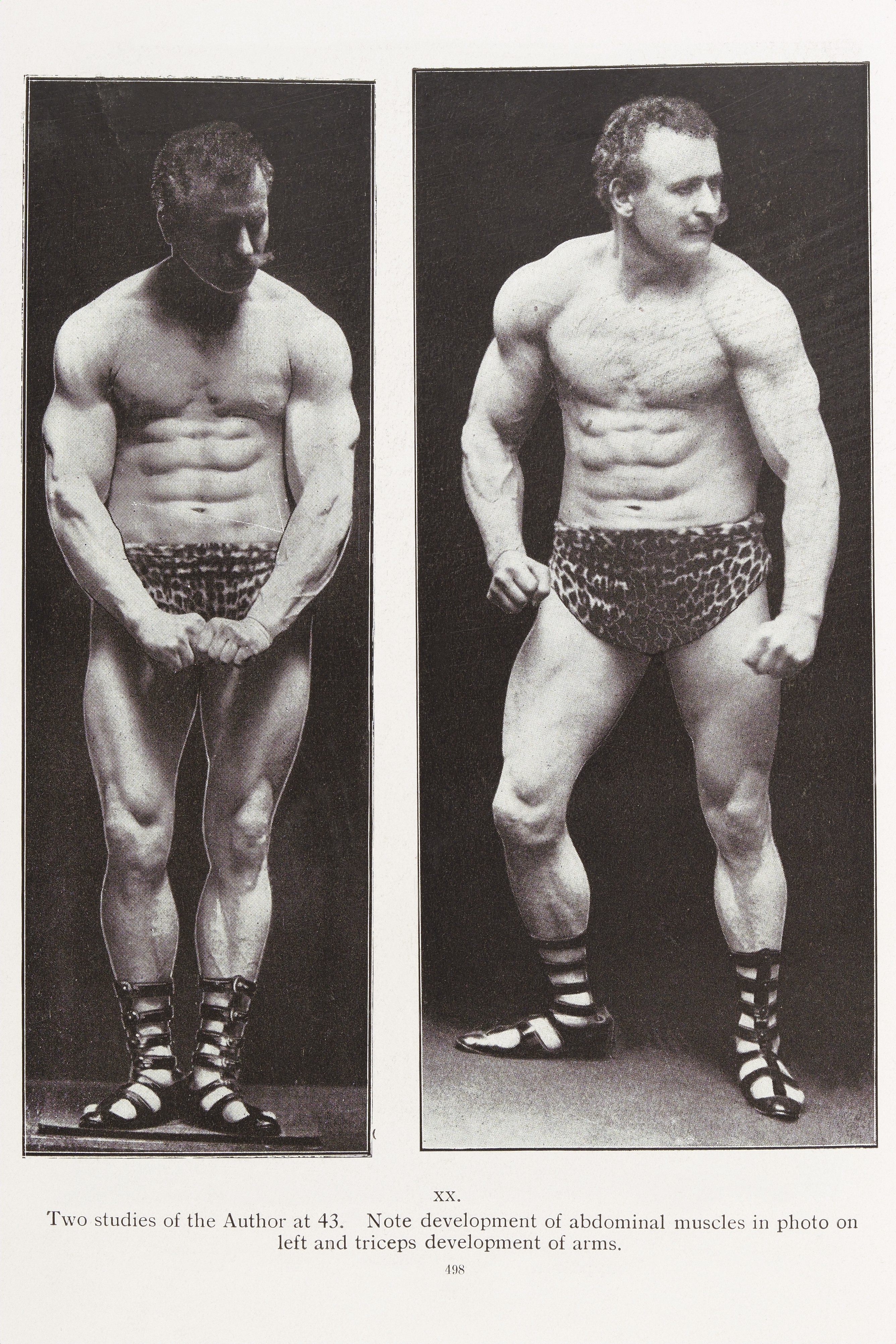

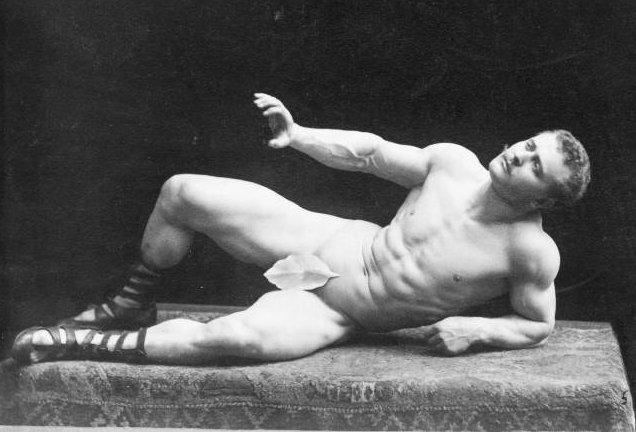

Astute fans of the Mr. Olympia contest will note that the statuette given each year resembles a stocky mustachioed man of yesteryear. The man in question is Eugen Sandow, a Prussian born physical culturist whose celebrity during the 1890s and early 1900s spread throughout much of the English and non-English speaking world.

Depicted by his biographers David Chapman and David Waller[1] as a forerunner to the modern bodybuilders of today, Sandow made the practice of weight lifting and posing acceptable for young and old during his time. As detailed by both men, Sandow’s career was truly a remarkable thing. Aside from possessing an enviable physique, Sandow went on several world tours, had his own brand of magazines, supplements, and workout devices, ran a cocoa company, trained British troops for battle, and was even appointed as a Scientific Advisor on Physical Culture to the British Monarch in the late 1910s. BarBend has called Sandow a pioneer and father of bodybuilding, and he was.

While Sandow himself is rightly seen by many as the first modern bodybuilder, he also has the distinction of being the first man to hold a recognizable physique contest. Though contests had been held before Sandow’s ‘Great Competition’ in 1901, none matched the scope or popularity of the Prussian born strongman’s venture. Thus when we speak about the first bodybuilding show in history, we’re looking directly at Eugen Sandow. This is the story of The Great Competition.

Before Sandow

As alluded to, Sandow was not the first individual to chance upon the idea of a physique contest. The idea of male beauty shows had its origins during the Greco-Roman period, a point previously noted by Crowther.[2] Though these contests were soon forgotten about by the succeeding generations, they nevertheless set a precedence for more modern approaches.

