Pro wrestlers, your favorite masked (or caped) superhero, and your older sibling all have something in common — at a young age, they probably seemed larger than life. A big part of that kind of heroic image comes down to being in fantastic shape. Specifically, having heaps of muscle.

Hypertrophy is the process by which you grow muscle. For bodybuilders, it’s literally everything. For strength athletes, it is a tangential but welcomed benefit of dedicated physical training. And, for the average human, hypertrophy is an insurance policy that helps guarantee a long and healthy life.

No matter your motivation for gains, you need to know how hypertrophy works before you can get after it. Consider this your introduction to the machinery of muscle growth. Here’s the skinny on getting brawny.

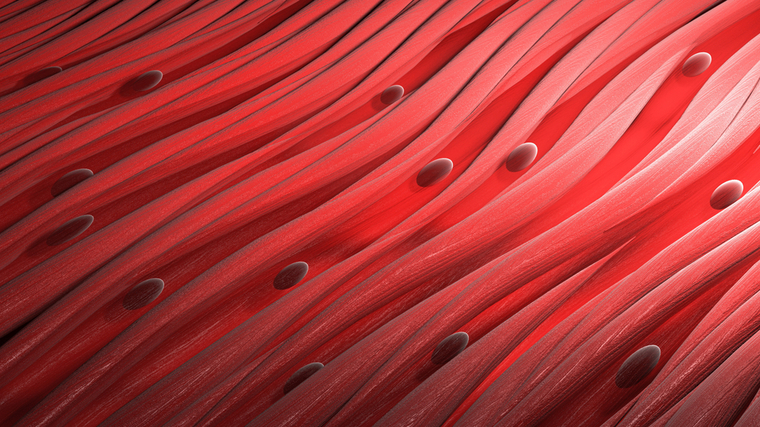

What Is Hypertrophy?

In the simplest terms, hypertrophy is synonymous with “getting bigger.” In the medical and scientific communities, hypertrophy describes the growth or enlargement of any organ or tissue.

However, in the world of fitness and physical training, hypertrophy refers to the process by which exercise creates and encourages muscle growth. (1)

If you’re a sucker for specificity, there’s another distinction worth noting — muscular hypertrophy is about enlarging your existing muscle tissue, and not necessarily creating new muscle from scratch.

The latter is called hyperplasia, which hasn’t been conclusively confirmed to occur as a result of exercise habits in human beings. (Though some researchers have managed to elicit some impressive muscle gains in cats and other animal trainees.) (2)(3)

For all intents and purposes, hypertrophy is merely what happens as a result of dedicated physical activity paired with a proper diet and the secret ingredient — time.

What Causes Hypertrophy?

The beauty of the scientific method is its consistency. When you mix the right ingredients together, you can (usually) produce a reliable result. The same holds true for muscle growth.

When your muscles are tasked with challenges they’re not used to, such as resistance training, they experience trauma. That trauma is mended in the hours and days following a bout of exercise, and in the process, your muscles rebuild stronger — and bigger — than they were before.

What constitutes muscular trauma, exactly? Most scientific literature has arrived at the conclusion that muscular hypertrophy is the result of three primary factors: (4)

- Mechanical Tension

- Muscle Damage

- Metabolic Stress

Mechanical Tension refers to the physical force of external resistance (think a barbell or even your own body weight) placed upon a given muscle.

Muscle Damage is the actual physical breakdown of muscle tissue that results from excessive tension. This often occurs in the form of microscopic tears or lesions in the fibers themselves.

Metabolic Stress can be thought of as an accumulation of biological “waste” products like lactate that build up over the course of strenuous activity, as well as the energy demands of repairing any damage.

Unfortunately, the jury is out regarding which of these factors reigns supreme. Some studies point toward muscle damage as the most important element, while others argue that there’s more going on behind the scenes. (5)(6) However, there’s one clear consensus. If you’re after muscular hypertrophy, you need both muscle protein synthesis and the right number of calories as well. (6)(7)

[Read More: Powerbuilding Workout Routine, With Tips from a CPT]

Protein Synthesis

Protein synthesis is exactly what it sounds like — it’s how your body uses protein (and other nutrients) to repair and regrow muscle tissue. This means understanding one crucial fact: in the matter of muscle growth, your exercise habits and nutritional choices are inextricably linked.

