If you’re new to the gym, training your back can be a little bit like playing a game of Battleship: The muscles are there, but you aren’t exactly sure where — or how to hit them accurately. Without a comprehensive understanding of your own back anatomy, you’re firing on little more than faith.

You can steamroll through set after set of rows or pull-ups and walk out of the gym having accomplished a half-decent back workout, sure. But your time in the weight room is precious. There’s no sense in navigating the waters of your workout without a heading.

Here’s everything you need to know about the anatomy of your back muscles; where they are, what they do and, most importantly, how to train them optimally.

Editor’s Note: The content on BarBend is meant to be informative in nature, but it should not be taken as medical advice. When starting a new training regimen and/or diet, it is always a good idea to consult with a trusted medical professional. We are not a medical resource. The opinions and articles on this site are not intended for use as diagnosis, prevention, and/or treatment of health problems. They are not substitutes for consulting a qualified medical professional.

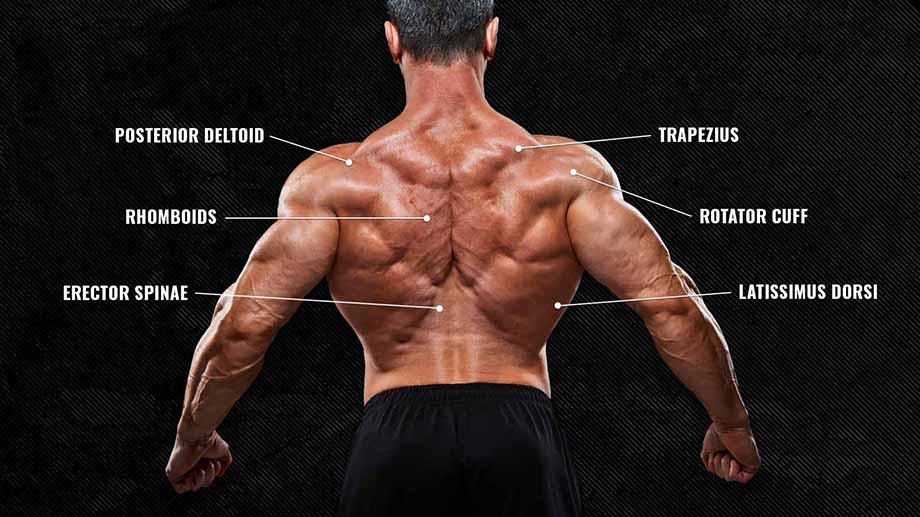

Your Back Muscles

Human anatomy has two primary pillars; structure and function. That is, the design of a given tissue and the action or actions it performs. Some of your back muscles are visible (and trainable), while others lie deeper under your skin.

Here’s an overview of the major muscles in your back that you can identify and effectively stimulate through exercise:

Latissimus Dorsi

Your latissimus dorsi, or lats, are the largest individual muscles in your upper back. They run down the sides of your torso and, when developed through resistance training, contribute to the iconic “V-taper” look.

- Where It Is: Originates on your spine, pelvis, scapula, and lower ribs, and attaches to your upper arm bone.

- What It Does: Adducts and extends your shoulder and upper arm.

As the largest and, debatably, strongest muscles in your back, your lats play a pivotal role in pulling exercises. Any time you bring your upper arm down and back into your torso (a motion called shoulder extension), your lats are doing a lion’s share of the work. Think rows or pull-ups.

Trapezius

Your traps are a large, diamond-shaped muscle that sits squarely in the middle of your upper back. Although your trapezius is considered a single muscle, it has three distinct upper, middle, and lower sections that perform slightly different functions.

- Where It Is: Your upper traps originate on the base of your skull, the middle fibers span your thoracic spine and collarbones, and the lower fibers begin down at the base of your thoracic spine.

- What It Does: Primarily controls motion of the shoulder blade; upper fibers also affect head movement.

Your scapulae, or shoulder blades, sit flush on the back of your rib cage. Your traps primarily work to glide them across your ribs, pinch them back, or rotate them upwards. The trapezius plays an accessory role in back exercises like rows or pull-ups, but is brought center-stage when performing shoulder isolation exercises like shrugs.

Rhomboids

With so much free movement available to your shoulder joint, your body relies on a host of muscles to control and articulate the motion of your shoulder blades. Your rhomboids work closely with other muscles in your back to help stabilize your shoulders.

- Where It Is: Your rhomboids connect from your thoracic and cervical vertebrae to your scapulae.

- What It Does: Primarily performs scapular retraction.

Your rhomboids lie underneath the middle fibers of your traps and work synergistically with them; think of your rhomboids like an anchor. They contract hard to lock your shoulder blade in position, allowing other muscles to contract.

