Post-Activation Potentiation (PAP) is a training concept used by strength and conditioning coaches when the goal is increasing force output and rate of force development.

Generally, the methodology behind PAP is reserved for trained individuals with a very specific performance goal. In recent years, more research has highlighted the usefulness of PAP training and how to use it properly, which was the inspiration behind this article. This isn’t to say that coaches have been using PAP training wrong, however, newer research has suggested interesting ways to use it to improve power production.

Author’s Note: This article is an update to my previous PAP TRAINING ARTICLE which was written for BarBend in 2016. In the last two years, research has expanded on this topic [PAP] and I’ve changed some of my coaching rationales and styles to accommodate for these changes.

In this article, we’re going to cover four Post-Activation Potentiation topics including,

- What is PAP? How does it work?

- Current concepts used and rationale behind them.

- PAP training revisited.

- Potential methods worth trying.

What Is PAP?

PAP training is a self-induced conditioning contraction at a near-maximal or maximal load that has been shown to consistently increase contractility properties of the muscles being trained during successive contractions. In layman’s terms, PAP is a loaded, often compound movement, followed by an explosive, plyometric-based movement with the goal of improving power.

In practice, PAP will usually take form as a compound movement coupled with a plyometric exercise, which makes up a traditional superset.

The theory behind PAP basically suggests that as the body is loaded with varied intensities it becomes “primed” to produce higher rates of force after the loading due to the increased demands on the body. If you’re still having trouble relating this to your own experiences, think about this:

Remember the last time you squatted or deadlifted heavy and the first set felt slow, but by the second and third set the weight actually felt lighter and moved better. This is similar to what PAP training suggests and tried to capitalize on.

More than likely, as you progressed through your sets, your body’s nervous system, musculature, and joints became better suited to move the weight efficiently: if you place a high demand on the body, then it will super-compensate and create an equal or higher stress response for the sets to come. This super-compensation is essentially what PAP tries to capitalize on, but what exactly is going on in the body during PAP style training?

There isn’t a definitive answer on this exact question, however, research has suggested three potential reasons why PAP works the way it does and these include (1),

- Phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chains

- Increased recruitment of higher order motor units

- Possible change in pennation angle

All three of these characteristics can play a role in force development, and more specifically in PAP training.

Phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chains have been suggested to play a role in the molecular memory of subsequent muscle activation and contractions (2). Increased recruitment of motor units can play a role in the potential for overall force production (3). Muscular pennation angle can play a role in suggesting how much force a body part/muscle can produce (4).

More than likely, each of these mechanisms are at play to some degree during PAP training, as they all play a role in how our body produces force. However, until more research is performed on this topic, we can only make our best suggestions as to what exactly is contributing to why PAP training works.

The Problems With Typical PAP Training

If you search around the never-ending landscape of the internet, then you’ll find multiple ways to format PAP training. One of the more traditional ways coaches have athletes train for PAP is by having them perform a near maximal compound movement, then quickly transition into a plyometric exercise with about 15-seconds of rest. This way of training needs to be revisited.

This style of PAP training can be limiting for two specific reasons.

- First, after a loaded set, there will always be a varied level of fatigue and if an athlete’s level of fatigue is higher than their ability to perform at peak levels (falling below the fatigue curve), then they won’t achieve the full benefits of the set/adaptation. Basically, if you’re too fatigued after the first movement, then your second movement’s potential will suffer.

- Second, it’s incredibly hard to know how much intensity would be the perfect amount for various athletes with this small rest time due to differences in training age, history, and so forth. Thus, it’s not an effective means for prescribing PAP for a majority of athletes.

Generally speaking, the main reason for this style of PAP training is due to time constraints. Coaches working with multiple athletes at a time need to get athletes in and out of the gym, so limiting rest is one way coaches like to maximize their athlete-to-coach training time. After all, most coaches don’t have 3-7 minutes available for rest between each movement in PAP for every athlete. That’s not realistic.

Author’s Note: One of my main reasons for writing this article is to point out that I used to perform this format of PAP training with athletes. In fact, until a few months ago if you searched BarBend’s PAP articles, then you’d notice the above format of “lift + explosive movements that mimic it” prescribed. However since that initial PAP article, I’ve learned more and formatted PAP training slightly different.

What New(er) Research On PAP Has Uncovered

So now that we have an understanding that 15-seconds is too little of rest time for traditional PAP training, we’re left with two questions:

- What’s an ideal rest time for PAP training?

- How heavy should the initial conditioning contraction be?