While nutrients like carbohydrates and dietary fat play a role in the big picture of hypertrophy, dietary protein and total calories are far and away the two major players on the board. (8)

Protein comes with a slew of health benefits for the average person, but your needs shoot up dramatically if you’re hitting the gym multiple times a week to pack on muscle. There are many, many papers espousing different values of “ideal” protein intake, but most modern meta-analyses land somewhere around the 1.6 to 2.2g/kg area. (8)(9)

For an easy-to-remember figure, this means that you’ll want to eat somewhere around one gram of protein per pound of body weight. You can err on the lower side if you’re in a caloric surplus, but you’ll want to go for a bit extra if you’re dieting down so your body doesn’t chew through your existing muscle mass as a fuel source.

Calories, Calories … Calories?

Even if you’re brand new to working out, it’s a bit of a no-brainer — your diet and training both matter when you’re hunting muscle gains. The question is, to what degree?

Your body needs calories to fuel the process of hypertrophy. As such, it is extremely difficult to build muscle if you’re in a significant caloric deficit. (10) You’ll need to consume more calories than you expend if you want to make noticeable gains, but an exact figure for the “ideal” caloric surplus is hard to pin down. (11)

Calorie & Macronutrient Calculator

Below, you’ll find an easy and intuitive calculator that takes much of the guesswork out of the whole process. Simply plug in the requisite information and all the math is done for you.

Calorie Calculator

Take note — the greater your caloric surplus, the more liable you are to add extra body fat. If you’re too conservative, you run the risk of not fueling your body enough to grow. Where you land on that spectrum regarding your diet is a personal choice.

Putting It All Together

If you want to see the big picture, you’ve got to fit all the pieces together. Gaining muscle may sound complicated on paper, but the reality is straightforward enough.

- Hypertrophy is the growth of muscle tissue as an adaptation to strenuous exercise.

- Exercise creates hypertrophy via mechanical tension, muscle damage, and metabolic stress.

- Tension, damage, and stress are healed (in part) via muscle protein synthesis.

- Dietary protein and calories are required to repair your muscles and elicit hypertrophy.

Benefits of Increasing Hypertrophy

Muscle gain isn’t just for the aspirant bodybuilder looking to bag their pro card or the big-timer who wants to win the Mr. Olympia competition. From athletes to the elderly, there are plenty of reasons to make muscle growth a priority in your exercise regime.

Bigger Muscles

It may be the most obvious thing in the world, but it bears repeating. If you want to bulk up, you’ve got to train for it. Mountainous biceps or chiseled quadriceps aren’t going to appear of their own accord, but you can create the physique you want if you’re diligent about your exercise habits.

More Strength and Power

Generally speaking, a bigger muscle is a stronger muscle. So, if you’re a powerlifter or Olympic lifter whose sole goal is improving your total, you probably shouldn’t neglect your pump work altogether.

In fact, science has observed some very interesting phenomena about the intersection of muscle size and strength. When studying highly-trained bodybuilders and powerlifters in a controlled setting, researchers found that the bodybuilders were actually able to produce more knee extension torque than their strength-specialist counterparts. (12)

Further, your fast-twitch muscle fibers, which are responsible for much of your overall power output, are more sensitive to high-intensity hypertrophy training. (13) Even your accessory work can help you perform better on the platform.

A Higher Metabolism

Even though adding inches to your arms won’t necessarily turn you into a calorie-burning machine, putting on lean mass absolutely affects your overall metabolism. Muscle, by nature, demands a higher influx of energy than fat, which mostly sits idle waiting to be used.

As such, if you increase the amount of muscle on your frame, you’ll boost your overall metabolic rate and potentially even dampen the metabolic slowdown that accompanies aging. (14)(15)

Injury Prevention & Management

The same methods you use to increase hypertrophy also bring happy health-related benefits as well. Resistance training not only improves muscle size and thickness, but also the capacity of your muscles to stabilize your joints.

Bigger muscles are therefore a great way to help manage injury risk both in and out of the gym. (16) Whether you’re a youth athlete or are getting on in life and worried about the odd bump or stray fall, you should be training for size on some level. (17)

How to Train for Hypertrophy

If you’ve been sufficiently sold on the promise of looking better, feeling stronger, and having a more robust and resilient body overall, all that remains is to get your hands dirty in the gym.

While strength training programs adhere strictly to spreadsheets and precise math, there’s a bit more leeway and room for creativity when you’re training for muscle gain.

As long as you’re working with decent volume, moderate rep ranges, and adhering to some form of progressive overload, you’re good to go.

Hypertrophy Sets and Reps

Despite what you may read in a muscle magazine, there’s no magic set or repetition “zone” for encouraging hypertrophy. Most contemporary research has displayed that you can make muscle gains with six-rep sets, or 12, or even 20 and above. (18)

What matters is your overall level of effort. As long as you’re taking your sets to near-failure a majority of the time, you can work with as many or as few reps as you want (within reason).

