If someone strolls up to you in the middle of the gym and abruptly commands you to flex, chances are that you’re going to ball up your fists, raise your arms, and bang out the classic front double biceps pose. It’s a posture so synonymous with bodybuilding that it has been the de facto means of displaying muscularity since the heyday of Charles Atlas.

Along with knowing how to flex your biceps comes an understanding that you need something to flex in the first place. Whether you dangle plates from your waist to perform weighted pull-ups or do curl after curl (after curl), you probably pursue bigger arms in some fashion.

But that does beg the question; what exactly counts as “big arms”? More specifically, what’s the average biceps size? To find out, you need to know where you fall on the scale of ordinary and supernatural.

What Is the Average Biceps Size?

For an entire generation of children, professional wrestler Hulk Hogan introduced the concept of prodigious arms — “The 24-inch pythons, brother!” — and the giant-slaying strength that accompanied them. If you fell into that camp, whipping out the tape measure might’ve proved disappointing.

Little did you know, though, that the average bloke isn’t boasting 24-inch arms; far from it. In fact, if you want to compare your biceps to the general populace (rather than one of the most iconic stars of pro wrestling), you’ll probably come out pretty favorably.

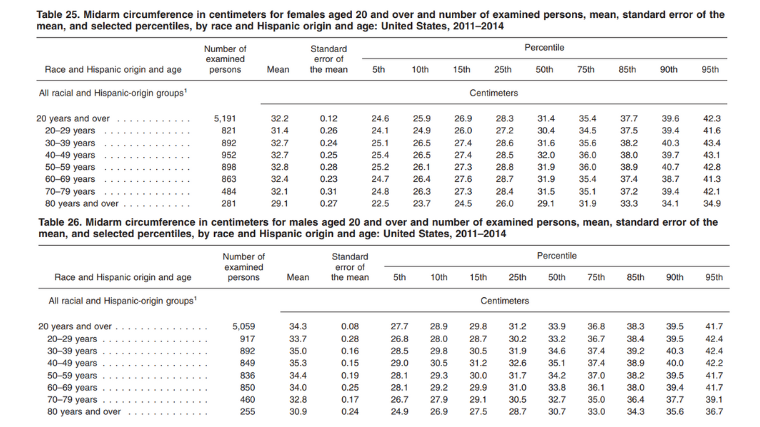

Credit: National Center for Health Statistics, Vital Health Stat 3

[Read More: The Best Biceps Stretches to Support Long-Term Arm Thickness]

For example, by evaluating the study results provided by the Centers for Disease Control, (1) you can see where the averages and extremes of the biceps size distribution scale reside for individuals of both sexes.

- Amongst females, those in the 50-to-59-year-old age group possess the largest mean arm circumference at 32.8 centimeters (12.91 inches), while females of the 40-to-49-year-old category have the widest arms at the 50th percentile at 32.0 centimeters (12.59 inches).

- When measuring males, the 40-to-49-year-old age group possessed the meatiest average mean arm circumference at 35.3 centimeters (13.90 inches), and also the thickest arms at the 50th percentile range at 35.1 centimeters (13.81 inches).

- The largest recorded averages for all males on the chart — those in the 95th percentile — belong to males in both the 20-to-29-year-old and 30-to-39-year-old age groups. Both cross sections have average midarm measurements of 42.4 centimeters (16.61 inches).

- The highest 95th-percentile averages belong to females in the 30-to-39-year-old age division who collectively possess a 95th-percentile average midarm circumference of 43.4 centimeters (17.08 inches).

Considerations

There are two important factors to consider when looking at this data. The first is body composition; the CDC doesn’t remark on muscle-to-fat ratios, so there’s no way of knowing if these arm measurements were taken on individuals who regularly hit the weights or not.