[Read More: The Complete Guide to Pre-Workout Supplements]

In order for your lats to pull your arm toward your body during a row exercise, your rhomboids must be strong enough to hold your shoulder blade motionless as you transfer force across your skeleton.

Posterior Deltoid

Technically, the back third of your shoulder muscles is distinct from the musculature of your back itself. However, most folks consider the rear deltoid — a small, acute muscle on the back of your shoulder — part of the back from a training perspective. This little muscle has a tremendously important job keeping your body moving.

- Where It Is: Originates on the shoulder blade and inserts on the very top of your upper arm bone.

- What It Does: Contributes to abduction of the arm and external rotation of the shoulder.

Your posterior deltoid is the smallest and weakest of the three shoulder muscles. When it comes to back training, though, it has an essential role. Your rear delt helps abduct your arm, drawing it outward and behind you (think a swimmer performing a breast stroke).

It also aids in external rotation of the shoulder; raising and “opening up” your arm, like when you perform a front double biceps bodybuilding pose. In this way, your rear delt also fights against poor posture by holding your shoulder back and keeping your torso extended.

Rotator Cuff

When you hear “rotator cuff,” you probably think “shoulder.” However, your rotator cuff isn’t one individual muscle: It’s a cluster of small tissues that enwrap the glenohumeral joint, the junction between your arm and your torso. Think of these four upper back muscles — the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis — as critical infrastructure.

- Where It Is: The various muscles of the rotator cuff cover the shoulder blade and insert deep within the glenohumeral joint.

- What It Does: Mainly stabilizes the head of your upper arm bone within your shoulder socket. Also contributes to shoulder internal and external rotation.

Essentially, your rotator cuff helps hold all the anatomical stuff together. Since it is a cluster of muscles, you can train your rotator cuff with (lightly) loaded exercises that challenge rotation around the shoulder itself.

Erector Spinae

Of all the muscles within your back, your erector spinae have, perhaps, the most important job: They hold your body upright. The erector spinae are technically three individual tissues that span your entire vertebral column — the spinalis, longissimus, and iliocostalis muscles.

- Where It Is: Your erector spinae originate down on your pelvis and insert throughout your spine.

- What It Does: Maintains rigidity and alignment within your vertebral column and holds your torso upright.

Practically speaking, the erector spinae is synonymous with the lower back. That section bears the most load when you’re performing daily tasks, particularly anything that requires you to bend or hip hinge. Think everything from grabbing an object off the floor to performing a heavy deadlift.

There Are (Many) More

Note that this list is not completely exhaustive. Your back is chock-full of distinct muscles, each with specialized roles and important duties. However, most of them aren’t visually noticeable, much less practically trainable in the gym. Think of the tissues outlined above as the “A-Team” of your back.

The Best Back Exercises

Information is only half the battle. All the anatomical wisdom in the world won’t do you much good in helping you reach your fitness goals if you don’t know how to apply it. To guarantee that you’re training your back properly, start by incorporating a few of these selections into your workout routine:

Overall — Bent-Over Barbell Row

A good back exercise allows the major muscle groups to safely and efficiently perform their primary anatomical functions. Your lats and traps are strong pulling muscles, while your erector spinae muscles are fantastic at holding your spine motionless in space.

[Read More: The Best (and Worst) Bodybuilding Exercises to Cheat Your Form On]

The barbell row allows you to train both of those qualities simultaneously. It’s a phenomenal all-around back-builder for both increasing strength and building muscle.

How to Do It

- Stand upright with a close stance, holding a barbell loosely against your thighs with a close, overhand grip.

- Hinge at your hips; unlock your knees and push your butt backwards. Tip over at your torso and allow the bar to glide down your thighs until it hangs freely under your shoulder.

- Once your torso is roughly parallel to the floor, inhale and brace your core. Feel tension throughout your posterior chain.

- Initiate the row by pulling your shoulders back, then follow through with your arms.

- Pull your elbows up until your upper arms are tucked snugly against your torso.

Coach’s Tip: Think about putting your elbows into your back pockets to activate your lats.

For Lats — Seated Cable Row

Your lats are versatile; any multi-joint back exercise you perform will work them well enough. However, to emphasize your lats specifically, you’ll need to limit the contribution of your traps and take your lower back out of the game as well.

The seated cable row shines here. Sitting down, your erector spinae needn’t work hard to bear weight. The seated row also aligns well with the fibers of your lats, giving them ample leverage and reducing the role your traps can play.

How to Do It

- After adjusting the pin in the plate stack to an appropriate level of resistance, sit down on the seat of the row station.

- Place your feet against the footrests with bent knees and grab your handle of choice. If you’re unsure of which different row grip to choose, opt for a close-grip, neutral or overhand handle.

