Members of the military go through rigorous physical training and are required to make tremendous personal sacrifices. The difference in one’s day-to-day life between working in the military versus post service can be stark, particularly when it comes to physical fitness and finding a renewed sense of community.

That is why we are going to delve into strength sports as the viable option for veterans. Not only can strength sports help veterans maintain or regain their physical fitness, but they can also help fill the need for a friendly support structure made from a community of likeminded individuals.

In addition to better educating about how strength sports can build body strength and community, this article aims to provide resources within the strength sports world and info on its various competitive events.

The Appeal of Strength Sports For Veterans

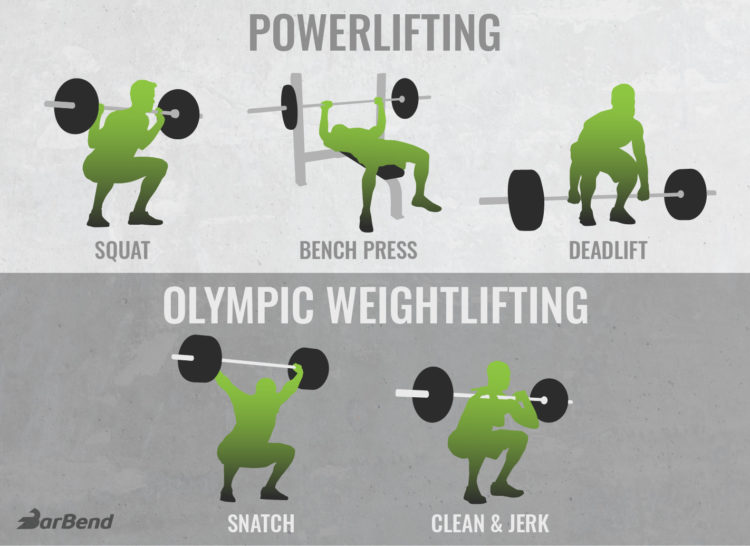

Strength sports — powerlifting, Olympic weightlifting, strongman, and CrossFit — can be just as much about improving yourself as it can be about fueling a sense of competition against other athletes. The goals strength sports athletes set for themselves can be flexible.

So strength sports can be beneficial for anyone by providing structure and routine as well as improving physical and mental health. Let’s talk about what they can offer specifically for veterans.

Physical Fitness

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) noted in a 2017 study that the majority of the veterans living in the U.S. have significant weight issues: (1)

Among the nearly 21 million military veterans living in the United States, 64.0% of women and 76.1% of men are overweight or obese, higher rates than in the civilian population (56.9% of women and 69.9% of men).

— Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

For Army retirees, the average amount of weight put on in their first year out of the military is four pounds. More significantly, it leads to a trend of continuous weight gain.

A study by the U.S. Army Public Health Command found that “obesity rates for [veterans] are significantly higher than the general population of the same age. In addition, the rate of obesity among these Army retirees is twice as high when compared to active-duty soldiers.”

Lt. Col. Sandra Keelin, a registered dietitian at the U.S. Army Public Health Command, believes that the likely cause of the weight gain for retirees is caused by a combination of decreased physical activity without an adjustment to lower overall caloric intake.

Strength sports can help establish a routine for physical activity, which can enable the consistency needed to build strength. A study in the Journal of Sport Rehabilitation found that training each muscle group twice per week provided the most benefit. (2)

For veterans looking to improve their overall health, the Army suggests using the U.S. Army’s Performance Triad, which focuses on sleep, activity, and nutrition. In terms of activity, strength sports can be the avenue to increase physical activity while offering additional motivating factors beyond just wanting to “be more active”.

Let’s discuss some of those factors.

Community

According to a Pew Research Center survey conducted on June 3rd, 2019, 47% of veterans say adjusting to civilian life after leaving military service was difficult. (3)

This held true regardless of the kind of environment veterans came home to — be it rural, suburban, or urban. A 2017 study conducted by the Center for Innovation and Research at USC School of Social Work determined that “overall trends show that moving into civilian life continues to be difficult regardless of location.“(4)

Involved in that study was Michael Henderson, a former Marine who served for four years in Iraq, who found that college provided a structure that helped him create a life separate from the military.

“You get used to everything being in lockstep and then all of a sudden you have to create that routine for yourself. I think that’s where a lot of friends that I’ve had from the Corps have fallen. They didn’t have something to rally behind.”

