The problem with kettlebell history is that surprisingly few people care.

“Let’s say you’re a baseball fan. You play recreationally, you know who Babe Ruth is, you know the different stadiums. But in physical fitness culture, people almost never know anything about the history! Maybe they know who Sandow is, but that’s it.”

That’s Victoria Felkar, a sociocultural sports historian who’s completing a PhD at the University of British Columbia on historical perceptions of the muscular body. (Her master’s thesis was on the rise of prison weightlifting. Cool job, right?) She also has a side project that seeks to answer the question that keeps her up at night: why did the kettlebell suddenly explode in popularity in 21st century America?

Fitness historian, PhD candidate, trainer, and all-round badass Victoria Felkar.

If you’re a fan of kettlebells, you probably have a two-word answer: Pavel, duh. Pavel Tsatsouline is widely credited as the first man to popularize kettlebells in the United States after the former Soviet Special Forces trainer migrated from Belarus in the late 90s.

That’s wrong. That’s all wrong. And in her quest to uncover the secret history of the kettlebell, Felkar, along with some of her colleagues, has journeyed to archives all over the world and traveled back in time (uh, metaphorically) to old-timey Scotland, Russia, China, Germany, and America itself – about a hundred years before Pavel even landed on its shores.

So, what’s up with kettlebells?

A haltere, one of the kettlebell’s ancestors.

Image by Portum, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

A What?

The first roadblock to answering Felkar’s question is that kettlebells are little more than a weight with a handle on top. That is, intuitively, a pretty useful strength tool, which means that a lot of societies, from Shaolin monks in China to Highland Game athletes in Scotland, have produced some variation on the model, sometimes under names like “ring-handled weight” and “stone padlock.”

Even today, there are competition kettlebells, mainstream kettlebells, monkey-faced Onnit kettlebells, and more variations that some purists would never call a kettlebell.

“Suggestions have been made that in Western civilization, objects resembling kettlebells were used as far back as classical Greece,” she writes in her currently unpublished paper on the topic:

According to (historian and powerlifter) Jan Todd,¹ ² by the fifth century B.C. the ancient Greeks had developed three different weighted implements, including an object called the ‘haltere.’ Although Todd notes that there was vast variation in their appearance and composition, some of the described movements of this ‘swingable’ weight are akin to today’s kettlebell.

“The kettlebell’s a vastly unknown and unappreciated weightlifting object,” Felkar tells BarBend. “It’s a tool, it’s an apparatus, it can be used in competition and in performance. You have the blending of not only various locations using the bell around the world, but then you also have modifications on it.”

From Russia, With Love

Usually, its modern popularity gets traced to Russia, where it’s called the giro or girya. That term first appeared in Russian dictionaries in 1704 and originates from the Persian word gerani, meaning “difficult.” It’s also been traced to the ancient Slavic word gur, which means “bubble.” ³ ⁴

The story goes that Russian farmers used kettlebells as counterweights to measure out grain at the market. As bored farmers learned the weights could be heaved and tossed in feats of strength and endurance, giros began enjoying a central role in farming festivals.

Some time around the turn of the nineteenth century, a Russian doctor called Vladislav Krayevsky realized that the kettlebell deserved a place in sports medicine. Krayevsky (also called von Krayeski, Kraevskogo, and Krajewski) happened to be the personal physician of the Russian czar, who popularized kettlebell training in the Russian army which eventually elevated it to a national sport.⁵ ⁶

But that’s not the whole story. As historians unearth more and more documents, some of which can be found in archives like those at The Stark Center in Austin and The Open Source Physical Culture Library, it has become clear that kettlebells had a presence in more places than Russia.

“There are photographs of strongwomen and men prior to the 1900s who used kettlebells in feats like the bent arm press and extended lateral isometric holds,” Felkar explains, pointing to an old image of strongwoman Elise Serafin Luftmann as an example.

