Before reading any further, I have a confession.

The title above is a little misleading because the idea of “perfect” isn’t really achievable in strength sports and working out. Sure, we can find what’s best for us, but perfection is pretty tough to accomplish with multiple workout options, variables, and daily changes in our bodies. So while we may not be able to find perfection, we can find what’s best for us by looking at a few different criteria, and for many athlete that can be “perfect”.

Workout frequency has been and will continue to a debated topic in strength sports. After all, is there one frequency that clearly works best for a majority of athletes? It’s tough to say when we account for other workout parameters like intensity, volume, and so forth. This article will explore the research behind frequency, factors that can influence frequency, and a few pillars you can assess when finding your ideal frequency.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BfCSk-EBnc2/

High Vs. Low Workout Frequency and the Research

There have been multiple studies looking at whether higher versus lower frequency reigns as triumphant for optimal gains. They’ve suggested that both have benefit, but without a definitive winner. This is why this topic is highly debated, and various coaches continue to have split views on the topic. For this section, we’ll cover some of the most relevant studies and what they’ve suggested.

Lean Mass and Strength

This study from 2016 sought to find out whether higher or lower training frequency worked better for acquiring lean mass and strength. Researchers had 19 participants split into two groups: Low Frequency Training (LFT) and High Frequency Training (HFT) for an eight week training cycle. To assess lean muscle mass, researchers took each participant’s body fat measurements with a dual energy x-ray absorptiometry. For strength, they tested a subject’s 1-RM on the chest press and hack squat pre- and post-training protocol.

The LFT group worked out three times a week and trained agonist muscle groups once per week, so they had a chest, back, and leg focused day. For the HFT group, these members also trained three times a week, but hit full body workouts every lift, so the agonist muscle groups were being trained three times per week. Each workout, participants performed every exercise for three sets and aimed to hit 8-12 reps. Once a participant could hit 12 reps for an exercise, they’d increase the load by 3% and round to the nearest 1.3kg.

After the eight weeks, researchers found that both the HFT and LFT groups had similar pre- and post-training results. There was no significant difference between the two for lean mass. For 1-RM strength, researchers found that neither the chest press or hack squat improved over each other significantly, but the chest press did see a slightly higher improvement in the HFT group.

Muscular Adaptations – Hypertrophy

Another study worth noting is this 2015 study that was headed by Brad J. Schoenfeld assessing training frequency and muscular adaptations. For this study, researchers split 20 participants into two groups who followed a split-routine or total body workout. Researchers were interested in how muscular hypertrophy differed when volume was created equal. Participants in the split routine hit multiple exercises for 2-3 muscle groups per workout, and the total body routine trained each muscle group for one exercise once per workout.

Workout variables such as volume, exercises, and rest intervals were all held consistent for the eight-week exercise protocol. In addition, researchers advised subjects about proper dietary adherence to limit possible differences that could be caused by dietary and supplement variance. To look at muscular hypertrophy, subjects had B-mode ultrasounds performed on their forearm flexors, forearm extensors, and vastus lateralis. Strength was tested with the use of pre- and post-test 1-RM for the parallel back squat and barbell bench press.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BeqMl50HLy4/

After the completion of the eight-week workout protocol researchers noted that both the total and split-routine group saw improvements in all of their recorded muscle groups. Although, the forearm flexors saw a slightly higher improvement in the total group compared to the split-routine. For 1-RM tests, there was a slight advantage in the bench press with the total routine, but for the back squat both workout styles were nearly identical.

Researchers discussed that the trend for improvement of hypertrophy leaned towards the total group, as opposed to the split group when volume was created equal. Also, I’d suggest checking out Schoenfeld’s 2016 meta-analysis on frequency and muscular hypertrophy for further reading.

