When it comes to breakfast, it’s not uncommon to hear things like, “It gets your day started right,” and “It’s the most important meal of the day,” but is it? With the growing popularity of diets like Intermittent Fasting, a lot of people are choosing to ditch breakfast, while still making progress in the gym.

Why breakfast is so important makes sense in theory, breakfast is the meal we’re breaking our overnight fasts with. Strength athletes tend to feel strongly either way on the topic, pending on what they prefer. Some athletes can’t function without breakfast, others don’t eat until around lunch time, yet what does the science say?

https://www.instagram.com/p/BGqrmcFgu0L/

This article will take an unbiased look at different studies that analyze breakfast and its usefulness. Additionally, we’ll look at factors to consider if you’re thinking out making the switch from eating and not eating breakfast.

A Brief History of Breakfast

It’s difficult to find a completely straightforward background on the history of breakfast. Different societies followed different eating ideologies, which creates a scattered historical timeline of when breakfast officially became a common trend.

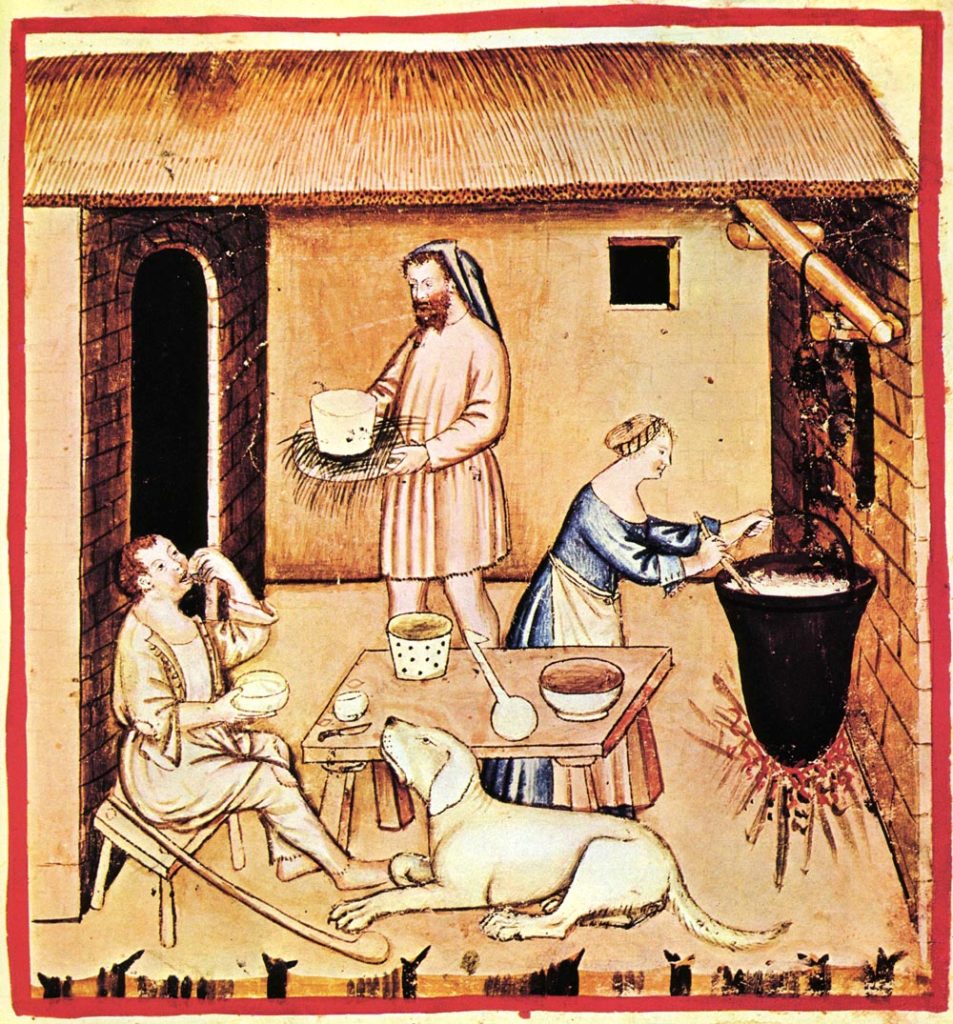

Historic literature has made connections to some societies consuming small morning meals as early as the 12th and 13th century. For example, manorial breakfasts during harvest time were documented to be composed of bread, ale, and cheese.