And importantly, many of these old images came out of Germany, which has a largely unrecognized history of using the tool. There’s even some evidence that it was the first place, or one of the first places, where the kettlebell was used as a part of physical fitness culture and strongman routines. The kettlebell isn’t purely Russian after all.

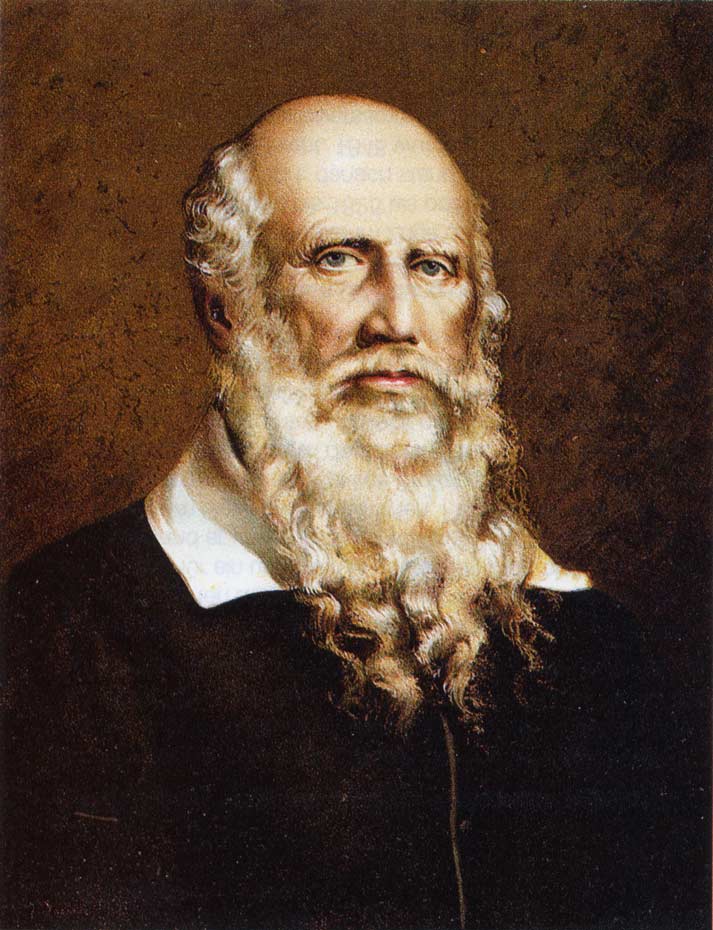

Friedrich Ludwig Jahn was known as “Turnsvater Jahn,” meaning “father of gymnastics.”

“There are tons of German training manuals and diaries and stuff like that from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that feature the kettlebell, though often under different names,” says Felkar. “Take the Turners System of Gymnastics, created by Friedrich Ludwig Jahn. He was the German physical educator who kind of created this gymnastics system that really is the hallmark of the physical education programs that we have in America today. And there are early photographs of his disciples using kettlebells.”

Since much of the Turners System is akin to the exercise programs used in CrossFit, Felkar jokes that these photographs of Greg Glassman’s ancestral father pioneering kettlebell training are “a CrossFitter’s wet dream.”

Of course it’s possible, even likely, that other countries were using weights like kettlebells at this time. But Germany, with its rich history of physical culturists and bodybuilding, is the place that has the historical documentation. (Felkar can name at least nine journals, diaries, and articles from this time that describe it.)5 7 8 9

The late 19th century was also the dawn of globalization in terms of international travel and cultural influence. There’s a good chance that it was at an 1898 gathering of strongmen in Vienna where Dr. Krayevsky became more familiar with the kettlebell as a strength and conditioning tool, after he met with the innovative German trainer, Theodore Siebert.9 12 (Heavy kettlebell swings were staples in his programs.) The czar’s physician may have then brought the idea back to his homeland, where he wrote his first book on the topic just two years later. (Felkar notes that while she likes this theory, it needs more research.)

