At the 2016 Summer Olympics, eight categories for Olympic Weightlifting existed for men and seven for women. In both cases the categories boasted roughly a dozen competitors or more. For those with a strict interest in weightlifting, it was clear that the sport had never been in better health. Three years later in 2019, with Tokyo 2020 fast approaching, the statement holds true. Unlike powerlifting, whose official competitions emerged in the 1960s, and the World’s Strongest Man, which first came to TV screens in 1977, the history of weightlifting extends well over a century. Bodybuilding dates to 1899 but official or modern weightlifting contests are even older.(1)

The first weightlifting contest, using standardised weights, barbells and competitive scoring, was held in 1891. Comprised of seven lifters from around the world, the event, only recognized by the International Weightlifting Federation in 1989, was a seminal moment in the history of weightlifting and strength sports more generally. It marked a shift from the circus strongman to the Olympic champion. 1896 saw weightlifting emerge at the Olympics but its origins lay in an audacious effort to entertain and inspire English audiences five years previously. Focused on the first recognized weightlifting contest of its kind, today’s post examines the motives behind the 1891 contest.

https://www.instagram.com/p/xlEMW-Nnuj/

Why Hold a Weightlifting Competition?

From the mid-nineteenth-century strongmen, and to a lesser extent, strongwomen had begun to compete against one another in feats of strength. One early example of this was George Windship, the Harvard trained physician of the 1850s, who prompted the ‘Health Lift’ previously discussed on Barbend. As part of his promotional campaign, Windship engaged in a series of strength contests with those who doubted either Windship’s strength or the benefits of his beloved Health Lift. These contests, as retold by Jan Todd, were not done in private but rather in public theaters to sold out houses. A very real, and very profitable, interest in strength competitions had emerged.(2)

[See strength historian Jan Todd discuss Scottish stone lifting in the Rogue documentary, Stoneland.]

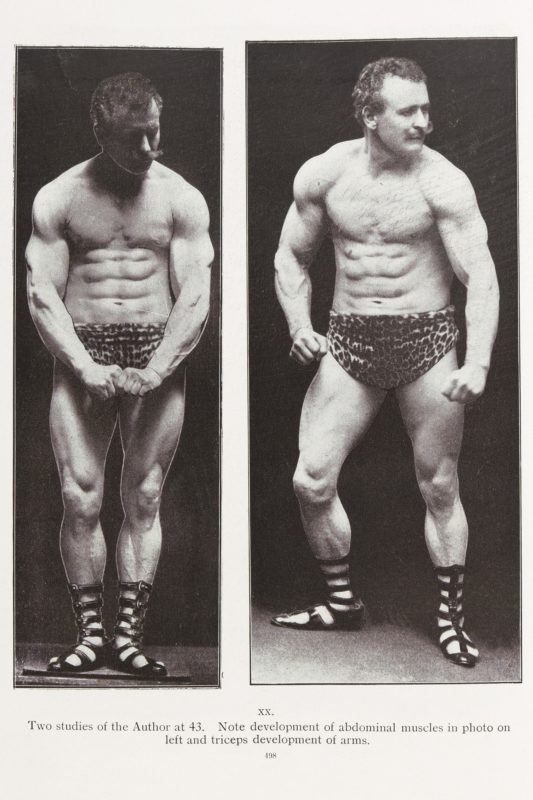

Fast forwarding to the late 1880s, the dawn of the physical culture movement, bodybuilding pioneer Eugen Sandow and his mentor Professor Attila helped amplify the public’s interest in strength. Prior to this time, weightlifting associations and competitions as we would understand them had begun to emerge in mainland Europe. In Great Britain a similar practice existed, albeit with one significant difference. Weightlifting contests, where they appeared in England, tended to be part of vaudeville performances. In their strongman shows, performers would routinely challenge members of the audience to best them in a feat of strength. It was here that Eugen Sandow, once termed the ‘World’s most perfectly developed specimen’, came to prominence.

Sandow’s first appearance in England came directly in relation to one of these challenges. In 1889, Sandow was alerted to a £500 prize offered to anyone who could defeat Charles ‘Samson’ Sampson and his sidekick Frank ‘Cyclops’ Bienkowski. Then enjoying a prolonged spell at the Royal Aquarium in London, Sampson was shocked to find that Sandow, a man who looked mortal in his evening attire, was possessed with an enviable strength. Over the course of two weightlifting contests, in which Sampson allegedly tried to cheat at several points, Sandow was declared the winner. This victory, wonderfully retold in David Chapman’s biography of Sandow, had captured the British imagination.(3) Likewise the repeated claims that both Sandow and Sampson had attempted to use fraudulent weights or devices during the contest sparked an interest in standardising weights.