In the 15th century, parts of Europe didn’t consume breakfast at all. In fact, eating in the early hours of the day was said to be similar to committing the sin of gluttony. People would eat a light meal during the day, a heavier meal for supper, then often a light second supper before bed. This logic wasn’t followed by everyone at the time though, laborers, youth, elders, and sick individuals were permitted breakfast.

Photo by Sailko. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

It wasn’t until around the 16th century when breakfast became a norm for everyone, and not an exception for some, or just for the rich. Historians point out that this could be due to the reformation, greater amounts of food, and the increase in men working for others (laborers needed food for energy over long work days).

This is only a brief overview of a few historian’s perceptions on breakfast history. There are many discrepancies behind exact timelines and societies that started the trend.

Breakfast and Strength Training

There are few studies that analyze breakfast’s relationship to strength levels. This is one the areas that should be considered with an open mind, as everyone will respond different to breakfast and train at different times of the day. When you factor in training methods, training history, and goals, then this topic can become even more complicated.

[Practicing Ramadan? Check out our Lifting Guide for Strength Training During Ramadan!]

A study published in 2014 displayed a positive relationship between breakfast frequency and strength (testing grip strength). Researchers from this study analyzed 1,415 Japanese adults over the course of 2008-2011. They compared breakfast frequency, which was split into three groups (>2 days a week, 3-5 days a week, and <6 days a week).

https://www.instagram.com/p/m-RQUIKpoi/

Upon their findings, researchers noted a relationship between increased grip strength and breakfast frequency. Additionally, they noted that grip strength per one’s bodyweight was also related (aka pound for pound strength was better).

This study is interesting, but is limited in a few areas. First, it doesn’t truly apply to a strength athlete that eats consistently all of the time. For example, they used self-reported questionnaires, which fail to state if their population was always eating within the three categories. Second, their population varied and weren’t athletes (the study states employees). The way an athlete will eat and utilize strength will be different compared to most of this study’s population.

Breakfast and Cardio Respiratory Fitness

In 2010, a study analyzed 4,326 English schoolchildren’s breakfast eating habits and compared their BMI, physical activity, cardio respiratory fitness (CRF) levels. Their participants were all aged 10-16 and consisted of 2,336 boys and 1,990 girls.

For BMI, researchers had the children’s height measured and recorded them into three categories as determined by the BMI classifications. Physical activity was assessed by a questionnaire students filled out, and CRF was assessed through the use of the Pacer test (20-m shuttle runs back and fourth to the sound of a beep until students couldn’t continue).

https://www.instagram.com/p/BUucC8rDHb0/

Researchers assessed breakfast habits through the use of a questionnaire, which entailed how often students ate breakfast. Conclusions were suggested from each category based on the frequency of a student’s breakfast habits. They found that students who consistently ate breakfast had “healthier” BMIs, higher physical activity levels, and better CRF scores.

This study should also be taken with a grain of salt, because it has multiple limiting factors when applying it for strength athletes. First, BMI isn’t always an accurate assessment of who’s “healthy”, as it lacks to account for muscle. Second, these were schoolchildren (not grown athletes) filling out surveys, so accuracy of answers could definitely vary. Third, the CRF test’s results could be skewed to a child’s attitude towards the test itself.

Breakfast, Muscle Growth, and Fat Loss

When it comes to muscle growth and fat loss, breakfast as a standalone won’t impact these factors nearly as much as one’s whole diet. Basically, it’s the accumulation of eating in addition with training habits that will positively influence these the most. One area we can assess are studies that analyze health-related biomarkers without the consumption of breakfast (aka time restricted feeding studies).

[If you eat low-carb, or practice a ketogenic based diet, then check out this article covering their effectiveness for strength training!]

For example, this study from 2016 compared resistance trained athletes following a time restricted feeding (TRF) diet and a normal diet (ND). Researchers followed their study population for 8-weeks and tracked their basal metabolism, maximal strength, body composition, inflammation, and cardiovascular risk factors.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BEaiaMAB59-/

The study’s population consisted of 34 resistance trained males (split into two groups: TRF & ND) with at least 5-years of training experience. Their TRF group followed a 16-hour fasting period with an 8-hour eating period, and consumed three meals at one, four, and eight P.M (no breakfast). The normal diet followed the traditional three meal regimen of breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Individuals trained in the gym three days a week and followed training splits, which were held between 4-6 P.M (participants were allowed a protein shake ~30-min post-workout). Researchers assessed that the TRF group lost more fat over 8-weeks, but had a slight decrease in total testosterone and IGF-1 (which varied). Both groups saw strength improvements and maintained muscle mass. The TRF group also saw a decrease in blood glucose and insulin levels.

