A balanced diet and resistance training are essential for maintaining overall health. They provide nutrients needed for bodily functions while enhancing strength for everyday activities. One benefit is their role in supporting bone health.

Jonathan Bennion, a physician assistant, anatomist, and director at the Institute of Human Anatomy, recently explored the intricate connection between diet, exercise, and bone health. Through a detailed dissection of bone anatomy, Bennion revealed how proper nutrition and regular physical activity are crucial for keeping bones strong and healthy.

Your bones are constantly building up new bone tissue and also breaking down old bone tissue.

—Jonathan Bennion

Bone tissue is a living, dynamic structure that is constantly evolving and undergoing remodeling.

[Related: What Should You Drink to Stay Legit Hydrated]

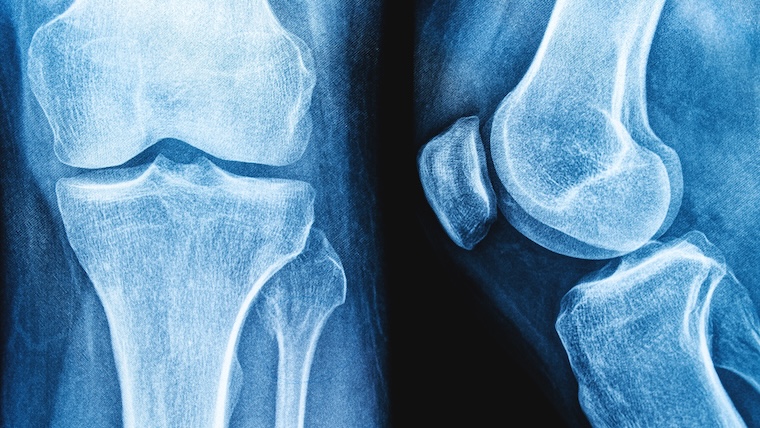

Compact Bone

Bennion explained that the outer layer of bone, known as the “compact bone,” is a dense exterior found in all bones. Despite its density, it can be relatively thin at the ends of bones and is not entirely solid.

On a microscopic level, compact bone reveals a surprisingly porous structure. It features a complex network of interconnected canals that house blood vessels and repeating circular units called osteons. These osteons are aligned parallel to the length of the bone, providing significant strength and durability.

Examining an osteon reveals concentric rings of solid, hard bone tissue. Within these rings lie embedded cells called osteocytes, responsible for maintaining bone health by exchanging nutrients and waste products with the blood. Since osteocytes are encased within rigid bone tissue, how do they distribute nutrients and remove waste?

Bennion explained that at the center of each osteon lies a central canal containing blood vessels. Before the bone hardens and traps the osteocytes in place, these cells extend cytoplasmic projections — tiny “arms” that connect with neighboring osteocytes in the same ring and adjacent rings. This intricate cellular network forms a pathway to transport nutrients efficiently, waste, and other essentials.

Extracellular Matrix

Bennion referred to the dense bone tissue forming the circular plates of bone as the extracellular matrix. This matrix gives bone unique properties, combining strength with a touch of flexibility.

Collagen and Hydroxyapatite

A closer look at the extracellular matrix reveals that bone comprises collagen and hydroxyapatite, a remarkable, crystal-like substance. This mineral gives bone unique properties and exceptional strength, enabling it to withstand compression and crushing.

Hydroxyapatite is formed from calcium phosphate and hydroxide, making calcium essential for bone health. Its critical role lies in producing hydroxyapatite, which ensures the resilience and durability of our bones.

Vitamin D is needed to absorb calcium.

—Jonathan Bennion

Bennion highlights that collagen isn’t just beneficial for the skin; it’s also the most abundant protein in the human body and plays a crucial role in bone structure. (1) This protein fiber provides remarkable tensile strength, helping bones resist being pulled apart. Healthy bones are composed of approximately 30% collagen and 55% hydroxyapatite, a mineral that reinforces bone hardness.

Maintaining the right balance between collagen and hydroxyapatite is essential, as any imbalance can lead to specific bone-related conditions. For instance, rickets and osteomalacia (soft bones) arise from a vitamin D deficiency, which hinders calcium absorption.

This results in excess collagen relative to hydroxyapatite, causing bones to become smoother, bent, or deformed. Conversely, osteogenesis imperfecta occurs when the body fails to properly synthesize collagen, leading to brittle, fragile bones prone to fractures.