Read more in our history of Eugen Sandow.

From his victory in 1889, Sandow’s celebrity continued to rise, while the general public began to take a much greater interest in exercise and a series of previously unknown strongmen stepped into the spotlight. Sandow and other strength athletes began to compete against one another in weightlifting events for the public’s amusement.(4) It was fun, it was entertaining but it wasn’t quite right.

First there was little to no standardisation in these contests. So one week Sandow or Apollo or whatever other strongman was enjoying the public’s attention, might compete in a bent-press contest but the next, it would be a two-handed press. In other instances, strongmen used dumbbells, sacks of flour or wheelbarrows for props.(5) It was, for want of a better term, a mess.

Further complicating things were allegations of foul play. Strongmen had, for centuries, been guilty of using lightweight props or advantageous set-ups during their shows. The first contests to emerge in Britain following Sandow’s victory over Sampson were no different as several strongmen were exposed for using ill balanced equipment to throw off competitors or claiming feats which far exceeded their capabilities.(6) For weightlifting to thrive as a respectable sport, it needed a recognizable standard and verifiable weights.

[Read more from the author: The Untold History of the First Bodybuilding Competition!]

Laying the Foundations

In one of the few historical studies of the 1891 contest, Gherardo Bonini traced the emergence of domestic weightlifting contests in mainland Europe to the late 1870s and 1880s.(7) While this allowed lifters in Austria, Germany or France to test their mettle, it too proved prohibitive. At a time when strongmen such as Louis Cyr and Eugen Sandow were issuing international challenges to one another, the time seemed ripe for an international contest. As London was, even by the early 1890s, the hotbed of weightlifting activity for Europeans, it should come as little surprise to learn that efforts to create an international competition began in England.(8)

This was not without its problems. First, and perhaps most pressing of all, was the fact that weightlifting contests in England in the late 1880s and early 1890s were often ill managed and ill thought out affairs. A new sponsor and a new promoter was needed, one with a true interest in the sport of weightlifting. Enter John Astley Cooper. Described by J. R. Lowerson as a ‘propagandist for athleticism’, Astley’s time in the British limelight was at its peak from the late 1880s to the mid-1890s.(9) The reason for this was simple.

At a time of increasing global uncertainty, Astley was one of the loudest and most convincing proponents for international sport as a means of peacekeeping. Competitive sport, especially between British and European athletes, would not only improve Britain’s health, but also her international relations. Prior to his interest in weightlifting, Astley financed a range of other sports including pedestrianism for this very reason. Despite his previous interests, weightlifting captivated the rich backer who linked physical strength and national strength. Who knew weightlifting could be so beneficial?

Motivated by the twin desires of finding the strongest lifter alive and promoting international cooperation, Astley helped stage a series of weightlifting contests in Britain to determine the best British weightlifter. January 24 1891 thus saw twelve English lifters face off in a series of dumbbell and barbell feats. Of the eight exercises, seven were based on dumbbell lifts, primarily using one hand. But, and this is important, a barbell exercise was included.(10)

The scene was being set for the first standardised weightlifting contest. Physical culture aficionados will be interested to learn that E. Lawrence Levy, a Birmingham based lifter who was hugely influential in promoting the sport in England, came away with the top prize. Other lifers included a young Launceston Elliot, who went on to win a gold medal in weightlifting at the 1896 Olympic Games in Athens.(11)

With his English champion determined, Astley helped organise a series of follow up events over the course of the next month.(12) This time was crucial in helping to raise awareness of weightlifting events, standardise a set of practices and help lifters come to terms with competition settings. As the contests’ structures became clearer and more efficient, Astley made his grand announcement. March 28 and 30 1891 would see the first ever international weightlifting competition.

Launceston Elliot in the 1890s

The 1891 Contest

The 28 March contest is not particularly significant, save for real anoraks of the sport. The event, which welcomed several European and British lifters, focused on eight lifts, varied between single and double handed movements with no distinctions made for weight classes or categories. It was, for want of a better phrase, more of the same as far as weightlifting was concerned but kudos must still be given to E. Lawrence Levy who won the event by a very large margin.(13)

Now, where real innovation emerged was two days later during the barbell contest. It was for this reason that Bonini described the event in such hallowed terms: ‘the true scientific speciality of weightlifting had to be performed with a barbell’. Those who chose to compete in the barbell contest were: Zafarana, Pfaun, Frangois, Wehlau, Brunhuber, Szalay, brothers Algernon and Rowland Spencer, and Launceston Elliot. It was a beautiful mix of English, Belgian, French, Polish and Italian lifters.(14)