This is one of the more relatable recent studies that analyzed resistance trained individuals without the consumption of breakfast. Their research suggests that TRF can be useful for athletes who want to maintain muscle mass and lose fat. Keep in mind, this study lacks to identify long-term effects of this eating style, which they point out.

Is Breakfast Right for You?

When considering dropping breakfast and switching to some form of time restricted feeding, or just eating later in the day, then you should consider a few factors. It’s not a black and white question, and sometimes the more obvious deciding factors get overlooked in search of a perfect eating solution.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BMnO6OGDpeO/

Assuming you have your daily caloric/macronutrient goals in check (pending what you like to follow), then we can assess if eating or skipping breakfast will work best for you.

Factors to Consider

- Daily Schedule: This entails what your day-to-day looks like. What’s your work and daily schedule like? If you’re not performing optimally at work, or in other activities with a breakfast change, then chances are your training will also take a hit. Overall quality of life and daily “life” performance should be one of your top concerns, as training is usually only a small increment of your day.

- Training Time: When do you train during the day? This is a basic factor that often gets overlooked when searching for new diet methods. Your goal should be to promote/support training, not derail progress, this is when trial and error with breakfast eating and training times will come to play.

- Energy Levels: This applies for anyone who’s making a breakfast switch, or wants to make a switch. My advice, follow your breakfast/no-breakfast eating trial strictly for three-weeks, and try to record your energy levels three times throughout the day on a scale of 1-10. The first few days of the switch may seem easy/hard for different individuals, so consistently tracking energy levels for three-weeks can give you a good idea of what’s going work best for you long-term.

- Mood: An easily overlooked aspect for a lot of strength athletes is mood. This aspect will usually go hand-in-hand with energy levels, but can sometimes vary. For mood, you can make daily notes similar to how you’d record energy levels. If you find your mood changing in the morning hours without breakfast, then you may want to consider a slight change to counter this.

Breakfast and Vegetarian Athletes

Athletes who follow a vegetarian diet and are experimenting with breakfast eating/skipping will follow similar methods as athletes who follow a “standard” diet. A few considerations vegetarians should keep in mind is where they’re going to make up the macro and micronutrients they may be missing in their first meal.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BUvw7CNhH1R/

These athletes will more than likely have to spend a little more time working out the manipulation of their following meal compositions to achieve their daily nutrient goals. If you follow a vegetarian diet, then you’ll already most likely be well aware of this aspect.

Breakfast, Strength Training, and the Paleo Diet

Athletes who follow a paleo, or paleo-esque diet will have to account for similar considerations as the vegetarian athlete. This diet form will entail some strategy behind meal choices, because it’s a little more limited, and will be heavily dependent on what foods fall into your “paleo” diet category.

[Need a little paleo and vegetarian meal inspiration? Check out our review of the popular Trifecta Nutrition meal delivery service.]

Possibly the biggest concern for paleo eaters is maintaining their energy levels throughout the day with the foods included in their diet.

Closing Remarks

The studies included above are not an end all be all when it comes to breakfast’s relationship to strength, cardio performance, muscle growth, and fat loss. Research continues to grow around this topic and demographic (strength athlete), so there isn’t a definitive answer on whether breakfast is a must or not for strength athletes.

While research is back and forth on the topic of breakfast being a must, the way we eat to influence our training goals are not. Judge your breakfast consumption off of your training goals, daily schedules, and overall quality of life. Like Intermittent Fasting, both eating and not eating breakfast isn’t for everyone, and you should make an educated decision based on your diet allowances, training performance, and quality of life.

If you’re interested in making the switch between eating and not eating breakfast, then give the transition time (2-3 weeks), and try to be adamant in tracking multiple factors like training progress, energy levels, and overall moods.

Nutrition coach and Certified PT Megan Flanagan had this to add regarding the differentiation between breakfast and pre-workout nutrition, but emphasizes this can vary from person to person.

“Although I believe the choice of whether or not and what to eat for breakfast depends on the individual, I would emphasize the importance of getting some kind of fuel in your system before a workout, whether it’s half a banana, a slice of peanut butter toast, a few sips of a sports drink or a full breakfast a few hours before.

As an athlete who often works out first thing in the morning, I think of my breakfast as two parts: a small something beforehand, even if it’s just a piece of fruit or half a granola bar and refuel with a protein-rich breakfast after (such as an egg scramble with veggies, toast with peanut butter, greek yogurt, and coffee). I always feel better when I have something to eat in the morning and notice that my personal training clients tend to, as well.”

Feature image screenshot from @a_madteaparty Instagram page.