In the last few weeks, the bench press has gotten a ton of attention across the internet and social media. Strength athletes from all walks of life are searching and talking about the bench press more than normal, and some of this could be credited to CrossFit® integrating the press into their 2018 CrossFit Games Regionals competition.

At the root of the bench press the concept of its form is simple: Lie down on a bench, grab a barbell, bring it down to the chest, and press it back up. There’s a simplistic beauty that comes along with movements like the bench, but is it really that simple?

https://www.instagram.com/p/BifRy1Gl0pb/

Yes and no. The bench press is a static compound movement that moves a barbell through the transverse plane of motion. It’s relatively simple when compared to something like a clean & jerk, but like with most things in strength sports, the devil can be in the details. This article will look at the elbow “tuck” and “flare” concept in the bench press and how to find what will work best for you.

Understanding Bench Press Elbow Flare and Tuck

Elbow tuck and flare can be defined as the degree in which the elbows move in relation to the torso throughout the bench press. When people say “tuck” they’re describing the amount the elbows get pulled in to the sides of the torso when bringing the bar to and away from the chest. The description of “flare” is the degree in which the elbows come out from the body, aka move more parallel to how the arms would look if they were extended directly outwards.

[Years ago, Broses passed along these 10 Commandments of the Bench Press.]

Check out the video below where Greg Nuckols summarizes his rationale for proper elbow positioning in the bench press. He states that he likes the cue “tuck and flare” to create an equal distribution between the prime movers in the bench.

Both of the terms “flare” and “tuck” get thrown around a lot when learning and fixing bench press form, and that’s where it can get tricky for newer athletes. At the end of the day, too much of either can be a bad thing when it comes to executing proper form and moving weight in an efficient manner.

This being said, it’s also important to avoid over-analyzing this concept and moving to a state of paralysis by analysis. At times, arguing the amount of tuck to a finite degree can limit an athlete’s ability to find their proper pressing form catered to their body’s needs, but more on that below.

In general, the proper bench press will land a barbell on the chest at a point where the elbows are roughly under the bar and where the hands are stacked atop the elbow. In general, this position will provide an athlete with a natural amount of tuck/flare catered to their body’s natural/comfortable position. Understanding this concept will help increase the amount of force you can transfer into the bar. For more bench press help, check this guide.

Finding Your Ideal Bench Press Elbow Position

So, how much flare and tuck is too much for proper bench press form? To help provide context and tips on the topic, I reached out to Jordan Feigenbaum, MD, and founder of Barbell Medicine. Feigenbaum is an experienced 198 lb (90kg) powerlifter and has been strength coaching a variety of athletes for over ten years.

What’s one way/tip you like to use to help athletes find the amount they should tuck the elbows in the bench? Is there a general rule of thumb someone can use?

Feigenbaum: The amount of tuck is going to be based on the grip width and touch point mainly, which are somewhat dependent variables. The narrower the grip, the lower the touch point on the chest, which requires more elbow adduction (tuck). A wider grip produces a higher touch point comparatively and less tuck.

[Need more bench press variations? Check out these three from Ben Pollack!]

When determining the grip width it’s really more of what works best for a lifter in the context of using a style that allows them to bench press consistently and frequently over a long period of time. Some people can’t tolerate a lot of benching with a narrow or wide grip, and trying to force a square peg in a round hole is a bad idea.

Ultimately, the amount of adduction is dependent on the grip width and touch point. With that in mind, the ideal amount of adduction produces a vertical forearm when viewing the lifter from the front and profile views. This represents the most efficient way to transfer force from the shoulder girdle, through the arms, and to the barbell.

So, in terms of tucking, is there a one-size-fits-all degree of adduction? If not, how can athletes find optimal tuck based on their arm lengths and lifting style?

Feigenbaum: For the amount of tucking, again it’s going to depend on grip width and touch point. Within that construct, the anthropometry of the lifter, e.g. shoulder width, humerus length, torso width, and so forth, are all going to determine the amount of adduction/tuck.