It was also at this time that circus strongmen journeyed to and sometimes settled in America, opening gyms and giving the United States their first taste of kettlebell training. Then sometime between the 1940s and 1950s, without any explanation, it disappeared from American gyms without a trace. No one can figure out why.

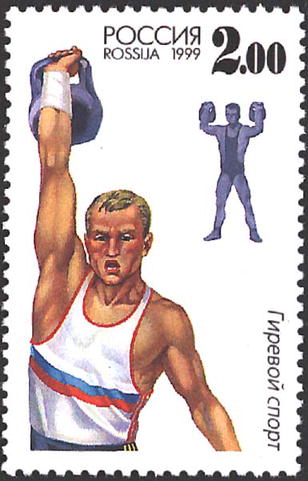

Russian stamp featuring the kettlebell biathlon

The Dawn of Kettlebells as a Sport

Theories as to the kettlebell’s disappearance range from war-born distaste for Russian artifacts to an expansive feud between two rival fitness moguls. (For history buffs, we’re talking about Joe Weider and Bob Hoffman – almost every gym had to pick a side, and neither of their training systems included kettlebells.) Of course, there’s also a chance the craze simply died out, like chest expanders or aerobics.

But in Mother Russia, the kettlebell craze was alive and well in the mid-20th century. The czar’s taste for giros had long since spread from the Russian army to the nation at large, and it was here kettlebells became not just a conditioning tool, but a sport. It was the biggest thing to happen to kettlebells since the first swing.

German sociologist Norbert Elias more or less defined the point at which activity becomes sport, contending that sports are modern cultural creations, determined by urban space, configured as commercial spectacle, and subject to formal regulations and sanctioned by public instititutions.

Kettlebell swinging and juggling was a popular “folk exercise” among Russian farming communities in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but it wasn’t until 1948 that it became an official sport.

That was the year that Russia, then the Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, declined to attend the Summer Olympics in London, declared kettlebell lifting as their national sport, and held the the All-Soviet Union Competition of Strongman in Moscow. Kettlebell contestants performed in two events: the “long jerk,” which is a clean and jerk with two bells, and the “biathlon,” which is a set of jerks with two bells followed by a set of snatches.

Throughout the 1950s, 60s and 70s, sports schools appeared throughout the Soviet Union and it became known as the “working man’s sport,” due to its inexpensive equipment and minimal space requirements. In 1981, The Official Kettlebell Commission was formed, which advocated (but didn’t enforce) mandatory kettlebell training for all workers. This, they said, would bring about a fitter population with higher productivity and a cheaper healthcare bill. 13 14 But different Soviet states tended to have different rules, weights, dimensions, and training styles. It wasn’t until 1985 that the sport was modernized and formalized across the entire Soviet Union.

“That was when the sport was shortened to ten minutes per exercise for as many reps as possible,” says Steve Cotter, founder of the International Kettlebell and Fitness Federation. “In the biathlon, you’d get one set of jerks and one set of snatches, and once you picked up the bell you absolutely could not put it down. But contestants were able to rest up to an hour between the two sets.”

Kettlebells for Fitness: A Different Bellgame

At this point, kettlebells were a fully-fledged sport in the old USSR, but implementing them for fitness – not for performance, but for wellness, rehabilitation, a healthier heart, and so on – has an entirely different motivation and practice.

“When we say kettlebells for fitness, we mean people are using them to get in shape but not necessarily competing in a kettlebell sport,” says Cotter. “In the sport you’re doing many, many reps, one to two hundred without stopping. Fitness has a different energy system and a different mindset.”

Cotter and others credit the spread of kettlebells as a sport to Valery Fedorenko, a world champion from Kyrgyzstan who migrated to America, taught the sport, and founded the World Kettlebell Club in 2006.

But then there’s the question of Felkar’s research paper: why did Americans start using kettlebells as a tool for fitness? Why did gyms start carrying kettlebells after decades without them?