Muscular Adaptations – Strength

A study from 2000 sought out to find differences between 1-RM strength pre- and post- 12-week exercise intervention when resistance trained males trained either one or three times a week. Researchers split subjects into two groups, which either trained once a week or three times a week. The one day a week group performed an exercise for three sets to failure, while the three days a week group performed one exercise for one set to failure each workout.

To assess strength, researchers had subjects perform 1-RM tests on various upper and lower body exercises. 1-RM tests were performed pre-test, at 6-weeks, and at 12-weeks. Over the course of the 12-week exercise protocol each group saw improvements in their 1-RM strength, but the three days a week saw slightly more improvements. Additionally, researchers noted that increases in lean mass favored the higher frequency group, but these findings were relatively small.

Muscular Adaptations – Strength & Size [Untrained]

This study from 2017 analyzed the differences in muscular strength and size of the elbow flexors with training once or twice per week in untrained participants. Researchers had 30 subjects split into two groups who performed the same amount of volume during their workouts, but either trained once or twice per week. The subjects in this study didn’t have a previous resistance training history.

For the workouts subjects performed the same exercises, which consisted of lat pull-downs, seated row, barbell bench press, seated chest press, standing barbell biceps curl, Scott bench biceps curls, lying barbell, triceps extensions, and high pulley triceps extension. Upon finishing the 10-week exercise protocol, researchers investigated muscle thickness of the right arm flexors with the use of a B-mode ultrasound, along with measuring flexed arm circumference and peak torque.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BbeqHPonGGZ/

Both groups saw an improvement in muscle thickness, arm circumference, and peak torque after the 10-week intervention. However, the group that trained twice a week saw slightly more improvements for the three criteria, and improved their peak torque to a greater extent than the single session group. This would suggest that untrained individuals can improve with lower frequency training, but two days a week showed slightly higher improvements.

Volume Over Frequency?

The most relevant and recent study for strength athletes we’ll look at comes from this past January. Researchers were interested in assessing increases in maximal strength for the three powerlifts, along with body composition when athletes followed moderate and high frequency training. Subjects followed a 6-week exercise protocol and had at least 6-months of previous resistance training history.

To be included in this study, a subject needed to have a back squat of 125% of their bodyweight, a bench press of 100%, and a deadlift of 150%. For body composition, researchers had subjects use a Body-Metrix BX-2000 A-mode ultrasound to assess their fat free mass. To test 1-RM strength, researchers had subjects undergo the 1-RM protocol recommended by the National Strength and Conditioning Association, and for a lift to count it had to match the USA Powerlifting’s judging criteria for a “good lift”.

The two groups were split into a group that trained 3x a week and a group that trained 6x a week. Volume and intensity were equated to be equal, and athletes followed an undulated workout program with the utilization of auto-regulated progressive resistance exercise (APRE) to judge appropriate workout progressive overload.

Upon the completion of the study, researchers noted that both groups saw an improvement in their 1-RM back squat, bench press, deadlift, powerlifting total, Wilks Score, and improved their body composition. Researchers hypothesized that their results would reflect this, and suggested that volume may be more indicative for improvement when compared to frequency.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BfPvpEmhQIC/

Authors also discussed that while previous research has suggested that jumping from one to three days a week may show greater improvements in muscular adaptations that there may be a ceiling to frequency’s benefit, and the law of diminishing returns could be the reason for this.

However, there was a slight trend towards the 6x/week group [most for the bench press] when it came to improving 1-RM strength, so researchers also brought up that high frequency and lower volume could be beneficial, but there needs to be more research performed before drawing conclusions.

Research Takeaways

The above studies’ information are up for one’s own interpretation, and there’s really no conclusive findings that suggest higher versus lower being consistently better for maximal gains. Below are three takeaway points I noted from the research presented in this article.

- If volume and intensity are equal, then frequency may be slightly less imperative for progress compared to overall volume. The last study is possibly the most applicable for strength sports [powerlifting specifically] and it suggests a valid point by accounting for the law of diminishing returns with increase in training frequency past a certain point.