There have been a couple of great studies that have highlighted ideal rest times for PAP training.

“Meta-analysis of postactivation potentiation and power: effects of conditioning activity, volume, gender, rest periods, and training status.”

The first piece of data we’ll reference in this article comes from a meta-analysis published in 2012 in the Medicine & Science In Sports & Medicine journal (5). In this meta-analysis, authors went through 32 studies that had four specific things in common:

- They had to investigate the effects of a conditioning activity on power output following a contraction.

- The contraction’s load needed to be higher than the following movement.

- No external electrical stimulus could be used during the study.

- Only human controlled random trials could be included.

This meta-analysis was great because it provided a ton of suggestions for coaches and trainers.

- The analysis included studies that included untrained, trained, and athlete populations, then identified how effective PAP training was for each.

- The analysis broke down which rest intervals tended to see the best benefit with PAP training.

- Authors compared how single sets stood up against multiple set PAP training protocols.

- The research assessed how much loading was needed to obtain the greatest PAP benefit.

Here’s what the study found

- Multiple sets with PAP training provide great benefit than a single set.

- Untrained populations don’t receive nearly the same benefit as trained and athlete populations. Athletes with over three years of training experience displayed the greatest benefit.

- Rest intervals between 3-7 minutes were generally the best for accommodating fatigue and peak performance. Athletes and trained populations aired on the lower end of this spectrum, while untrained populations required more rest to perform optimally.

- Moderate intensities for the initial conditioning contraction between 60-84% saw the greatest benefit.

Overall, this meta-analysis provides a ton of great suggestions for implementing PAP training into programs. As with every piece of research, it’s up for personal interpretation, but generally, trained individuals working with moderate loads for multiple sets reaped the most benefits with PAP training.

“Acute Effects of Back Squats on Countermovement Jump Performance Across Multiple Sets of a Contrast Training Protocol in Resistance-Trained Men.”

Another great and more recent study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research directly compared two different styles of PAP training (6). One style included moderate loading with a back squat (6 x 60% 1-RM) into a counter movement jump (CMJ), and the other used high intensity sets (4 x 90% 1-RM) into the CMJ. These two intensities were then broken down into seven different rest protocols: 15 seconds, 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 minutes.

Authors noted that both the moderate and high intensity groups displayed signs of fatigue directly following the back squats and saw the greatest benefit resting between 3-7 minutes.

This study is great for coaches and trainers for three specific reasons,

- They only used trained athletes, so their suggestions are applicable to most coaches/trainers and advanced clients, AKA the population more than likely using PAP training for benefit.

- Both moderate and high intensities back squats were useful for improving counter movement jumps. Typically, PAP training can be very demanding, so the use of moderate intensities may be useful for limiting fatigue following the acute training session.

- Rest periods were similar to the meta-analysis above with the suggestion of 3-7 minutes. However, there was a small, trivial benefit at 1-minute of rest in this study with the moderate intensity group, so this load:rest scheme may be a viable suggestion for advanced athletes on a time crunch.

Practical Takeaways From This Research

If we broke down the research referenced in this article, then we’re left with a few suggestions that we can keep in mind for PAP training’s best uses. Like with all research, it’s always up to your personal interpretation, but here are some of the takeaways that I’ve gathered from the research.

- Moderate and high intensities in the conditioning contraction work for PAP training, which is great to know because high intensity PAP training sessions can create a lot of fatigue, so it’s not always a realistic training option for athletes with busy training schedules. If athletes can obtain PAP benefits with less intensity, then this method can be used for specific goals (force development/power output) more often without as much fear around accumulation of fatigue.

- The ideal rest period tends to live between 3-7 minutes, and if an athlete has more training experience, then they can get away with less rest. Rest intervals of 1- minute may be useful for experienced athletes when using moderate intensities (=/<60% 1-RM). This is useful information for coaches who have to program PAP training for teams and know which athletes have more experience, AKA they can group them and create protocols accordingly.

- Multiple sets work best with PAP training.

New Methods of PAP Training Worth Trying

Alright, so let’s assume you’re a coach and you understand how to best program PAP, but you’re limited on time. A 3-minute rest interval is just not possible, so what can you do?

One method you can try is adding mobility, active recovery, and pre-hab movements in the prescribed rest interval time. This allows athletes to perform activities that are not incredibly demanding and are usually programmed anyways — you’re killing two birds with one stone.

Ideally, these light activities between sets will either a) help promote performance in the following sets by stimulating areas currently being worked on, or b) focus on a completely different body part to preserve overall energy. Check out some examples below!