Usually, the credit goes to the Belarusian Pavel Tsatsouline, a former trainer of Soviet Special Forces soldiers. Pavel is now the chairman of StrongFirst, Inc. and a subject matter expert to the US Marine Corps, the US Secret Service, and the US Navy SEALs.

“The origin of kettlebells for fitness was about the year 2001, that was when Pavel started (the certification course) the Russian Kettlebell Challenge,” says Cotter. “The marketing used with that is what first started this kettlebell fitness phenomenon that we’re still experiencing today.”

Felkar more or less agrees that Pavel’s marketing was extremely influential in spreading kettlebells as a fitness tool. She likens him to Eugen Sandow: he wasn’t the first guy to excel at bodybuilding, but he was a marketing genius who lay a lot of the groundwork for today’s world.

But as an academic, she’s not completely satisfied that Pavel is patient zero for the 21st century’s kettlebell epidemic. She points out that scores of ex-Soviet kettlebell athletes fled to America and opened gyms after the Berlin wall fell. There are more libraries for her to visit, archives to examine, stories to tell. She’ll call us when she unearths enough data to answer her thesis question more definitively.

The future of the history of kettlebells is in her hands.

Wrapping Up

“The kettlebell has a long and complex history that ultimately parallels the embodied practices of weightlifting itself. You have multiple origins, names, figures, and ways to lift the object itself,” she says. “War, global politics, globalization, the multicultural climate of North America. There are so many factors that have influenced the rise of not only physical culture, but weightlifting, all the way down to the kettlebell itself.”

It can’t even be said that the tool is from Russia, or Germany, because there’s nothing absolute about weightlifting. The kettlebell is at the center of an inconceivably vast network of international and intercultural influences and practices. It’s a riddle with a handle.

“There are so many variables involved,” she concludes. “And because it’s so complicated and messy, the average joe blogger doesn’t want to get their hands wet.”

But there are things we do know: the kettlebell came to America long before Pavel Tsatsouline, and its modern sport may have originated in Germany, not Russia. That flies in the face of a lot of conventional wisdom about the kettlebell. But hey, at least you got your hands wet.

Featured image courtesy @Strongfirst.

Bibliography

1. Jan Todd. “From Milo to Milo: A History of Barbells, Dumbells, and Indian Clubs“. Iron Games History 3 (6) 1995: 4-16.

2. Jan Todd. “Physical Culture and the Body Beautiful. Purposive Exercise in the Lives of American Women 1800-1875”. Mercer University Press, Macon, Georgia, 1998.

3. International Union of Kettlebell Lifting (IUKL). “The History of Kettlebell Lifting: From history of origin and development of kettlebell sport”. International Union of Kettlebell Lifting.

4. Andrew Volgograd. “History of Kettlebell Lifting” (translated document), http://girevoj.narod.ru/histori.html. History prepared from the Russian text “Girevoy Sport” by V. Polyakov and VI Voropaev, 1988.

5. Jurgen Giessing & Jan Todd. “The Origins of German Bodybuilding: 1790-1970,” Iron Game History 9, no. 2. 2005: 8-16.

6. International Union of Kettlebell Lifting (IUKL). “The History of Kettlebell Lifting: From history of origin and development of kettlebell sport“. International Union of Kettlebell Lifting.

7. David P. Willoughby. “The Super-Athletes: a Record of the Limits of Human Strength, Speed, and Stamina.” 1970. South Brunswick : A.S. Barnes.

8. Kimberly Ayn Beckwith & Jan Todd. “Requiem for a strongman: Reassessing the career of Professor Louis Attila,” Iron Game History 7, no. 2 -3 (2002): 43.

9. Bernd Wedemeyer (Translated by David Chapman). “The Father of Athletics, Theodor Siebert (1866-1961): A Life Amongst Bodybuilding, Life Reform and Esoterica”, Iron Game History 6, no. 3. 2000: 5.