With the advent of physical culture in the late nineteenth-century, individuals became interested once more in judging male beauty. The difference this time was that beauty was defined primarily by muscularity, low body fat and visible strength. Physical culture, as previously covered on Barbend, marked a renewed interest in weight training and general ‘keep fit’ exercise during the late 1800s and early 1900s. It was a mixture of rudimentary powerlifting, bodybuilding, weightlifting, gymnastics and much more. Ben Pollack previously detailed the importance of hand balancing for these early weight training pioneers. Safe to say, they tried a bit of everything!

The holistic element of physical culture is important to note as the first recorded winner of a physique contest was Launceston Elliot, Britain’s first Olympic Gold Medallist Weightlifter. Elliot won a small physique contest held privately by a Professor John Atkinson in 1898, a year before Sandow’s own competition came to fruition.[3] While Atkinson’s contest was arguably the first physique contest held in Great Britain, which was then the bodybuilding mecca of its era, the small nature of the show and the fact that contestants were given private invitations negate any real comparison to the shows of today. Sandow’s contest on the other hand, was an altogether different affair.

[Read more: The best and worst fitness tips from old-timey bodybuilders, including Eugen Sandow.]

The ‘Great Competition’ is Born

In 1898 Sandow, whose star was still on the rise despite his already established worldwide fame, introduced fans to a rather interesting concept: a physical culture magazine. Termed Physical Culture, the periodical marked one of the first bodybuilding and weightlifting periodicals to be published monthly for a popular audience. Combining weightlifting advice with nutritional nous and fun literary stories, Physical Culture marked an intensification of Sandow’s business interests and really demonstrated his keen eye for business. [4] That the magazine ran for nearly a decade before closing is a good indication of its popularity.