Strength sports training and its community may also be able to serve that function: providing structure for veterans who need it.

Although CrossFit is a step more in the functional fitness space — training that prepares the body for everyday movements and activities — it does incorporate Olympic weightlifting. Here is what CrossFit Westchester President Chris Guerrero said when it comes to building a fitness community:

“The community is a place where the vulnerable feel comfortable to fail as often as they succeed. It’s through failure that true growth occurs…where pushing yourself is encouraged, as that is where progress is made. At the end of the day the community is a place where friends of all ages and walks of life come together. We are literally trying to melt their stress away.”

Stress Reduction

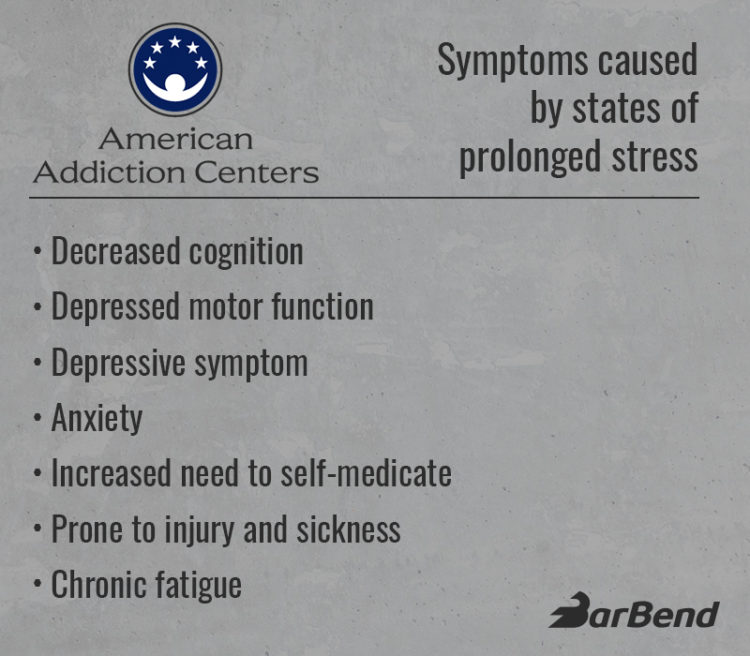

Serviceman and servicewomen of the U.S. Military often endure extended periods of unrecognized stress while on active-duty that have lasting effects even after retiring. According to the American Addiction Centers (AAC):

“Although stressors individually may not cause the toxic effects, together they can create a cascading additive effect.” (5)

Here the AAC’s list of symptoms caused by states of prolonged stress:

[Read More: The Best Mobility Exercises, PT-Approved]

Stress can also be a deterrent to physical activity. According to a review in the Journal of Sports Medicine, the experience of stress impairs efforts to be physically active. (6)

So how can strength sports and their communities help relieve these symptoms?

Physical fitness by itself has been proven time and time again to help relieve stress. As little as eight weeks of resistance training can reduce cortisol — a hormone that affects the autonomic nervous system — and stress among people with PTSD, according to study from the Neuro Endocrinology Letters. (7)

Furthermore, training has a significant positive effect on sleep. A study in 2018 published in Sleep Medicine Reviews concluded that “chronic resistance exercise improves all aspects of sleep, with the greatest benefit for sleep quality.” (8)

Incorporating a lifestyle of consistent training in order to reduce stress is undoubtedly supported by the science as well as many veterans personal points of view. The Wounded Warrior Project (WWP) conducted a survey that revealed that nearly 30% of respondents said physical activity proved helpful for their mental health.

A study published in The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association revealed that physical activity is even more effective when training with others. Researchers found that physical training in groups lowered stress levels of participants by 26 percent more than individuals who trained alone.

Endeavoring to become a part of the strength sports community, whether in person or online, can also provide the necessary accountability to not only show up and train, but also to train harder than individuals otherwise would by themselves.

[Read More: The Best Back Exercises and 5 Back Workouts for More Muscle ]

Competition

Competition is a useful motivational tool to get to the gym and a means to hold oneself accountable. In addition, competing against athletes who are perceived to be stronger by a given metric can also help you perform better.

A study from the Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology determined individuals who exercise with a more capable partner improved their athletic performance by 24 percent (9).

