There are elite circles of the strength world where even the ability to squat triple your bodyweight won’t get you through the door.

We’re talking about the peaks of extreme bodyweight strength, where bodyweight masters have the kind of coordination, relative strength, and kinesthetic awareness that blows many athletes out of the water.

Today, we’re showing you how to join their ranks with an extraordinarily cool exercise that has significant carryover to heavy lifting: the one-armed chin-up.

“One of the primary benefits of the one-armed chin-up is you’re building a lot of pulling, lat and grip strength,” says Greg O’Gallagher, a trainer, one-armed chin-up afficionacdo, and founder of Kinobody. “So it has a lot of carryover to the deadlift and other pulling exercises.”

He adds that the movement is also fantastic for bicep strength and even core stability.

“To nail the movement, you need to use your core and upper body in conjunction as you’re pulling. I’d say most people who try the one-armed chin-up aren’t able to use as much strength because they aren’t able to integrate their core with their pulling.”

So, this exercise will skyrocket your grip, bicep and lat strength, improve core stability, and because it’s a closed chain exercise, it may recruit more muscles and require more coordination, balance, and neurological stimulation than a simple lat pull-down.

Here’s your progression.

How to Dominate the One-Armed Chin-Up

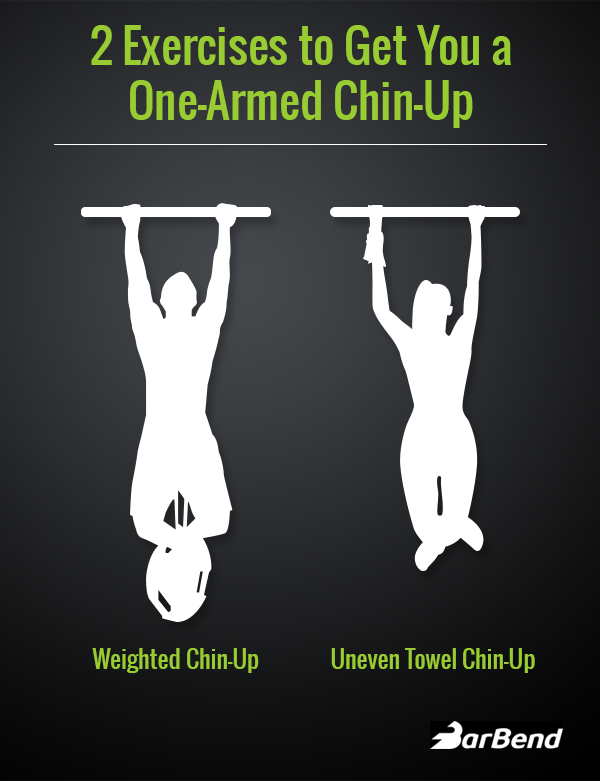

O’Gallagher has a pretty simple, two-exercise program for getting to where you want to be.

“Everyone overtrains it,” he says. “They’ll do weighted chin-ups on Monday, explosive pull-ups on Tuesday, high rep chin-ups on Wednesday. Really, you only want to train this movement every five days or so, or about eight times in a six week period.”

He likes to focus on one exercise for six weeks at a time. The first: weighted chin-ups, reverse pyramid-style.

Each time you train for the movement, perform three sets at four, five, and six to eight reps a piece, dropping your overall weight (that’s you plus the attached weight) by ten percent or so per set. A goal to shoot for before attempting a one-armed chin-up is four or five reps with a weight that’s about sixty percent of your bodyweight.

It’s a pretty audacious goal, but this is a pretty audacious exercise, and the amount of strength it takes to perform a one-armed chin is probably as much as it takes to do a regular chin-up with eighty percent of your bodyweight attached. And yes, that’s probably going to take a lot of time. But if this is your goal, it needs to be met with focus and patience.

After six weeks of training with weighted chin-ups, switch to the second exercise: towel assisted chin-ups. This is like a regular chin-up, but one hand is holding onto a towel that’s wrapped around the bar. (Like in the video above, except that the gentleman is performing an assisted pull-up, not a chin-up.) The idea is to hold the towel as low as possible and to try to use that arm less and less as you become progressively stronger.

“With these, you wanna go pretty low on reps, two or three max,” says O’Gallagher, recommending a maximum of four total sets. “Any more than that, and you’ll start losing too much strength in your main arm and compensate by using both arms.”

If these are too difficult, try side-to-side chin-ups first, wherein you bring the chin to one hand at a time, instead of between them. This’ll help to build up the requisite unilateral strength.

Alternate back and forth between the exercises every six weeks. If you aren’t getting anywhere, try incorporating negative one-arm chin-ups, reducing or eliminating other pulling exercises and, though we rarely say this, losing some weight. O’Gallagher says that if he or she is lucky, a recreational lifter could hit their goal in six months.

Areas of Concern

It can be hard to think of a bodyweight exercise as particularly stressful or injurious, but at the elite level, they certainly can be. The one-armed chin-up puts an enormous amount of stress on the grip, bicep, shoulder, and lat; elbow injuries and bicep tears are particularly common.

“One way to remedy common problems is to vary the grip diameter by wrapping the bar,” says Steve Horney, DPT, CSCSC a physical therapist based in New York City. “That modifies the place of stress on the common origin of the flexor group.”

To warm up and lower the risk of injury, Horney recommends soft tissue work, like rolling a lacrosse ball, on the forearm, biceps and lats. Training the wrist flexors and extensors both eccentrically and concentrically is also a good way to prepare the area. He likes using a rubber bar to train the wrist extensors, as shown in the video below.

“Another area of concern is shoulder impingement,” he adds, “because if athletes get tired during the movement and rest in the bottom of the chin-up, they are more prone to pathological pinching of the rotator cuff, bursae, and long head of the biceps.”

Translation: keep the reps very low and don’t hang around. (Get it?)

Final Words

This is a really hard, really cool exercise that has a whole lot of payoff for strength athletes. But don’t get too obsessed with attaining this extraordinarily rare ability.

“It’s something that’s fun to shoot for, but even if you don’t get there, you’ll get tons of benefits if you’re just training for it,” says O’Gallagher. Think of it like aiming for a 600-pound deadlift. Even if you never get your number that high, the progress you make while chasing it can bring almost as many benefits.

So. Got some time on your hands?

Featured: @daliborpetrinic