Opening the first issue with the rather simple question, ‘What is Physical Culture?’ [5], the magazine soon established itself as an serious enterprise. Within months the magazine released the news that Sandow would be holding a ‘Great Competition’ [6]. This competition would seek to find the best developed man in Great Britain and Ireland. Furthermore it would hold qualifying rounds in dozens of regions around the two land masses. Unlike the ‘mass monsters’ of today, contestants were told that muscular bulk alone would not suffice. This was made abundantly clear in the first article on the topic

‘Prizes will not go to the biggest muscles but to those whose development is most symmetrical and even’ [6]

[Read More: The Most Effective Workout Splits, Created by Our Experts]

Entering the ‘Great Competition’

Becoming part of Sandow’s competition, at least in its early stages, was a rather simple thing to do. Readers of his magazine would cut out a coupon, take a photograph of themselves posing and send both to Sandow’s London offices for judgement. To win a medal in the qualifying rounds, men were graded on the following criteria

- General development

- Equality or balance of development

- The condition and tone of the tissues

- General health

- Condition of the skin [7]

Contestants were invited to enter these qualifying rounds from late 1898. Gold medallists from each region would then be invited to the grand finale to be held at a later date. While many, one presumes, competed solely for the rather prestigious sounding title of the ‘Best Developed Man in Great Britain and Ireland’, a cash incentive was also on offer.

First place would received a gold statuette of Sandow, similar to the current Mr. Olympia trophy (although the original was smaller in size, but that’s a different story for a different day). First place would also receive 1,000 guineas. Second place would receive a silver statuette and third place would receive a bronze one. The statuettes themselves were inspired by one given to Sandow by William Pomeroy during the strongman’s music hall career [8]. It is doubtful Pomeroy would have predicted the ramifications of his gift to the strongman or the sport of bodybuilding more generally.

While it was initially envisioned that the ‘Great Competition’ as Sandow titled it, would run some time in 1900, the outbreak of the Boer War in 1899 pushed the competition back. This gave Sandow’s potential competitors far more time to submit their entries. Aside from the inherent attraction that such a contest held for some, the duration of its qualifying process undoubtedly encouraged more to enter. What type of man entered the contest?

From my present research into Sandow’s Irish contestants, remember this was a contest for the best developed physique in Ireland and Great Britain, it is clear that the contestants varied in terms of religion, wealth and occupation. Thus in Ireland, one finds Roman Catholic Farmers, Church of Ireland Smiths, Church of Ireland Railway Officials and a Protestant Furrier. [9] (That’s someone who deals in fur. Simpler times.) The sheer diversity of Sandow’s contestants, at least in Ireland, showcases the broad appeal of his physique show.

[Read more: Amit Sapir’s 5 essential tips for aspiring bodybuilders today.]

The Great Spectacle…The Great Competition

After three years of adjudicating, Sandow and his fellow judges put the photographs to one side, detailed the county by county winners and announced that all first placed entrants were invited to London’s Royal Albert Hall to compete in the physical culture contest of the century. From the announcement of the date, 14 September 1901, Sandow and his team went into overdrive preparing for the event.

Competitors were told to come dressed in ‘black tights, black jockey belt and a leopard skin’ [10]. One wonders how well this costume would be received nowadays. The men were also required to meet Sandow prior to the event and choreograph their movements for the big event. Seeking to create a spectacle of unequalled proportions, wrestlers and athletes from around Great Britain were invited to compete for the audience’s amusement. Coupled with this, Sandow organized marching bands and musicians to play music supposedly penned by the Prussian himself [11]. With the preparations in place, the event went underway.

In total, sixty of Sandow’s gold medallist qualifiers competed in the Royal Albert Hall. Far from a drab affair, the theater boasted over 15,000 spectators. Needless to say given Sandow’s own success in performing, the audience were not to be disappointed. The contest opened with a musical tribute to the late US President, William McKinley, who had been assassinated the previous week. So emotive was the performance that it roused the crowd to their feet. Following this a marching performance was given by Watford Orphan Asylum before the wrestling and athletic events began.

Finally the time came for the sixty competitors to make their way to the main arena accompanied by Sandow’s song, ‘March of the Athletes’.

On the men themselves, Sandow’s magazine would later write that,

The competitors as a body were splendidly proportioned men, and it was no wonder that, despite the atmospheric conditions, the large concert hall should have attracted a crowd of all sorts and conditions of the male sex… [12]

Choosing a Winner

Dressed in black tights, black jockey belts and leopard skins, the men stood atop individual podiums. Flexing their muscles in a variety of poses, the men were expected to keep their composure as the judges moved from contestant to contestant.