- If you’re on the newer side of lifting (<6 months or less), then frequency may be less important for growth, yet still beneficial. This was seen in the untrained study, and I would guess this is because of “newbie gains”, aka the time frame of rapid adaptation to resistance training when you begin lifting. Granted, higher frequency did see slightly better improvements, a newbie’s body will need a lower stimulus to grow, so they can get away with fewer days.

- Higher frequency tended to suggest slightly better improvements in strength, hypertrophy, and muscle size, but it shouldn’t be the only variable accounted for. If you’re training at a higher frequency, then account for things like fatigue accumulation, total volume, intensity, and other variables. For example, don’t blindly increase frequency without a periodized plan or end goal in sight.

Again, the suggestions above are how I interpreted the research, and you may very well see it differently. As strength sports continue to grow, so does the research on frequency in this field, along with over variables. Hopefully we’ll continue to see more studies performed such as the last study that’s directly applicable to sports like powerlifting.

What Can Influence Frequency

There’s no clean-cut method to find your perfect workout frequency, but there are multiple factors we can look at to try and dial in on what could be best for you. Below are a few categories and subcategories that could influence your ideal workout frequency.

Strength Sport

Depending on your strength sport, there will be some variance in how often you need to train to progress. It would be impossible for me to suggest definitive time periods without knowing your training history and sport, but below are a few subcategories you should consider.

- Type of Sport: Powerlifting, strongman, weightlifting, functional fitness, and bodybuilding will all have different demands when it comes to how often you need to train. For example, weightlifting may need a higher frequency as it’s more technical, while powerlifting may need less due to a higher fatigue factor.

- Time of Season: Are you in prep for a meet or in the off-season? The timeline of your sport’s season will play a big role in frequency. This is something your coach would assess and program accordingly for your needs, as fatigue accumulation will be highly present in some of these scenarios.

- Training Age: How long have you been in your sport? Some athletes who are further along their career may need increased frequency to match a stimulus they require to grow. On the other hand, they could also need less, as their sessions are more physically demanding. This is another consideration a coach would have to assess.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Befrvs8jC-8/

Lifestyle

It can be hard to accept, but it’s also impossible to ignore: your lifestyle can play a major role when finding your ideal workout frequency. For example, if you’re continually stressed and working long hours, but you want to train all of the time, yet you also continually feel run down, then you may need to train less often in order to progress. Below are a few lifestyle components to keep in mind for workout frequency.

- Stress Levels: I’m not going to dive too deeply into the science behind stress, increased cortisol levels, and strength training. In some respects stress is good in strength training — it’s how we grow. But too much stress can decrease adrenal stores and deplete us of energy stores like glycogen, so when you feel that stress is affecting your energy and performance, you may want to make an effort to counter it, so you can achieve your desired workout frequency .

- Time Allotment: Be honest with yourself and how much time you have to train. If you’re always pressed for time, and can’t get full programmed workouts in without rushing, then you may need to reassess how frequently you can work out.

- Sleep: Similar to stress, sleep should be taken into consideration when finding ideal workout frequency. Sleep is when we recover the most and if you’re cutting your slumber short, then you may want to train less. Research backs this up: one study concluded that athletes who slept less than eight hours per night got injured 1.7 times more often.

- Diet: This point alone isn’t going to make or break your workout frequency, but it can help when used wisely. Simply put: if you’re training more often, you’ll need to consume more food [energy] to match your output.

Workout Goals

This might be a no brainer, but a lot of athletes don’t ask themselves this question: what are your goals? When finding your ideal workout frequency your goals can play a major role in helping you decide where to start. Below are a few goals and how you might structure your frequency around them.

- Strength & Power: If your main goal is strength and power, then I’d suggest looking at two factors: Training history and fatigue. These two will play important roles in deciding what’s a realistic frequency for you. For example, someone who’s closer to their genetic potential will have to carefully decide how to match their need for higher stimulus while keeping fatigue manageable. If you’re programming your own workouts, try taking a 2-week test: if you feel completely wiped the whole workout for every workout, then you may need to dial it back.

