Sometimes, the weirdest-looking exercises can be the most useful, and the Jefferson deadlift is the perfect example.

It’s weird. There’s about a one hundred percent chance you’ll attract looks in the gym. But it has some pretty extraordinary benefits.

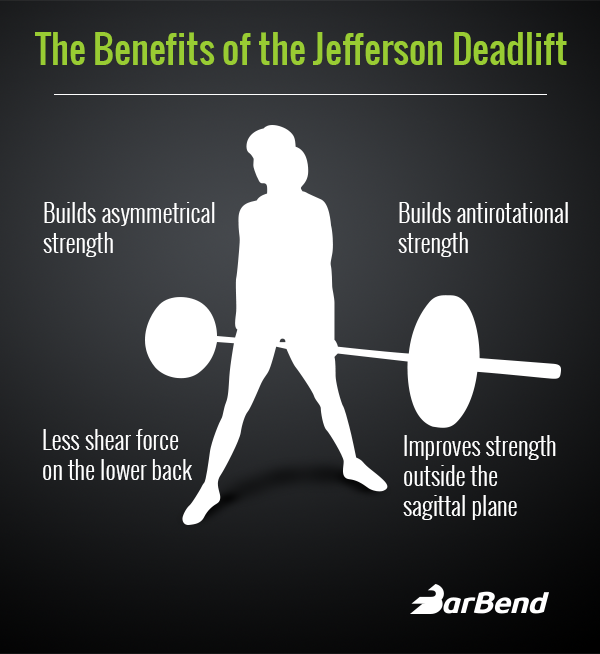

Thanks to Jen Sinkler for appearing in this graphic.

Why

“The cool thing about it is it gives you a lot of things that other big, heavy, typical compound lifts don’t do,” says Dave Dellanave, a Minneapolis-based strength coach who broke the world record in the Jefferson deadlift when he pulled 605lb at 200lb bodyweight.

It combines asymmetry, rotation, hip hinging, and heavy loading all at once. Dellanave points out that the lift is similar to a trap bar deadlift, so there’s much less shear force on the spine, but it involves rotation, so it’s a multiplanar exercise that builds asymmetrical and anti-rotational strength. Because the feet are staggered, your torso will want to turn to face the same direction as the feet, and to keep your chest facing forward, you’ll need to engage your deep core stabilizers.

While a lot of us know that we should incorporate multiplanar movements to reduce injury and improve overall strength, we often approach anti-rotational, asymmetrically-loaded exercises the wrong way.

“The fact that you can load it heavy is really important,” Dellanave says. “Most people do heavy deadlifts and then they do light, single-leg kettlebell deadlifts and think they balance each other out. The body doesn’t work that way. So, the fact that you can load it heavy is the big benefit.”

If your conventional deadlift numbers are stalling or they’re causing back pain, spending a few weeks subbing with Jefferson deadlifts may be an effective way to break through a plateau or reduce or eliminate pain. Here’s how to do it.

How to Do It

Straddle the bar with your feet shoulder width or a little wider, grab it beneath your shoulders, and stand up. Make sure the weight is centered between both feet, and take care your knees don’t cave inward when you start pulling.

You can experiment with different grips, but try to stay relatively balanced by alternating your front and back foot for equal amounts of time. (Dellanave simply alternates his sets.) An exception to this rule is if you have a serious asymmetry, like scoliosis, in which case it’s best to train the side that feels more comfortable, once your doctor gives the go ahead.

As is the case with the trap bar deadlift, the Jefferson should be closer to a squat than a hinge. (In fact, it’s sometimes called the Jefferson squat.) If you’re leaning forward a lot in a hinge motion, it’s possible you won’t have good leverage.

Dellanave emphasizes that the leverages are different for everyone based on their anthropometry – some people wind up with something that looks almost exactly like a trap bar deadlift with just a little twist, but some don’t have the leverage for it and it winds up much more rotational. That’s lifting, after all: no two lifters move exactly alike. But the good thing about the lift is that it tends to be self-correcting – there’s no single best way to do it, so the lifter is free to find the leverage that works best for them.

“One of the things I like is that because it’s so odd, people tend to feel OK playing around with it and finding the strongest position for them,” he says. “People are always jamming a round peg into a square hole with the traditional lifts, because they think there are so many lifts that need to be an exact way. The Jefferson deadlift helps you play around a little more to find what’s best for you.”

Common Sticking Points

The most common form mistake is letting the heel of the back foot lift up. That means the lifter isn’t firmly grounded with both feet and he or she is putting more weight on one leg than the other.

Despite its awkward and off-balance appearance, the Jefferson should load both legs pretty symmetrically. If it isn’t, the lifter is probably setting up with their foot too far behind them. Moving the feet more in line with each other while keeping them roughly shoulder width or a little wider will get the job done better.

When to Do It

As we mentioned above, it’s a great way to train the legs and back with less shear force on the spine, and Dellanave has found that for many of his clients with back pain, concentrating on the Jefferson for a few weeks can help them return to conventional deadlifts pain free.

It’s also great for busting through strength plateaus.

“For my powerlifters, when they’re in their off season or they don’t have a meet for a couple of months, I’ll have them trade out their normal deadlift stance for a Jefferson and train with low reps,” says Dellanave. “We’ll do that for like, four weeks. If they’ve stalled in their deadlift progress, getting them stronger in a different stance and bumping up their best sumo and best Jefferson inevitably breaks through their plateau in the conventional deadlift.”

Finally, if nothing else, it’s a dynamite accessory movement for developing the quads, which is one of the reasons bodybuilder Kai Greene is such a fan of the exercise.

Wrapping Up

In short, its strength is its weirdness. It’s one of the few asymmetrical and anti-rotational movements that allow serious weight to be lifted, it fits neatly into powerlifting and strength training plans, it’s easy on the back, and it allows for some variety in the old squat, dead, bench rotation.

When you’re straddling the bar, enjoy the looks. Given all of the benefits of the Jefferson deadlift, you can be weird with pride.

Featured image via @yanikokozaki on Instagram.