Now somewhat frustratingly for historians, the event itself was only reported on by a handful of newspapers. Of this small bunch, the clearest descriptions were found in The Sporting Life. In commenting on the event the following morning, the unnamed reporter was not, it seemed, particularly enthused. The article’s opening line that ‘the weightlifting in the evening was rather slow’ proved indicative of the report’s evaluation.(15)

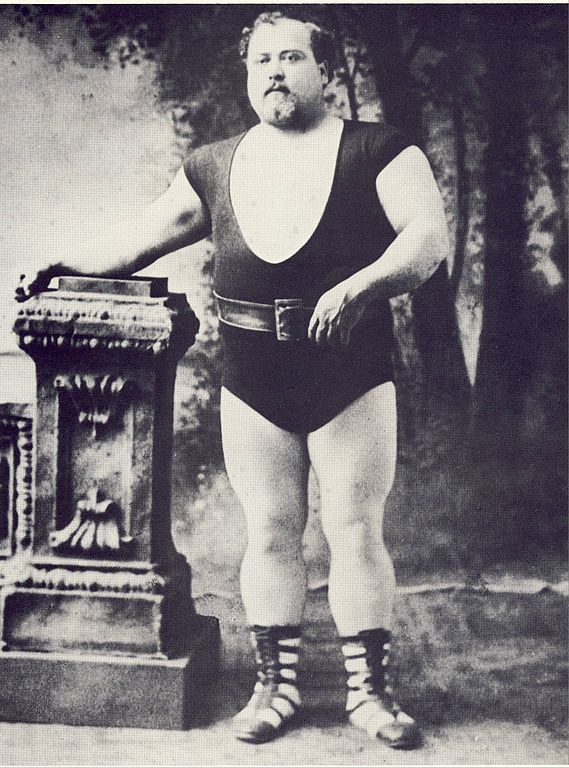

Strongman Louis Cyr

Lack of entertainment aside, the event appears to have been predicated upon two rudimentary lifts. First, the eight competitors were tasked with pressing a 180 lbs. barbell overhead for reps. This was done in a continental style of weightlifting, whereby the barbell was effectively dragged up the body before being pressed. Of the seven men, only two, Pfan and Francoise, executed the lift. The rest of the contestants needed to lower the weight on the bar before doing ‘the trick cleanly.’(16)

The second lift was described as ‘dead-weight lifting.’ While there is no further explanation of this exercise, we can, at the very least, assume with some confidence that it involved lifting a weight someway from the ground.(17) Once again many of the lifters were said to have ‘showed up very poorly.’ Given this was an era when strongmen like Louis Cyr and Eugen Sandow were reportedly lifting hundreds of pounds, it is comforting to read that the max weight in this event was 180 lbs., which was lifted for reps by only a handful of contestants.

The results of all this?

While Zafanau, Francos and Pfan came third in the barbell events, the winner over the course of two days was E. Lawrence Levy. Levy, who declined to compete in the barbell event, had dominated the dumbbell event two days prior. Because the point scoring was cumulative across both disciplines, Levy was declared the winner.(18) It was not the most satisfying of results and as Bonini demonstrated, contributed to a series of attempts to overhaul the rules and scoring of weightlifting competitions.(19)

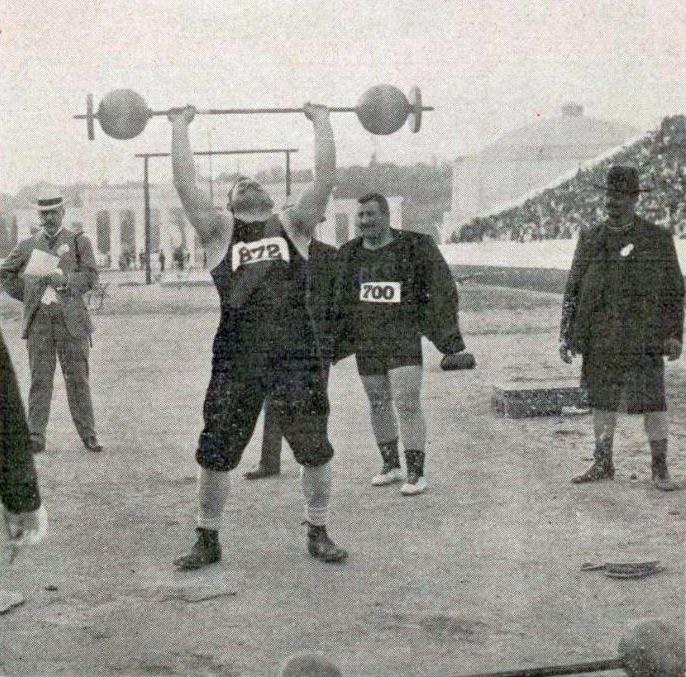

Weightlifting at the 1906 Olympics

The Aftermath

On the face of it, Astley’s contests had not, despite his obvious enthusiasm, been particularly well run. While the dumbbell events garnered a great deal of attention, the barbell contest, the contest we’re interested in, barely made a dent in British newspapers. Did this matter to dedicated lifters? Not one bit.