Training for competition can also reduce stress. A study the found that frequency, duration, and intensity of organizational stressors — a series of twenty-three items related to stress — lowered for six weeks following a competition that an athlete prepped at least six weeks for. (10, 11)

Prepping for competition has also shown to reliably rebuild confidence of wounded service personnel. So much so that a review in Prosthetics and Orthotics International concluded:

“sport…should be more widely recognized as a component of rehabilitation. This is not just for the role that sport can play as a tool for rehabilitation but also for the intrinsic and extrinsic benefits that participation in elite sport can offer.” (12)

Special Considerations For Veterans Who May Be Disabled

For veterans who have suffered a physical injury that would prevent them from competing in non-adaptive competition, there are measures put in place so that they are still able to compete.

Powerlifting

Athletes with disabilities compete in the bench press on an adapted competition bench against other competitors in their weight class. Competitors lower the bar to the chest and then press it upwards to arms’ length until elbows are locked out. As with most powerlifting meets, athletes are allowed three attempts.

Powerlifting — more specifically the bench press discipline — has been performed at the Paralympic Games since its inception in 1964.

Olympic Weightlifting

Both the Olympic lifts — snatch and clean & jerk — are involved in adaptive Olympic weightlifting. Adjustments can be made to suit specific needs a particular athlete might have but the basic movements and goals of each lift remain the same — locking the barbell out overhead.

Both Olympic lifts can be single arm lifts performed by athletes who only have access to one arm. Modifications to the snatch can be done for athletes who require a wheelchair. An example of how a snatch from the seated position looks can be seen below via Sarah Rudder’s YouTube Channel:

Strongman

There are sanctioned adaptive strongman events held at higher competition. One of the most well known is the adaptive strongman category at the Arnold Classic.

Strongman events can vary depending on the competition and the equipment used, but some disciplines such as the deadlift are usually represented in some form. For adaptive strongman athletes, adjustments can be made to ensure that the mechanics of the discipline remain. An example of this is the seated deadlift.

The video below from Guinness World Record’s YouTube Channel illustrates the movement — adapted strongman and British Army veteran Martin Tye pulling a world record 505kg/1,113lb seated deadlift:

The deadlift takes place at 3:08

Other adaptive strongman events include the Hercules Hold, the vehicle/sled pull, a variation of the Atlas Stones, Cyr dumbbell, bag toss, and the sandbag carry.

CrossFit

Adaptive CrossFit practices the same fundamental movements of CrossFit, but the equipment may be modified to fit a specific athletes’ needs. Adaptive versions for a most workouts of the day (WOD) are also available.

CrossFit supports multiple divisions for adaptive athletes at higher level competitions including the CrossFit Games — adaptive seated and adaptive standing. Check out this clip below from CrossFit Games’ YouTube channel of the 2018 CrossFit Games highlighting both divisions:

Movements included: snatches, burpees, ball slams.

Organizations Dedicated To Strength Sports For Veterans

There are many organizations that offer a range of help to veterans. That help can be in the form of grants for gym memberships and personal training, customized programs to help reach set goals, a support system able to offer guidance when needed, and much more.

Catch A Lift

Founded in 2010, Catch A Lift (CAL) Grant Program is a non-profit organization that helps “post 9/11 combat wounded veterans regain their mental and physical health through gym memberships, in home gym equipment, personalized fitness and nutrition programs and a peer support network.”

Eligible applicants are veterans who served in the post 9/11 OEF/OIF wars in Iraq or Afghanistan (other areas such as Kuwait are considered on a case by case basis), were injured in combat (PTSD is a combat injury) and are rated by the VA at 50% or above for combat injuries. At least one combat injury has to be rated at 30% or higher with the cumulative rating for combat injuries being 50% or greater. Any Veteran with a Purple Heart from Iraq or Afghanistan will fit preliminary requirements and be able to go on to the interview process.

While CAL does have civilian coaches, the bulk of our coaching staff is made up of veterans who are also CAL members. They have likely been where each veteran has been at some point in their fitness journey. This allows them to better understand the challenges that new members face.

CAL has raised over $6.2 million in their efforts to offer yearly grants aimed at financing programs to a veterans’ specific fitness needs. They also offer further education in the fitness space and events throughout the year to build camaraderie among those in the program. They currently have over six thousand veterans in the program.

Connect with CAL via their website.

