerlifters, and got some advice from your coach.

However, all those suggestions are through the lens of other people’s experiences – not yours. This is not to say that other people’s advice shouldn’t be valued. Of course, you will learn a lot from others. But, once you compete, you now have your own set of experiences to understand how you can improve performance.

What I encourage my athletes to do after each competition is to write down:

- Things that worked

- Things that didn’t work

- Things to do at the next competition

- Things to do in training

It’s important that these questions are responded to in writing so that you maintain a record overtime of how to improve performance. Furthermore, the sooner you can sit down and reflect about your meet day, the more accurate and detailed your responses will become.

Here are some examples from my own athletes’ post-competition journal reflections:

Things That Worked

“This meet I realized that I like to be more social backstage. I like to have friends with me and talk to other athletes. It helps me stay calm and not get stressed out. In the past, when I don’t have friends backstage, or I’m isolated, I overthink my lifts. When I’m not taking my lifts so seriously, I do better.”

Things That Didn’t Work

“I need to have a longer time between my last warm-up and opener. I didn’t feel like I had the best warm-up timing — especially on squat. I don’t like to feel rushed, and I need time to go to the washroom before my opener. Ideally, I would like 15-minutes between my last warm-up and opener.”

Things to Do At the Next Competition

“The warm-up room was super cold! For the next competition, I need to bring warmer clothes. Even if I wear them or not, it’s always better to be prepared. Also, I didn’t anticipate the long breaks in between squat and bench, and bench and deadlift. I need to learn how to relax more during long breaks. At the next meet, I’m going to find a quiet area and listen to music, and not worry about warming up until instructed.”

Things to Do In Training

“I need to work on my depth for squats and overall just get stronger in the hole. I’d like to do more heavy pause squats and work on bracing my core so that I don’t lose tightness when the weight gets heavier”.

The exact reflections will vary from person to person, but this gives you a framework for the types of things you should be thinking about following a competition. As you can see, there are several factors that go into performing at your best. For any variable you can control where you think it will make a meaningful impact on your performance you should document it and consider its impact on your training and the next competition.

My advice: Maintain a post-competition journal to understand your experiences as a powerlifter and how you can improve.

/ Shutterstock

15. Get Involved In ‘Non-Athlete’ Roles

To become involved in non-athlete roles, you should consider volunteering as either a spotter or loader or a scorekeeper.

Background

There are two reasons why you should consider volunteering for these roles:

- You will learn more about how a competition is structured. As a volunteer in these roles, you will see hundreds of attempts throughout the day. You will learn from athletes’ successes and failures, and how the various rules apply to different contexts. Throughout a day of volunteering, you’ll feel more confident knowing what you should or shouldn’t do on meet day to optimize your performance. Notwithstanding, you’ll learn the technique that goes into successful lifts or not.

- You will get connected to the powerlifting community more broadly. A powerlifting competition is run by volunteers. Without volunteers, powerlifting competitions wouldn’t exist. By volunteering, you will meet other athletes who choose to volunteer. These relationships allow you to connect with people in the sport you otherwise wouldn’t have the opportunity to do so. These could be people who you’re able to ask questions to, train with, or simply have a familiar face the next time you compete.

My advice: Consider volunteering for a competition before you compete, or volunteer at your first competition (in addition to competing).

Final Thoughts

When you make the decision to compete in powerlifting, there are several factors that go into performing at your best. You can be strong in the gym, but transferring that strength into the competition environment becomes challenging. The first competition should be a process of honing your skill of competing rather than setting lofty number goals for your lifts.

When possible, have a game day coach to assist you, understand the rules and equipment allowed, and be realistic with your attempt selection. Ask a lot of questions to those around you and take a long-term perspective with your career as a powerlifter. Once the first meet is under your belt, you’ll be more confident for each successive competition. Measure yourself not by the result of your first meet (like me bombing), but by your improvement over time and ability to learn from one competition to the next.

Feature image by Igor Simanovskiy / Shutterstock