Secondly, measuring the circumference of the upper arm doesn’t isolate the size of the biceps specifically, since you’re counting the surface area of the triceps as well. In fact, the triceps are proportionally larger than the biceps by default, with the volume ratio landing at about 3:2 in favor of the tris. (2)

Measuring the circumference of the arm is the most objective way of calibrating biceps size, sure. But that also means if you want “bigger biceps” — on paper, at least — you should hammer your triceps as well.

Defining “Big Biceps”

The public perception of what big biceps are (and how easy it is to grow them) has been skewed by the massive appendages of those whose arms fall squarely outside the realm of “normal.” Rest assured that, no matter how hard you train, you won’t accidentally put on too much muscle and wake up with biceps that would win the crowd at a bodybuilding show.

Professional Bodybuilder Biceps Sizes

In the world of professional bodybuilding, size is everything. While you can’t hide from the fact that many pro physique athletes turn to performance-enhancing drugs to augment their gains, 20-inch-plus arms aren’t the exception; they’re the rule.

Consider the arm sizes of some iconic winners of the International Federation of Bodybuilding & Fitness (IFBB) Mr. Olympia competition, the sport’s most prestigious event:

- Sergio Oliva: 20.5 inches

- Arnold Schwarzenegger: 22 inches

- Ronnie Coleman: 22 inches

- Phil Heath: 23 inches

- Mamdouh “Big Ramy” Elssbiay: 24 inches

Editor’s Note: These figures aren’t 100-percent substantiated. Reports on the arm size of specific competitors may vary.

And those are just a few of the Sandow trophy winners; non-winners with some seriously impressive guns include the likes of Flex Wheeler and Roelly Winklaar, who both boasted 24-inch arms.

Outside of Bodybuilding

20-inch (or larger) biceps may be uncommon outside of the bodybuilding stage, but they’re not unheard of — especially in strength sports where the mightiest mortals tend to congregate.

For example, two of the girthiest arms ever publicly measured belonged to strongman Manfred Hoeberl, a six-foot, four-inch colossus whose barbell-based achievements include a 628-pound bench press and 794-pound squat. After a curling competition at the 1994 Arnold Classic in Columbus, Ohio, Hoeberl’s biceps were measured at an astounding 26 inches.

[Read More: The Best Biceps Exercises to Use for Mass and Strength]

Pro wrestler turned Hollywood superstar Dwayne “the Rock” Johnson also reportedly carries 21-inch arms around on the set of his action blockbusters. Despite pursuing a career in film full-time, Johnson isn’t shy about showing off his gut-busting workouts on social media, either.

Compared to the CDC’s data, these measurements certainly sound extreme — and that’s because they are. That said, just because you don’t measure up to a five-time Olympia winner doesn’t mean your own biceps are diminutive. If you hit the gym for muscle hypertrophy on a regular basis, you’ve probably got biceps that are safely above average.

How to Grow Your Biceps

If you want to build your biceps, you need to know how they work in the first place. Your biceps brachii articulate (that is, insert upon) your elbow joint. Your elbow joint essentially functions like a hinge that opens and closes.

For training purposes, this means that any amount of weight you apply to your arm as your biceps attempt to “close” your elbow joint will stimulate them in some way. This predictable and uncomplicated movement pattern makes your biceps easy to overload with resistance training and, in the process, induce the tremendous size gains you’re looking for.

[Related: Bodybuilding Lore Addressed: Can You Really Build a Biceps Peak?]

Most direct biceps training is as simple as performing your curl variations of choice. On the other hand, many upper body pulling exercises such as rows or chin-ups work your biceps as well (albeit not as directly). Generally speaking, most good biceps-building workout plans will include both compound exercises and isolation lifts for the arms.

The Three Best Biceps Exercises

If your desire is to induce explosive bicep growth as quickly as possible, here are three exercises that you’ll want to add to your exercise routine immediately (if you’re not doing them already.)

Chin-Up

The chin-up is a compound exercise that also involves a substantial contribution from the muscles in your back. With that being said, the chin-up remains one of the safest and most reliable ways to overload your biceps while training them in concert with your other muscles that are responsible for pulling.