Adaptive Training Foundation

Adaptive Training Foundation (ATF) is a non-profit organization that works with veterans and others who have suffer life-altering injuries to “bridge the gap from basic functional rehabilitation to adapted sport.”

Their program is threefold:

- First, adaptive athletes train for nine weeks of personally customized training with the support system of other athletes who have endured similar hardships.

- Second, athletes train three times a week to achieve a goal previously determined during phase one while simultaneously helping build the community to better ensure accountability.

- Third, elite adaptive athletes can participate in customized performance training to eventually compete in high-level competition such as the Paralympic Games and the Invictus Games.

Connect with ATF via their website.

Wounded Warrior Project

The WWP is a non-profit organization founded in 2003 that provides a variety of veteran programs and services that promote mental and physical wellness as well as career counseling and other more specific needs. WWP has previously worked with powerlifting federations such as the Xtreme Powerlifting Coalition (XPC) to hold powerlifting clinics for veterans.

Connect with WWP via their website.

Gerofit

Gerofit is a personalized strength training program through the VA to help improve mental and physical health for older veterans. It is currently available at VA healthcare systems nationwide.

You can find the closest Gerofit location near you via their website.

U.S. Paralympics & Paralympic Games

The United States Olympic Committee partners with the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) on the VA Paralympic Program. They provide a monthly allowance to support Paralympic-eligible veterans in their efforts to represent Team USA at the Paralympic Games and other international competitions — allowances range from $566.97 up to $1,070.40 depending on the number of dependents.

Learn more about the U.S. Paralympics via their website.

Invictus Games

The Invictus Games is multi-national sporting event for wounded servicemen and servicewomen that began in 2014 and has been held in London, Orlando, Toronto, and Sydney. The 2020 and 2022 Games will take place in The Hague, Netherlands and Dusseldorf, Germany, respectively.

Learn more about the Invictus Games via their website.

Department of Defense Warrior Games

Established in 2010, The Department of Defense (DoD) Warrior Games puts adaptive athletes representing each branch of the U.S. Military as well as other countries militaries from around the world in head-to-head competition across thirteen sports including powerlifting.

Learn more about the DoD Warrior Games via their website.

Insight From Veterans In The Strength Sports World

There are many veterans already weaved into the fabric of the strength sports community as athletes, coaches, mentors, and advocates. We had the opportunity to acquire the insights of several of them so that they could offer their knowledge and experience of how strength sports changed their life for the better once retired from military service.

KC Mitchell

Mitchell made history on January 7th, 2017 at the United States Powerlifting Association (USPA) American Cup Los Angeles Fit Expo where he became the first ever amputee (left leg) to compete in a full USPA sanctioned powerlifting meet in the non-adaptive open division at the age of 31. He competed in the -110kg weight class and finished in second place with a 662.5kg/1,460.5lb total.

You can see Mitchell’s performance at that event below courtesy of Apeman Strong’s YouTube channel:

Mitchell was severely wounded overseas by an explosive device that his unit drove over. He made the decision to amputate his leg rather than go through the long, painful, and likely indefinite process of physical therapy.

Strength Project released a short video in 2016 documenting some of Mitchell’s training and his thoughts on getting in the gym after losing his leg. During his training for that full power USPA competition, Mitchell was able to hit full depth in his squat of 147kg/325lb — something he was unsure would even be possible:

“I would rather be crushed under hundreds of pounds than to one day not know what I was capable of. I didn’t give up, people were there to push me, and it was emotional for me when I did it. It wasn’t a lot of weight. It was the point that I did it.”

He would go on to successfully squat 197.5kg/435lb in competition.

When asked what he would he would say to someone going through something similar to what he went through, Mitchell said:

“The only way to get past what you’ve been through is to grab the bulls by the horn and start putting in that work. Nothing is going to get handed to you. If you just get in [the gym] and just grind it out every day, things will progress, and things will get better.“

Jason Livingston

Staff Sergeant (U.S. Army ret.) Jason Livingston is a member coach at CAL who got into powerlifting after retiring from the Army as a helpful way to handle PTSD.

“My wife sat me down and told me that I needed to find a way to deal with my PTSD, stress, and anxiety. I was becoming very shut off from everything around me. I needed a healthy outlet, so she brought me information for Catch A Lift. I am extremely grateful my wife pushed me in the fitness direction.”