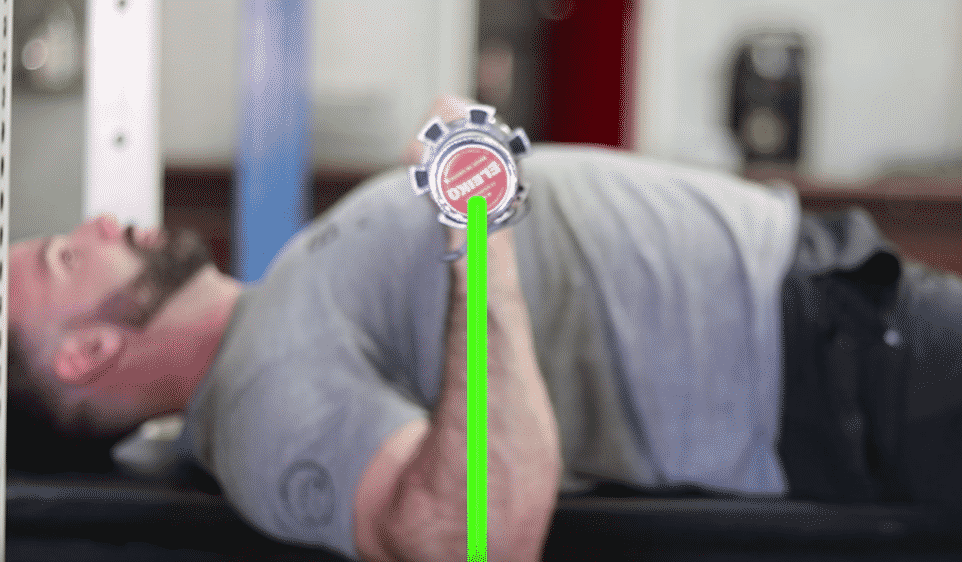

Image courtesy Barbell Medicine YouTube channel.

I hear people throw around 30-45 degrees and I don’t really have any issue with that recommendation other than it’s probably incorrect for 50% of people, though the visual imagery it produces in the lifter’s mind may be useful from a coaching standpoint.

Stemming from that point, for the general athlete trying to find their appropriate tuck form, what are some cues they can use to find consistency?

Feigenbaum: I actually don’t cue the elbow tuck unless someone is not getting it. In addition to the general bench setup, I coach the grip width and touch position and this [generally] takes care of the amount of tuck most of the time.

However, if there is too much tuck or too much flare and the width and touch point are correct, I’ll actually tell the lifter to flare or tuck their elbow, whichever is needed. I really don’t cue it outside of that—very often anyways.

Lastly—and this concept gets thrown around a lot—is there a certain point of reference athletes can use to detect when elbow flare could cause injury?

Feigenbaum: I think that we need to divorce the idea of technique error from injury or pain. Sure, it’s possible that egregious errors or some technique issue that produces acute trauma can cause an injury or pain, but the idea that a small or moderate form issue is the cause of pain or injury is a big problem in the field right now.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BhVibAMhZpM

When people hear this, they can become hyper vigilant about their technique and the joint/joints that they have some pain in, which causes them to detect pain at lower thresholds that they’d normally not even notice. It’s the pesky placebo effect rearing its ugly head.

Now, I can hear people out there screaming, “What about tendinopathies?” Yeah, what about them? They’re overuse injuries from too much fatigue being applied to a person who cannot tolerate them at that point, which is multi-factorial. It’s not a form issue most of the time.

Anyways, now that I’m climbing down from my soap box—I think the best visual reference is the vertical position of the forearm form from the front and the side. If someone can do that, then from an elbow flare position, they’ve taken care of 95% of the potential issue.

Wrapping Up

The concept of tucking and flaring the elbows in the bench press can take multiple forms in different coaches and athletes eyes. The tips above can be great tools for those who may be confused by how much they should “tuck” and “flare” their elbows in the bench press. It’s paramount to remember the fundamentals of the press, and to avoid getting wrapped up in over-analysis of details.

At the end of the day, what’s always most important is finding the form that allows you to press stronger for longer periods of time.

Feature image from Barbell Medicine YouTube channel.