There’s an old Hungarian proverb that goes, “A man with one ass can’t ride two horses.”

If you want to be great at something, don’t try to be great at anything else – pick a goal and focus. Ride one horse.

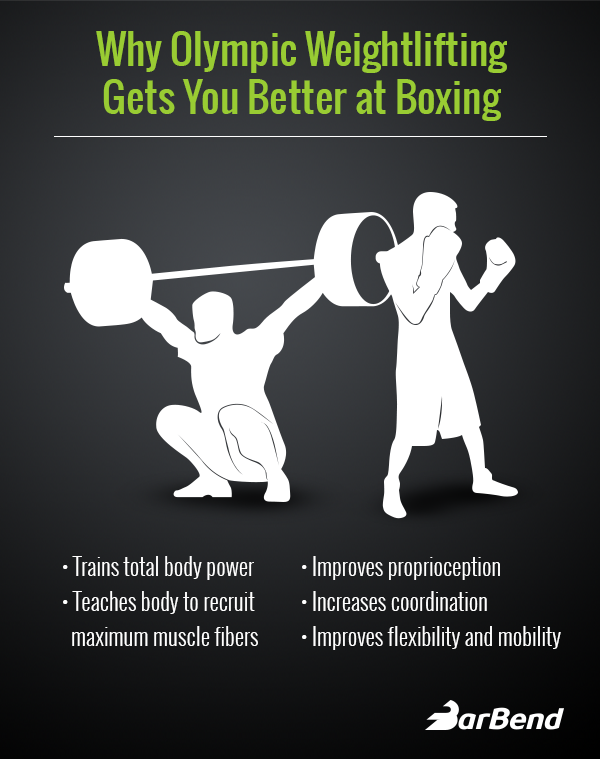

That’s often true for sports but in some cases, combing different specialties can lead to a better, more effective athlete, and that’s especially true for boxers who take up Olympic weightlifting.

“Olympic lifting is simply one of the best ways to train power,” says Rob Sulaver, CSCS, CEO of Bandana Training and founding trainer of Rumble Boxing. “It goes without saying that boxers are and need to be some of the most powerful athletes on the planet. That makes Olympic lifting incredibly valuable for boxers and combat athletes.”

“A lot of strength coaches don’t have a lot of experience with Olympic lifting so there’s some fear around it,” he says. “There’s a learning curve to it because it’s a very technical sport. If an athlete isn’t very comfortable with the lifts and their fight is coming up shortly, trying to teach them probably isn’t the best idea. But if you have a long enough training period, Olympic lifting is absolutely invaluable.”

Integrating Olympic Weightlifting and Boxing

Whether you’re training for a fight, for self defense, or for fitness, it’s useful (and more interesting) to train in blocks that focus on one specific adaptation: say, a month on power development, a month on traditional strength, a month on metabolic conditioning, and eventually circling back to Olympic lifting.

Sulaver points out for many boxers and combat athletes (he was a competitive wrestler for many years), programming tends to be skewed more toward the metabolic and conditioning side of fitness, which he feels is not the best use of time in the weight room. In his opinion, conditioning and weight management work can take place within the sport and the weights room should be for power development, absolute strength, and prehab.

To that end, if an athlete likes to train six days a week, he’ll separate the sessions into lifting days and days that focus on skill and conditioning, which might include mit work, agility, heavy bag work, and the technical aspects of putting together a boxing combination.

Here, we’re looking at a person with at least a couple of months to become as well-rounded a boxer as possible. That involves a strong focus on full-body power, and that means Olympic weightlifting. Here’s Sulaver’s ideal program for a one-month block of power training.

The Program

Monday: Snatch, followed by supplemental exercises

Tuesday: Skill and conditioning

Wednesday: Clean, followed by supplemental exercises

Thursday: Skill and conditioning

Friday: Jerk, followed by supplemental exercises

Saturday: Skill and conditioning

Sunday: Rest

No time to train six days a week? A four-day approach would combine the clean & jerk and remove a skill and conditioning session to look more like this:

Monday: Snatch, followed by supplemental exercises

Tuesday: Skill and conditioning

Wednesday: Rest

Thursday: Clean & jerk, followed by supplemental exercises

Friday: Skill and conditioning

Saturday: Rest

Sunday: Rest

For weight selection, Sulaver emphasizes that the point is to get stronger and more powerful, not to completely gas yourself on every lift.

“You’re not always working at your maximum weight, but you’re often working at a high percentage of your maximum,” he says. “Generally speaking, for more advanced athletes, intensity — as in percentage of your maximum — is pretty high. For newer athletes, I’d suggest not pushing the weight a lot until they get comfortable with the lifts. If you push too fast too soon, you screw up your form. You’ve got to be smart about it.”

The Takeaway

Working directly with a boxing coach is obviously the best way to be as fierce and effective as possible, but since it can be financially draining for people with no intention to go pro, it’s worth looking into group boxing classes like Rumble.

For functional fitness, power, balance, coordination, and confidence, both boxing and Olympic weightlifting are excellent sports. For boxers, intelligently combining the two will yield results that are far superior to only training technique and basic resistance training.

Featured image via @bandanatraining on Instagram.

Editor’s Note: Rich Considine, Strength and Conditioning Coach at Body Shot Boxing Club and BarBend reader, had the following reaction after reading the above article:

“No two fighters are the same, and neither is their preparation for a fight. At the beginning of each camp, a risk vs. reward analysis is carefully completed. As Rob points out, Olympic lifting is a very technical sport which raises the risk significantly. For boxers, the shoulder joints are their bread and butter, equivalent to a pitcher’s arm in baseball or a kicker’s leg in football. Unfortunately, Olympic lifting stresses the shoulder joints. However, the goal of training is to maximize power and sustain its output for the duration of the fight. Most importantly, Olympic lifting generates extremely valuable power which dramatically increases the reward too.”