When you do chin-ups, you’re instantly recruiting your biceps to move a portion of your own body weight, but if you ever find yourself getting so strong that sets of 12 chin-ups don’t even come close to tiring you out, you can always suspend additional weight from a belt, or hold a weight between your legs, in order to rapidly escalate the challenge.

How to Do the Chin-Up

- Hang from a pull-up bar with your palms facing you, and your hands about shoulder-width apart or slightly wider.

- Squeeze your shoulder blades together from a dead hang and pull them down away from your ears to initiate the movement.

- Pull your body up until your chin is at or above the bar, making sure not to let your body fold inward.

- Hold for a moment at the top, contracting your biceps and back as hard as possible, and then reverse the motion.

Coach’s Tip: Wrapping your thumbs around the bar you’re hanging from may help you engage your biceps a bit more.

Sets and Reps: Perform multiple sets of chin-ups, leaving several repetitions in the tank, until you can do 20 to 30 in a single session. Then, drop the reps and add a small amount of weight.

Barbell Curl

The barbell curl sits comfortably at the top of the list of classic biceps-builders, and for good reason. Standing upright allows you to brace your entire body for stability. You can even rest your back against a wall to isolate your biceps and make light weights feel heavy. Or, deliberately sway back and forth and perform a cheat curl for some insane tension.

Whether you’re using a straight bar, an EZ-curl bar, or any of the myriad other specialty bars in existence, standing barbell curls are one of the go-to exercises for isolating your biceps. This enables you to fully focus on the contribution of the biceps to the lift and ensure their full engagement throughout the movement.

How to Do the Barbell Curl

- Grab a barbell with an underhand grip, slightly wider than the shoulders.

- Pull your shoulders back. Your elbows should be under your shoulder joints, or slightly in front.

- Curl the barbell up using your biceps.

- Hold the barbell for a second at the peak of the movement before returning it to its starting position.

Dumbbell Curl

By swapping out the barbell for a pair of dumbbells, you can retain nearly all of the benefits of the standing barbell curl while also adding to the versatility of the curling motion. Dumbbells permit you to work your biceps uniquely as you rotate your palms outward while you raise the weight. They also allow you to quickly identify weaknesses specific to each arm.

In addition, the fact that you can alternate your arms and lift the dumbbells individually may result in you being able to lift more weight per arm than you could lift with a barbell. In other words, even though each of your individual arms is holding a greater amount of weight, your core is still required to support less weight overall during each rep than it would when you execute a two-arm barbell curl.

How to Do the Dumbbell Curl

- Grab a dumbbell with each hand, stand upright, and hold the dumbbells at your sides with your palms facing your midline.

- Curl the weight up, rotating your hand so that your thumb points out and away from your body at the peak of the movement.

- Hold at the top of the movement for about a second, then slowly lower the dumbbells back to your sides.

Size Matters, or Does It?

There’s no getting around it: Big, bulging biceps are a status symbol. However, your biceps are but one cog in a much larger muscular machine. Pursuing big biceps is noble, but remember that you have many other muscles in your body. Skipping back or leg day for yet another round of curls may do more harm than good, especially from a performance standpoint.

If you want big biceps, you need strong shoulders to stabilize your arm while you curl or row. Likewise, your shoulders have difficulty growing if they aren’t working in the service of strong chest and back muscles. So, as you fine-tune your biceps workouts, don’t neglect to train all of the adjacent muscle groups as well.

That way, when you proudly flex your biceps and display your freshly sprouted peaks, they’ll look right at home amongst the other scenic features of an already muscular landscape.

References

- Fryar, C.D., Gu, Q., Ogden, C.L., Flegal, K.M. (2016). Anthropometric reference data for children and adults: United States, 2011–2014. National Center for Health Statistics, Vital Health Stat 3(39).

- Holzbaur, K. R., Murray, W. M., Gold, G. E., & Delp, S. L. (2007). Upper limb muscle volumes in adult subjects. Journal of biomechanics, 40(4), 742–749.