Editor’s note: The content on BarBend is meant to be informative in nature, but it should not be taken as medical advice. The opinions and articles on this site are not intended for use as diagnosis, prevention, and/or treatment of health problems. If you’re experiencing pain or other symptoms, please consult a medical professional.

It doesn’t matter if you’re a weightlifter, powerlifter, CrossFit® athlete, or you just like to squat heavy. If you like to squat heavy, there’s a pretty good chance that at some point, your knees have started to cave inward on the ascent.

It’s common, but it can have disastrous results, sometimes causing snapped tendons and even complete knee replacements. But usually it’s not the kind of problem that causes an automatic, acute injury. Instead, it creates small imbalances at the knee every time it tracks incorrectly, wearing away knee cartilage and eventually causing pain and immobility.

“Ideally, knees should track up and down the exact same way, just like a hinge opening and shutting,” says Dr. Aaron Horschig, a sports and orthopedic physical therapist, USAW Olympic weightlifter, and founder of Squat University. “Open it cleanly, the hinge opens nice and smoothly. As you as you get a bit of knee waiver, it’s like trying to open the door but simultaneously pulling up as you’re pulling out. You can only do that so many times before the hinge starts to wear out.”

So what are the causes, and what can we do about it?

Why Do My Knees Cave In When I Squat?

The knee is basically a hinge joint that’s stuck between two other joints that control it: the hip joint and the ankle joint. While we’re most mechanically efficient when the knees track over the feet, poor hip or ankle mobility can cause pretty significant restrictions on the way down to a squat.

“It reaches a point where there are two paths the body can take,” says Horschig. “Either the knee will collapse, or the chest is going to start collapsing because the knee has stopped moving forward, meaning the hips will try to push forward instead and the chest will collapse as compensation.”

When screening ankle mobility, he likes to administer the 5-inch wall test: can you touch the knee to the wall at a distance of five inches? If so, then ankle mobility probably isn’t your problem.

So mobility can be an issue, but usually it isn’t, particularly if you’ve been training for a while and don’t have old ankle injuries giving you problems.

If your knees cave in a little when you squat, does it happen on the descent of the squat? Does it happen when you’re using light weight? If not, it’s probably more of a coordination problem than a mobility problem.

“It’s not because they’re weak, necessarily, it’s because the timing of when the muscles activate is a little off,” says Horschig. “That can be either due to fatigue or neuromuscular control issues — you haven’t been primed to move that way every single time you squat, and when you get up to very heavy weights, the body can’t properly meet the demands of that increased weight.”

Basically, it’s harder for the body to squat heavy than it is to squat light. (Crazy, right?) That means the heavier the weight, the more neuromuscular control and coordination your body needs to maintain correct form and avoid knee valgus. For a lot of us, form starts to break down as the weight gets heavier, so how do you train the system to not do that?

https://www.instagram.com/p/BWvuD1DFSvy

How Do I Stop My Knees Caving In When I Squat?

If your knees cave a little bit but they don’t go further than your big toe, it’s not such a big deal. It’s not great, and it’s still a good idea to experiment with the following exercises, but you probably don’t have to drop weight.

But if as soon as you hit 80 percent of your 1-rep max, your knee goes further inward than your toes? You should probably stop squatting that heavy until you can correct the issue.

Yelling “knees out” in your head can be surprisingly effective, but Horschig says the key to fixing knee valgus is the pistol squat.

“A lot of the time athletes won’t show that bad coordination or movement in a regular squat, but when you give them a pistol squat it comes out,” says Horschig. “That’s because they have a poor ability to coordinate hip muscles and the glute medius, the muscle on the outside of the body that controls abduction. If that muscle isn’t working correctly, it allows the body to sort of compensate and allow the knee to cave in when it’s called upon to do a very powerful movement.”