- Cardiovascular fitness: If you’re working to improve your cardiovascular fitness, then you can most likely get away with working at higher frequencies, depending on the total volume in your program. Often with this goal you’ll be using less weight, so you can train more often without feeling drained or sacrificing form due to decrease in neural capacity.

- Hypertrophy: From the research above, both higher and lower frequencies can be beneficial for hypertrophy, but higher may be slightly better. If hypertrophy (body composition) is your main goal, then make it a point to look at volume and realistic time allotments, these two factors are going to help with achieving ample progressive overload .Also, you could account for how much training you need to simply maintain the levels you’re at. For example, Dr. Mike Israetel has made an awesome video series on this, and I’ll embed one below.

Finding What’s Best For You

Now the fun part, finding what’s the best workout frequency for you. If you’re a recreational lifter, then we can look at what organizations like the National Strength and Conditioning Association have recommended for frequency. Check out their suggestions below.

- Novice: 2-3x/Week

- Intermediate: 3 for total body training, 4 for split-routines

- Advanced: 4-6x/Week

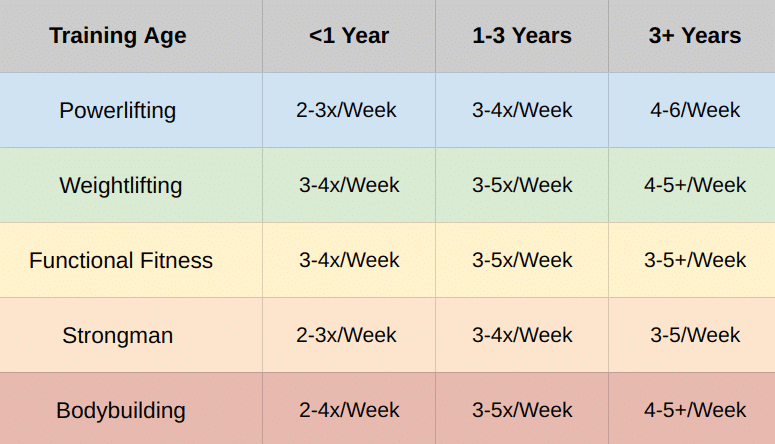

What about strength athletes in particular? Their demands will most likely be different than the recreational lifter. This being said, I’ve put together a table below that has a few suggestions when accounting for strength sport and workout frequency.

This table is based off of what’s generally implemented in each sport for an athlete’s training age, along with how long they’ve spent in that sport specifically. The timelines are sport specific, and not just time spent working out. Also, the frequencies are roughly based off of the demands a sport can impose on an athlete during their career in the respective timelines given.

Is the chart above perfect? No, that would be impossible to construct, but hopefully it can act as a starting point for some. Also, note that the chart doesn’t account for training intensities, times of season, lifestyle factors, and specific athletic needs.

Wrapping Up

The main goal of this article wasn’t to give a definitive conclusion to what frequency is best, but to present information that can help one learn how to find what’s best for them. Frequency, like every other variable in a workout, will be subject to the athlete at hand.

Is there a perfect workout frequency? Yes and no. Perfect is impossible, but there are ways to learn what’s best for you — just remember it will always be individual.

Editor’s Note: BarBend reader Shawn Parisi had the following to add after reading the above article.

“A major debate when it comes to student athletes is time spent in the gym and workout frequency.

Depending on programming, athletes can train anywhere from one to five days a week. In my opinion you ideally want to get an athlete in the gym working as much as possible while maintaining an ample amount of recovery time to which the athlete is steadily progressing weekly, monthly, seasonally, and yearly without regressing in either the gym, sport practice, and or their time on the field. In my opinion the magic numbers seem to be two to three days week. By having the two to three day workout split for student athletes it allows them to make great progress reflected in their all around performance.”