Back Squat Example (5 x 65% 1-RM)

- Similar Intra-Set Movement: 3 minutes of rest with 60 seconds of hip internal rotations / 5 Vertical Jumps

- Different Intra-Set Movement: 3 minutes of rest with 20 Band Pull Aparts / 5 Vertical Jumps

Deadlift Example (Hed Bar Deadlift 4×80% 1-RM)

- Similar Intra-Set Movement: 3 minutes of rest with 15 reps of cat camel / 8 Triple Extension Med Ball Throws

- Different Intra-Set Movement: 3 minutes of rest with 60 seconds of foam rolling on the calves / 8 Triple Extension Med Ball Throws

Bench Press Example (4×70% 1-RM)

- Similar Intra-Set Movement: 3-minutes of rest with 20 reps of 90/90 arm sweep stretch / 5 Supine Med Ball Throws

- Different Intra-Set Movement: 3-minutes of rest with 10 light tempo goblet squats / 5 Supine Med Ball Throws

What’s most important when trying the above is to be methodical with the inter-set activity. As a coach, scale movements and reps based on your athlete’s ability to handle certain workloads; these are just loose examples above. More than likely, there’s going to be a lot of trial and error with this style of PAP training.

A couple questions worth keeping mind when programming and creating PAP training protocols include:

- Can the set be scaled and tracked?

- Does the set’s specificity align with current goals?

- Will the set cause too much fatigue for the rest of the workout?

Wrapping Up

As research improves and better methods are tested, we learn how to more effectively train in certain settings. PAP is the perfect example of an area of training and research that continues to expand and broaden. Coaches should apply the latest research with their knowledge and best practices to obtain the biggest benefit for their efforts.

References

1. D, T. (2019). Factors modulating post-activation potentiation and its effect on performance of subsequent explosive activities. – PubMed – NCBI . Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 15 August 2019, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19203135

2. Yu, H., Chakravorty, S., Song, W., & Ferenczi, M. (2016). Phosphorylation of the regulatory light chain of myosin in striated muscle: methodological perspectives. European Biophysics Journal, 45(8), 779-805. doi:10.1007/s00249-016-1128-z

3. Potvin, J., & Fuglevand, A. (2017). A motor unit-based model of muscle fatigue. PLOS Computational Biology, 13(6), e1005581. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005581

4. Sopher, R., Amis, A., Davies, D., & Jeffers, J. (2016). The influence of muscle pennation angle and cross-sectional area on contact forces in the ankle joint. The Journal Of Strain Analysis For Engineering Design, 52(1), 12-23. doi:10.1177/0309324716669250

5. Wilson JM, e. (2019). Meta-analysis of postactivation potentiation and power: effects of conditioning activity, volume, gender, rest periods, and training status. – PubMed – NCBI . Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 15 August 2019, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22580978

6. Bauer, P., Sansone, P., Mitter, B., Makivic, B., Seitz, L., & Tschan, H. (2019). Acute Effects of Back Squats on Countermovement Jump Performance Across Multiple Sets of a Contrast Training Protocol in Resistance-Trained Men. Journal Of Strength And Conditioning Research, 33(4), 995-1000. doi:10.1519/jsc.0000000000002422

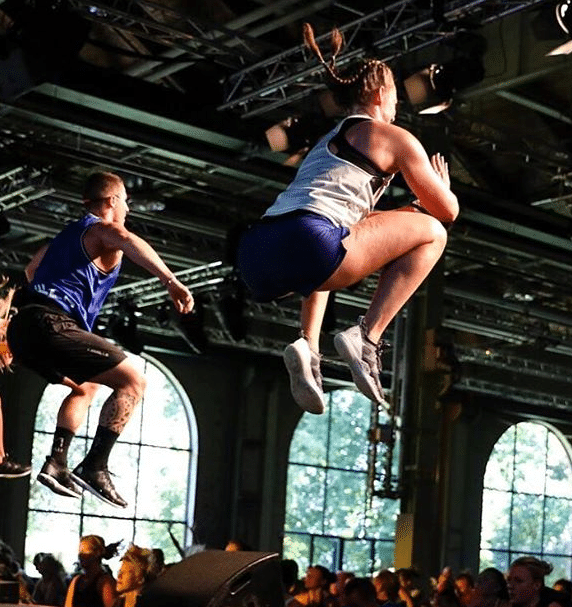

Feature image from Jacob Lund / Shutterstock.