Aside from Sandow, the judges that night were the sculptor Sir Charles Lawes and the doctor turned author, Dr. Arthur Conan Doyle of Sherlock Holmes fame. In the unlikely event that the men disagreed over the winner, Sandow would act as a third judge. Similar to modern shows, the great bulk of sixty contestants were cut to twelve hopeful physical culturists. From them, one man would be chosen.

At the intermission, Sandow gave his own posing display, thereby demonstrating his own credentials in this regard. When the Prussian was fully attired once more, the time came to announce the eventual winner.

[Read more from the author: The Untold History of the Back Squat.]

Bodybuilding’s First Champion

Having gone through an arduous three year wait, the time finally came to announce the ‘Best Developed Man in Great Britain and Ireland’. Beating A.C. Smythe of Middlesex who came third and D. Cooper who came second was William Murray of Nottingham. Judged to have had the finest physique across the British Isles, Murray was awarded the Sandow Statuette. [13]

For the next several years Murray toured Ireland and Great Britain performing his own posing routines. Sandow continued to go from strength to strength until the outbreak of the Great War put paid to his financial successes. The sport of bodybuilding or physique contests had been born. Sandow would continue to hold physique contests in his magazine until the periodical’s closure in 1907, and American physical culturist Bernarr MacFadden held a similar competition in 1903 while countless other physical culturists recognized the value of holding physique contests. Despite a brief lull in the 1910s, recognizable shows emerged in the following decades such as the Mr. America, the Mr. Universe and of course, the Mr. Olympia.

An example of the continuity between Sandow’s ‘Great Competition’ and the Mr. Olympia contest in particular can be found in the latter’s trophy given out each year. In 1977, the original bronze Sandow trophy was given to the Mr. Olympia Champion, Frank Zane. Prior to this, the trophy had been in the hands of Steve Reeves, who was awarded the trophy in 1950 following his victory in that year’s Mr. Universe contest. Whose idea it was to resurrect the Sandow trophy for the Olympia is contentious as Joe Weider, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Jim Lorimer have all claimed credit at various moments. Regardless of who devised this idea, the fact that Sandow’s trophy was used demonstrates the lasting effects of his ‘Great Competition.’ [14]

References

- Chapman, David L. Sandow the magnificent: Eugen Sandow and the beginnings of bodybuilding. Vol. 114. University of Illinois Press, 1994; Waller, David. The Perfect Man: The Muscular Life and Times of Eugen Sandow, Victorian Strongman. Victorian Secrets, 2011.

- Crowther, Nigel B. “Male Beauty» contests in Greece: The Euandria and Euexia,” L’antiquité classique (1985), pp. 285-291.

- Webster, David and Doug Gillon, Barbells and Beefcake: Illustrated History of Bodybuilding (1979), p. 36.

- Scott, Patrick, ‘Body-Building and Empire-Building: George Douglas Brown, the South African War, and Sandow’s Magazine of Physical Culture’ in Victorian Periodicals Review, xli, no. 1 (2008), pp. 78-94.

- ‘Physical Culture: What is it?’, Physical Culture, 1:1, July (1898), 2-7

- ‘The Great Competition’, Physical Culture, 1:1, July (1898), 79-80

- Liokaftos, Dimitris. A genealogy of male bodybuilding: from classical to freaky. Vol. 71. Taylor & Francis, 2017, 57.

- Roach, Randy. “Muscle, Smoke & Mirrors, Vol.” Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse (2008), 28.

- This information is based on the final contestant list printed in ‘The Great Competition’, Sandow’s Magazine of Physical Culture, Vol. VII, July to December (1901), [London: Harrison & Sons, 1901), 207-213. The men’s professions are taken from the 1901 Census of Ireland available online.

- ‘The Great Competition’, Sandow’s Magazine of Physical Culture, Vol. VII, July to December (1901), [London: Harrison & Sons, 1901), 207-213

- Chapman, David L. Sandow the magnificent: Eugen Sandow and the beginnings of bodybuilding. Vol. 114. University of Illinois Press, 1994, 132.

- ‘The Great Competition’, Sandow’s Magazine of Physical Culture, Vol. IV, January to June (1900), [London: Harrison & Sons, 1900), 88-95

- Fair, John D. Mr. America: The tragic history of a bodybuilding icon. University of Texas Press, 2015.

- Roach, Randy. “Muscle, Smoke & Mirrors, Vol.” Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse (2011), 132.

Featured image via @engraved_in_iron on Instagram.