In September 1891 another barbell competition was held, this time in Vienna. Unlike the March contest, which was noticeably missing some of the better known lifters of the time, the Vienna show welcomed the elites of the lifting world like Franz Stohr and Wilhelm Turk, both of whom held several unofficial world records.(20) Back in Britain, weightlifting continued to progress through the Vaudeville stage where men like Sandow, Levy and a host of others competition against one another in dumbbell and barbell lifts.(21)

In 1896, weightlifting was included in the first Olympic program in Athens. E. Lawrence Levy acted as a judge while Launceston Elliot competed and secured a gold. The 1891 contest thus fed into this later Olympic show. While the first Olympic contest was, like Astley’s show, a very haphazard affair, it was a start. By the 1904 Games, barbells were included in the Olympic games and although the sport’s popularity briefly waned, Olympic weightlifting events with barbells and weight categories were introduced in 1920.(22) They’ve continued to be a mainstay in the Games ever since.

While it would be an overstatement to link Astley’s contest directly to the emergence of Olympic weightlifting, it nevertheless helped to lay the groundwork. This at least, was the opinion of the International Weightlifting Federation, which said as much in the late 1980s during a study of the sport’s evolution.(23) Examining Astley’s contest in detail, it is easy to see why. Although domestic competitions had emerged, Astley’s was one of the first to welcome international weightlifters. It included a focus on barbell lifting and despite the paltry number of reports, it did nevertheless garner some deal of media attention.

As a founding moment, the 1891 contest serves as a great reminder that weightlifting’s evolution was not a clean and straightforward affair. Rather it should be viewed as a series of efforts, successful or otherwise, to popularize the cleaning, pressing, jerking and pulling of heavy weights… an admirable goal by any standard.

References

1. David Webster and Doug Gillon, Barbells and Beefcake: Illustrated History of Bodybuilding (Irving, 1979), 1-22.

2. Jan Todd, ‘Strength is Health: George Barker Windship and the First American Weight Training Boom’, Iron Game History, 3, no. 1 (1993), 5-6.

3. David Chapman, Sandow the Magnificent: Eugen Sandow and the Beginnings of Bodybuilding (Chicago, 1994), 79-88.

4. David Webster, The Iron Game: An Illustrated History of Weight-Lifting (Irvine, 1976), 2-23.

5. Josh Buck, ‘Louis Cyr and Charles Sampson: Archetypes of Vaudevillian Strongmen’, Iron Game History, 5 (1998), 18-28.

6. Jan Todd and Michael Murphy, ‘Portrait of a Strongman: The Circus Career of Ottley Russell Coulter: 1912-1916’, Iron Game History, 7, no. 1 (2001), 4-21.

7. Gherardo Bonini, ‘London: The Cradle of Modern Weightlifting’, Sports Historian, 21, no. 1 (2001), 56-70.

8. Ibid.

9. J.R. Lowerson, ‘Cooper, John Astley’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

10. ‘Amateur Weight-Lifting Championship’, The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 31 January (1891), 684.

11. Michael H. Stone et al., ‘Weightlifting: A Brief Overview’, Strength and Conditioning Journal, 28, no. 1 (2006), 50.

12. ‘Sir John Astley’s Weight Lifting Competition’, The Sporting Life, 27 February (1891), 1; ‘Weight lifting Competition’, The Morning Post, 7 March (1891), 3.

13. ‘Sporting Notes’, St. James Gazette, 30 March (1891), 15.

14. ‘Amateur Weight Lifting’, The Sporting Life, 31 March (1891), 4.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid.

19. Bonini, ‘London: The Cradle of Modern Weightlifting’, 63-68.

10. Ibid.

11. Webster, The Iron Game, 22-43.

12. Dave Randolph, Ultimate Olympic Weightlifting: A Complete Guide to Barbell Lifts—from Beginner to Gold Medal: A Complete Guide to Barbell Lifts—from Beginner to Gold Medal (New York, 2015), 9-15.

13. Bonini, ‘London: The Cradle of Modern Weightlifting’ 56.