Hypertrophy Frequency and Intensity

Just like there’s no magic number of reps to make gains with, how often you work out is more of a personal preference than an absolute rule. While training a given muscle or muscle group twice per week is almost universally better than once, pushing your frequency further than that isn’t well-supported as a viable means of making gains. (19)

You should begin to notice a pattern at play here — the “ideal” amount of training isn’t an exact value, and how you choose to do enough work is (mostly) up to you. A few ultra-heavy sets are likely to do fine if you can handle them, but so will high-rep work. The most reasonable approach is to tread the middle ground.

Sample Hypertrophy Workout

This leg-focused workout should provide you with a frame of reference for how most hypertrophy-oriented sessions tend to look. While it is by no means exhaustive, you’ll notice many of the crucial elements are accounted for.

A balanced mix of compound and isolation movements, a variety of rep ranges, and the opportunity to select which movement fits your body the best are all on offer here.

- Back Squat or Front Squat: 3×6

- Romanian Deadlift or Good Morning: 3×8

- Walking Lunge or Glute Kickback: 2×12

- Leg Extension or Cyclist Squat: 3×15

How to Eat for Hypertrophy

“Eating for hypertrophy” is simply another way to say that you’re bulking up. While the hypertrophic process isn’t something you can directly control, your dietary choices will strongly influence the outcome. How much muscle you stand to gain as a result of your workouts, what percentage of your total weight gain is lean mass or fat, and how much water weight you’re holding all depend on your decisions in the kitchen.

Step 1 — Find Your Maintenance

In order to consume a caloric surplus, you need to know what your maintenance intake is — the number of calories you need to stay at your current weight, based on how much energy you spend at rest plus all of your combined physical activity.

You can figure out your maintenance calories by using a calculator, a pre-existing formula, or tracking your nutrition for a few weeks and monitoring your scale weight.

Step 2 — Choose Your Surplus

Since there’s no known “optimal” caloric surplus for muscle growth, (11) finding the right number of excess calories is both a personal choice and will likely take a bit of trial-and-error. In theory, 500 extra calories per day should net you about a pound of extra weight every week. If every ounce of it were muscle, that would be great, but it’s a bit ambitious (and unrealistic) to think so.

[Read More: How to Choose the Best Protein Powder, According to an R.D. ]

If you want to maintain your current level of body fat as much as possible, start with a conservative surplus — 200 or 300 extra calories per day. Monitor your weight and adjust as needed.

Step 3 — Adhere

Once you know your baseline and how far beyond it you’re willing to go in the pursuit of muscle gain, there’s really nothing else to do. Hit the gym, stay on top of your diet, and wait. If you’re training hard and regularly eating above your maintenance levels, you’re bound to put on mass.

Best Supplements for Hypertrophy

If you can’t get all your nutritional needs filled by whole foods, don’t fret. Supplements shouldn’t occupy the majority of your diet, but they’re great in a pinch. These are a few of the better options you can turn to if you’re looking to bulk up.

Protein Powder (Or a Mass Gainer)

Hitting your daily protein target can be a pain, especially if you’re on the larger side. When that fourth or fifth chicken breast starts to turn your stomach, a good protein powder can save the day. Gram for gram, protein powders provide more of a direct nutritional stimulus without the hassle of cooking (or chewing).

If you’re struggling to get enough calories in, mass gainers — protein supplements that are intentionally laden with exorbitant numbers of calories — can also help to fill the gaps in your nutrition.

Creatine

Few supplements on the market do as much as creatine. For how many benefits it provides you both in and out of the gym, creatine monohydrate is an absolute steal.

Five grams per day mixed into your morning oatmeal, your post-workout shake, or stirred up in a glass of water is all you need. Fire and forget.

Pre-Workout

If your workouts don’t meet a certain level of intensity, you’re not likely to grow from them. Adaptation simply doesn’t occur without challenge and, if you’re sluggish or tired in the gym, it can be difficult to challenge yourself. A solid pre-workout can amp you up before you set foot in the gym doors and get you in the right state of mind for the day’s training.

Mass Is in Session

Training for muscular hypertrophy doesn’t mean you’re obligated to start meal prepping in anticipation of an upcoming physique show (though a tighter dietary plan will certainly help most of the time). Moreover, you won’t ever accidentally put on too much muscle, no matter how hard you try.