- Scoot your butt back and straighten your legs to pull the weights off the stack. Allow the cable to pull your arm forward.

- From here, brace your core to maintain a stable, vertical torso. Avoid leaning forward or backward.

- Then, row the handle toward your body by driving your elbows back behind you until your upper arms are aligned with your trunk.

Coach’s Tip: Avoid leaning backward as you row. This will reduce the leverage of your lats and add your lower back into the mix.

For Traps — Kelso Shrug

Your traps have three distinct regions, each with their own primary duty. This necessitates a unique approach to training. Shrugs shine for developing your upper traps, but tend to neglect the middle and lower regions.

[Read More: The Gymgoer’s Guide to Whey Protein]

Simply changing the angle of your torso largely alleviates this issue. Lying on an inclined surface for the Kelso shrug will encourage your middle and lower traps to get involved with moving your shoulder blade dynamically.

How to Do It

- Grab a pair of medium-to-heavy dumbbells and lie chest-down on a bench set between a 45 and 60-degree angle.

- Plant the balls of your feet firmly on the ground behind you and allow your arms to hang loose down on either side of the bench, weights in-hand.

- From here, contract your traps to pull your shoulders up and back in a shrugging motion, without bending your elbows at all.

- Pause for a beat at the top of each rep before lowering the weights back down.

Coach’s Tip: One helpful cue here is to think about putting your shoulders behind your ears.

For Rhomboids — Band Pull-Apart

You don’t need to work with a lot of weight to isolate a small pair of muscles like the rhomboids. You do, however, need to ensure that they’re doing most of the work. It’s all too easy to turn a rhomboid exercise into a trap exercise.

You can zero in on your rhomboids by exploiting their function: Isolate the motion of scapular retraction. Externally rotate your shoulders with an underhand grip to take your traps off the table (partially), and keep your arm straight to reduce lat or biceps engagement.

How to Do It

- Grab a resistance band with a supinated, underhand grip, and stand upright with your feet under your hips.

- Hold the band aloft in front of you with your arms parallel (to each other and the floor) and straightened at the elbow.

- From here, pull the band apart as if you were going to tear it in half by drawing your arms out to the sides and squeezing your shoulder blades together.

- Pause for a moment when the band is fully stretched and your arms form a straight line through your torso.

Coach’s Tip: To properly involve your shoulder blades, think about trying to pinch a penny between them as you stretch the band.

For Posterior Deltoids — Face Pull

Heavy rows or weighted pull-ups require stable shoulders, true enough. However, for your rear deltoids, large compound exercises won’t do enough, as your posterior delts tend to contract isometrically (as in, without actually moving) and not bear much resistance.

To isolate your rear delts, you need to play to their strengths. Particularly, external rotation of the shoulder. The face pull is easy to perform and will absolutely thrash your upper back in the process.

How to Do It

- Set a cable fixture around the height of your collar bones and attach a rope handle to it.

- Grab the rope such that the ball of each end is on the outside of your hand.

- Step back to pull the cable taut and allow your arms to stretch out in front of you.

- Begin the face pull by drawing your shoulders back and pulling your elbows back and out to the sides.

- As you pull, externally rotate your arm; think about “opening up” and revealing the insides of your biceps.

- At the end of each repetition, your arms should form a “U” shape.

Coach’s Tip: If you’re into bodybuilding, think about performing a front double biceps pose while you do the face pull.

For the Rotator Cuff — Side-Lying Kettlebell Overhead Hold With Rotation

The musculature that creates your rotator cuff is strong but delicate. Many small tissues account for the large freedom of movement you enjoy with your shoulder. From a training perspective, this means having to get a little creative with your exercise selection.

[Read More: Best Supplements for Muscle Growth]

One of your rotator cuff’s principal duties is to regulate how much internal and external rotation you take your arm through, particularly against resistance. It’s hard to isolate this demand through conventional back exercises, so you’ll have to get down with a kettlebell instead.

How to Do It

- Lie on the floor on your side. Hold a light kettlebell bottoms-up in your hand and reach toward the ceiling.

- With your arm straight and perpendicular to the floor, slowly twist your arm around as far as you comfortably can.

- The angle of your arm never changes; think of rotating a motionless cylinder in space.

Coach’s Tip: Holding the kettlebell with the bell itself above your hand will increase the stability demand and challenge your rotator cuff.

For Lower Back — 45-Degree Back Extension

Despite what you may have heard in the past, it is perfectly safe to train your lower back directly as long as you maintain good form and load your body properly. Your lower back gets plenty of isometric training through exercises like the deadlift, bent-over row, or squat.

To really strengthen it, though, you should include some dynamic isolation work in which you actively curl and straighten your spine.