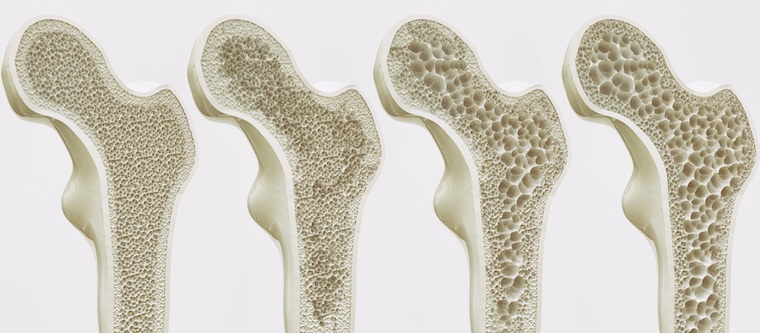

Spongy Bone

Beneath the compact bone lies spongy bone, an intricate and highly organized structure of tiny, beam-like formations called trabeculae. These trabeculae create small interconnected spaces where blood vessels weave in and out, bringing nutrients close to the bone cells that form the beams.

Nestled within these spaces is red bone marrow, a vital tissue responsible for producing red blood cells (erythrocytes), white blood cells (lymphocytes), and platelets (thrombocytes). Blood vessels passing through the red bone marrow collect these newly formed blood cells and distribute them throughout the body.

In adults, red bone marrow is primarily found in the axial skeleton, including the skull, spine, sternum, rib cage, and pelvis, as well as in the proximal ends of the humerus and femur.

Though the arrangement of spongy bone may appear random at first glance, it’s meticulously aligned to withstand the specific stress forces the bone experiences, showcasing its remarkable design and functionality. “Essentially, we have this marvelous biological architecture designed inside our bones. It’s incredible,” Bennion stated.

Exercise and Bone Health

Bennion explained the roles of two key cells in bone health: osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Osteoclasts break down and reabsorb old bone tissue, while osteoblasts create new bone tissue by depositing extracellular matrix. Over time, this matrix calcifies, trapping the osteoblasts and transforming them into osteocytes.

When osteoblast activity matches that of osteoclasts, bone density remains stable. However, as we age, bone density naturally declines. Engaging in exercises, particularly resistance training, can stimulate osteoblasts to work more actively than osteoclasts, leading to increased bone density and stronger bones.

This is one of the reasons why exercise is great for long-term bone health, especially when we start to hit our 30s.

—Jonathan Bennion

Bone density peaks in one’s 30s and declines thereafter. However, this process can be slowed through impact activities and resistance training, alongside maintaining a diet rich in calcium and vitamin D. (2)

Unfortunately, women are about eight times more likely than men to develop osteoporosis, a condition characterized by a significant loss in bone density, particularly after menopause.

This increased risk is due to estrogen’s role in protecting bones by inhibiting osteoclasts — cells responsible for breaking down bone tissue. When estrogen levels drop during menopause, osteoclast activity increases, leading to greater bone resorption and reduced density, especially in spongy bone. Engaging in regular exercise can help mitigate this progression. (3)

Although osteoporosis is less common in men, it can still occur. Testosterone, like estrogen, protects bone health, but its levels gradually decline with age, increasing the risk over time.

Wrap Up

Resistance training and proper nutrition become essential for maintaining healthy bones as we age. A well-rounded diet should include calcium, vitamin D, vitamin K, magnesium, omega-3 fatty acids, and key macronutrients to support bone strength. Regular exercise helps slow the loss of bone density and reduces the risk of developing common bone-related conditions later in life.

More In Research

- Fructose: Friend or Foe?

- Creatine Monohydrate vs. Hydrochloride — What’s the Difference?

- Develop These 5 Habits for a Leaner Physique

References

- Wu M, Cronin K, Crane JS. Biochemistry, Collagen Synthesis. [Updated 2023 Sep 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507709/

- Dawson-Hughes, B., Harris, S. S., Krall, E. A., & Dallal, G. E. (1997). Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone density in men and women 65 years of age or older. The New England journal of medicine, 337(10), 670–676. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199709043371003

- Nguyen, T. V., Sambrook, P. N., & Eisman, J. A. (1998). Bone loss, physical activity, and weight change in elderly women: the Dubbo Osteoporosis Epidemiology Study. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research, 13(9), 1458–1467. https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.9.1458

Featured image via Shutterstock/SofikoS