What will happen, though, is worth every set and rep you squeeze out in the gym. Bigger muscles, stronger joints and ligaments, more confidence (both in and out of the weight room), and a whole lot more. If you want to win that hyper trophy, all you’ve got to do is grab your gym bag and get after it.

References

1. Damas, F., Phillips, S. M., Libardi, C. A., Vechin, F. C., Lixandrão, M. E., Jannig, P. R., Costa, L. A., Bacurau, A. V., Snijders, T., Parise, G., Tricoli, V., Roschel, H., & Ugrinowitsch, C. (2016). Resistance training-induced changes in integrated myofibrillar protein synthesis are related to hypertrophy only after attenuation of muscle damage. The Journal of physiology, 594(18), 5209–5222.

2. Taylor, N. A., & Wilkinson, J. G. (1986). Exercise-induced skeletal muscle growth. Hypertrophy or hyperplasia?. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 3(3), 190–200.

3. Giddings, C. J., & Gonyea, W. J. (1992). Morphological observations supporting muscle fiber hyperplasia following weight-lifting exercise in cats. The Anatomical record, 233(2), 178–195.

4. Schoenfeld B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 24(10), 2857–2872.

5. Damas, F., Libardi, C. A., & Ugrinowitsch, C. (2018). The development of skeletal muscle hypertrophy through resistance training: the role of muscle damage and muscle protein synthesis. European journal of applied physiology, 118(3), 485–500.

6. Damas, F., Phillips, S. M., Libardi, C. A., Vechin, F. C., Lixandrão, M. E., Jannig, P. R., Costa, L. A., Bacurau, A. V., Snijders, T., Parise, G., Tricoli, V., Roschel, H., & Ugrinowitsch, C. (2016). Resistance training-induced changes in integrated myofibrillar protein synthesis are related to hypertrophy only after attenuation of muscle damage. The Journal of physiology, 594(18), 5209–5222.

7. Wackerhage, H., Schoenfeld, B. J., Hamilton, D. L., Lehti, M., & Hulmi, J. J. (2019). Stimuli and sensors that initiate skeletal muscle hypertrophy following resistance exercise. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 126(1), 30–43.

8. Morton, R. W., Murphy, K. T., McKellar, S. R., Schoenfeld, B. J., Henselmans, M., Helms, E., Aragon, A. A., Devries, M. C., Banfield, L., Krieger, J. W., & Phillips, S. M. (2018). A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training-induced gains in muscle mass and strength in healthy adults. British journal of sports medicine, 52(6), 376–384.

9. Phillips, S. M., Chevalier, S., & Leidy, H. J. (2016). Protein “requirements” beyond the RDA: implications for optimizing health. Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism = Physiologie appliquee, nutrition et metabolisme, 41(5), 565–572.

10. Murphy, C., & Koehler, K. (2022). Energy deficiency impairs resistance training gains in lean mass but not strength: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 32(1), 125–137.

11. Slater, G. J., Dieter, B. P., Marsh, D. J., Helms, E. R., Shaw, G., & Iraki, J. (2019). Is an Energy Surplus Required to Maximize Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy Associated With Resistance Training. Frontiers in nutrition, 6, 131.

12. Tesch, P. A., & Larsson, L. (1982). Muscle hypertrophy in bodybuilders. European journal of applied physiology and occupational physiology, 49(3), 301–306.

13. Tesch P. A. (1988). Skeletal muscle adaptations consequent to long-term heavy resistance exercise. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 20(5 Suppl), S132–S134.

14. Zurlo, F., Larson, K., Bogardus, C., & Ravussin, E. (1990). Skeletal muscle metabolism is a major determinant of resting energy expenditure. The Journal of clinical investigation, 86(5), 1423–1427.

15. Roubenoff R. (2003). Sarcopenia: effects on body composition and function. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences, 58(11), 1012–1017.

16. Fleck, S. J., & Falkel, J. E. (1986). Value of resistance training for the reduction of sports injuries. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 3(1), 61–68.

17. Walters, B. K., Read, C. R., & Estes, A. R. (2018). The effects of resistance training, overtraining, and early specialization on youth athlete injury and development. The Journal of sports medicine and physical fitness, 58(9), 1339–1348.

18. Krzysztofik, M., Wilk, M., Wojdała, G., & Gołaś, A. (2019). Maximizing Muscle Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review of Advanced Resistance Training Techniques and Methods. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(24), 4897.

19. Schoenfeld, B. J., Ogborn, D., & Krieger, J. W. (2016). Effects of Resistance Training Frequency on Measures of Muscle Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 46(11), 1689–1697.

Featured Image: Prstock-studio / Shutterstock