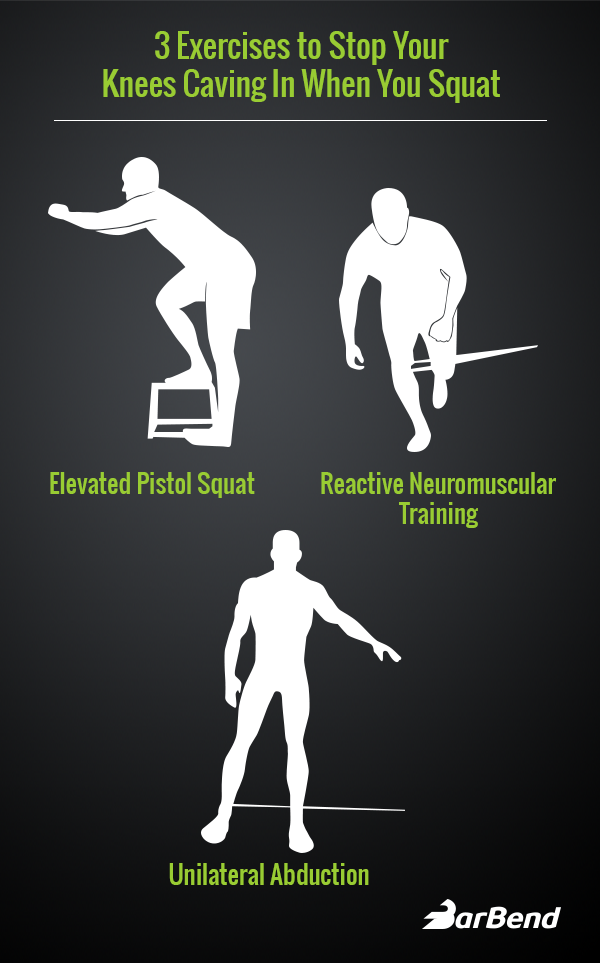

So while hip abduction exercises are handy and squatting with bands around your knees is also great, you want to find a way to work in single leg movements too, as they’re more demanding. Horschig uses the following three, often before squats begin so as to prime the body to move well during the lift.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BWidPxrj2OR

Elevated Pistol Squat

“This is a very tiny lift, standing on a box that’s two, four, maybe six inches high and you’re just doing a single-leg squat,” says Horschig. “Tap your heel and come back up. If your knee wobbles all over, that’s like an ‘Ah ha’ moment.”

Trying to hit a pistol squat without wobbling can be enough to stimulate the glutes, abductors, and other muscles to reduce knee valgus, but you can make things more advanced by doing a regular pistol squat while reaching one leg out to the side and the hands forward, like this:

https://www.instagram.com/p/BXbXKb7D1br

Or you can try the following training method.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BWLZW80DYuW/

Reactive Neuromuscular Training

This is a pistol squat with a band pulling the knee inward. The idea is to teach the body what a bad position is so it can learn to correct it — to teach it to feel for that collapse. It allows the body to turn on those glutes in the lateral side of the body and keep the knee stable and inline.

Doing exercises like this with enough repetition teaches the body to recognize and react to movements that are poor so it can stabilize the body when it trains again. It’s basically muscle memory.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BRjaV7ujWLF/

Unilteral Abduction

Finally, you can consider doing a standing unilateral abduction with a band around the ankle and a small hinge at the hip. But there’s a twist: it looks like a strength exercise for the leg that’s kicking out to the side, but it’s actually a stability exercise for the standing leg.

“As you’re kicking out to the side with the free leg, your body’s getting a stimulus that for most people would allow the knee to cave in,” says Horschig. “So if you do enough of those reps, you’ll feel the lateral glutes of your standing leg clicking on to maintain stability.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/BRdkTR2Fu6G/

Wrapping Up

We’re not about to tell very elite, top 1 percent athletes to go back to basics and squat light until they figure out how to prevent their knee valgus but for the rest of us, it’s worth working on fixing this.

Remember, the problems caused by knee collapse don’t come all at once; they accumulate over months or years of training. That can be bad, because it means people can unwittingly train through the problem until it’s too late, but think of this article as good news: you have more control over knee valgus than you think.