How to Do It

- Set yourself into the back extension station with your feet firmly planted against the footrests. The thigh pad should come up just to the top of your legs, allowing you to bend at the waist uninhibited.

- Extend your back to form a straight line from your head down to your feet. You can cross your arms over your chest, or hold a small weight in your hands.

- Bend at the waist and slowly drop your torso down until it is perpendicular to your legs.

- As you descend, gently round your spine over until there’s a slight curve in your back.

- Reverse the motion, uncurling your spine, and using the strength of your lower back to return to the starting position.

Coach’s Tip: If you’re new to direct lower back training, start by working with just your body weight.

Back Training Tips

The gulf between “acceptable” and “optimal” back training is vast. With so many moving parts in play, it pays dividends to know not only how to perform your back workouts properly, but how to squeeze them for all they’re worth. Keep these tips in mind before your next session and see for yourself:

Use Lifting Straps

Your back muscles — particularly your lats and traps — are large, strong, and can tolerate a lot of heavy loading. However, you can only row, shrug, or pull a weight if you can hold onto it in the first place.

You may find that your grip strength limits your ability to perform certain back exercises to their fullest potential. The small muscles in your forearms might tap out on a heavy set of shrugs long before your traps are ready to call it quits.

If your grip is a limiting factor, work with a pair of lifting straps during your heaviest back movements, such as rows, shrugs, or deadlifts. This will ensure that all that valuable tension and stimulation goes exactly where it belongs. And, if you’re concerned about losing out on grip strength, you can always train it separately.

Find the Right Angle

All back muscles originate and attach in the same location. However, your unique anatomical structure differs slightly from everyone else. Small discrepancies in the exact attachment site of your lats onto your upper arm, for instance, will change how they absorb and create force.

In real-world terms, this means that you should fiddle with the setup and execution of back exercises until they “align with your structure.” This could mean taking a very slightly wider grip for rows, or setting a cable fixture a bit higher or lower than your gym partner’s.

Small tweaks can add up to a lot of value gained during a back workout. You should, of course, master the default form of an exercise before modifying it.

“Tuck for Lats, Spread for Traps”

You can row just about any type of weight; a barbell, a pair of dumbbells, a cable attachment, and so on. You can also get specific about how you grip that weight in the first place. Most importantly, your grip of choice will bias certain back muscles more than others.

The angle of your upper arm relative to your torso will encourage you to use scapular muscles like your traps and rhomboids (if your arm is perpendicular to your body), or your lats if your arm is tucked tight to your side. (1)(2)

[Read More: The 5 Best Lower Lat Exercises for a Denser Back]

This isn’t a hard and fast rule, but it’s a good way to direct tension where you want it to go. If you want to strengthen your lats in particular, row with a medium or narrow grip and an overhand or neutral hand position. To emphasize your yoke, widen your grip and flare your arms.

Start Broad, Then Get Specific

How you order your exercises during a workout affects both the quality of your performance and the results you get. Many of your back muscles provide supportive, auxiliary roles; they stabilize your shoulder capsule or lumbar spine while you move heavy weights.

During a back workout, the last thing you want to do is exhaust those supportive structures first, and then try to lift heavy afterwards. As such, your best bet is to perform large, compound or free-weight exercises first, then follow up with isolation moves after.

For example, a good back workout with well-sequenced exercise selections might look like this:

- Deadlift: 3 x 5

- Barbell Row: 3 x 8

- Wide-Grip Pulldown: 2 x 12

- Band Pull-Apart: 2 x 20

Working from “big” to “small” guarantees you hit every important muscle in your back without compromising your strength or technique along the way.

Your Takeaways

Your back is an intricate web of muscle tissue. To train it properly, you need to understand how it all fits together — literally.

- There are dozens of individual muscles in your back, but a handful steal the show.

- Your lats, traps, rhomboids, rear delts, rotator cuff, and lower back are among the major trainable muscles in your back anatomy.

- Pulling exercises train these muscles, though your technique and equipment of choice will affect which among them bears the most load.

- A good back workout utilizes both compound and isolation movements, as well as a variety of different equipment.

More Training Content

- Do Different Row Grips Really Matter?

- The Best Bodybuilding Back Workout for Your Experience Level

- How to Properly Lat Spread Like a Pro Bodybuilder

References

- Signorile, J. F., Zink, A. J., & Szwed, S. P. (2002). A comparative electromyographical investigation of muscle utilization patterns using various hand positions during the lat pull-down. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 16(4), 539–546.

- Andersen, V., Fimland, M. S., Wiik, E., Skoglund, A., & Saeterbakken, A. H. (2014). Effects of grip width on muscle strength and activation in the lat pull-down. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 28(4), 1135–1142.

Featured Image: ThomsonD / Shutterstock