Livingston joined the CAL program at a bodyweight of 270lb. He is currently 190lb — an 80lb weight loss. Although dropping the excess pounds has been a huge positive, Livingston finds the largest benefit to be the easier time he has coping with his PTSD. He does not rely on medications or turn to alcohol when feeling anxious, and finds comfort in the support system of others provided by CAL.

“…instead of reaching for a beer, I’ll lift. I’ve seen too many veterans go the opposite way with that and commit suicide or end up in trouble. Being a part of the fitness community — specifically with Catch A Lift fund — is like being back in a line unit. You have all of these people that care about you and understand what you are going through. Whether it’s just getting healthy or getting your mind right, they are there.”

[Read More: One-Month Push-Up Workout Plan for More Push-Ups]

Obstacles

For Livingston, the military is a demanding environment to be in both physically and mentally. However, it enabled his drive to work harder to be stronger and faster than the guys around him. And being Non Commissioned Officer, he was responsible for enforcing the standards.

But when he first started lifting after leaving the military, he had a lot of hurdles to overcome. He was dealing with spinal and knee injuries on top of his heavier bodyweight. He struggled to believe in himself.

I had given up on myself. I was fat, out of shape, in pain, and dealing with PTSD, so excuses came easy.

— Staff Sergeant (U.S. Army ret.) Jason Livingston

This was all coupled with a poor diet of emotional eating. To him, he was already past the point of no return so “what’s one more cheeseburger or pizza going to hurt?”

“I had to have an honest conversation with myself and make the commitment to change.”

— Staff Sergeant (U.S. Army ret.) Jason Livingston

That change was powerlifting:

“You’re always working towards that next goal or PR, which for me is hitting a 500lb deadlift. And once you hit that PR, you’re never satisfied. You want to seek self-improvement and hit that next goal. In the Army, we constantly pushed how far our bodies would go. That is what I think appeals to so many veterans, the drive to push yourself to become better than you were yesterday.”

Wrapping Up

The science and many already ingratiated in the community agree that strength sports can be a meaningful avenue for veterans to improve their fitness, reduce stress, and become part of a reliable support structure.

For veterans, whether new to strength sports or a more seasoned athlete, there are several well established organizations that can help them get a foothold in the community and build a program designed for their needs.

References

- Elizabeth Tarlov, Shannon N. Zenk, et al. (2017). Neighborhood Resources to Support Healthy Diets and Physical Activity Among US Military Veterans. Original research; volume 14. CDC.

- Theodore Kent Kessinger, et al. (2019). The Effectiveness of Frequency-Based Resistance Training Protocols on Muscular Performance and Hypertrophy in Trained Males: A Critically Appraised Topic. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 1-8.

- Ruth Igielnik. (2019). Key findings about America’s military veterans. Pew Research Center.

- USC Staff, et al. (2017). Service Members Speak Out on Difficulties of Transitioning to Civilian Life. The University of Southern California Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work.

- James White, LT USN (SEAL) RET. PA-C, MBA-C, Laura Close. (2019). The Forgotten Ones: A Military Veteran’s Report on Stress’s Effects. American Addiction Centers.

- Matthew A. Stults-Kolehmainen, Rajita Sinha.(2014). The Effects of Stress on Physical Activity and Exercise. Journal of Sports Medicine, 44(1): 81–121.

- Michal Wilk, et al. (2018). Endocrine Response to High Intensity Barbell Squats Performed With Constant Movement Tempo and Variable Training Volume. Neuro Endocrinology Letters, 342-348.

- Ana Kovacevic, et al. (2018). The Effect of Resistance Exercise on Sleep: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 39:52-68.

- Deborah Feltz, Norbert L. Kerr, Brandon Irwin. (2011). Buddy Up: The Kohler Effect Applied to Health Games. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 33(4):506-26

- Gareth A. Roberts, et al. (2019). A Longitudinal Examination of Military Veterans’ Invictus Games Stress Experiences. Frontiers in Psychology Journal, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01934

- Rachel Arnold, et al. (2013). Development and Validation of the Organizational Stressor Indicator for Sport Performers (OSI-SP). Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 35(2):180-96.

- Nachiappan Chockalingam, et al. (2012). Should Preparation for Elite Sporting Participation Be Included in the Rehabilitation Process of War-Injured Veterans? Prosthetics and Orthotics International, 36(3):270-7.

Feature image via Shutterstock/Oleksandr Zamuruiev