We live in a technological age, and the exercise machines being designed and manufactured today are better than ever. But your muscles were designed by evolution to overcome the pull of gravity rather than to work against machine resistance, so the biggest gains you will make in building size and strength will come from pumping iron…rather than by exercising on machines.

– Arnold Schwarzenegger, 1998 (1)

The modern gym would be a very strange thing for our physical culture forbearers. For men and women of yesteryear, namely those in the late nineteenth and early-twentieth century, working out in a gymnasium usually revolved around dumbbells, barbells and other weighted objects like kettlebells or Indian clubs. For those without access to gymnasiums, makeshift weights were used ranging from old farming equipment to heavy stones.(2) The idea that you would use a machine to exercise was not entirely far fetched but the popularity of such things paled in comparison to good old fashioned steel weights.

Fast forward roughly a century and times have certainly changed. Nowadays, any gym worth its salt boasts an array of shiny devices said to strip away unwanted fat, build copious amounts of muscle, and do it in a relatively short space of time. We have, for want of a better term, become a machine people.

While the rise of CrossFit and the growing popularity of powerlifting has encouraged lifters to return to the basics of free weights, countless lifters use machines as part of their training programs. For certain body parts, such as the calves, old school methods relying solely on dumbbells and barbells can really seem antiquated . For other body parts, like the quads or hamstrings, the use of machines rather than basic barbell exercises is for many, downright sacrilege. With this in mind, we have to ask when did machines infiltrate the gym? Furthermore why did they become so successful?

In answering these questions, today’s post looks at four distinct ‘waves’ of weight training machines, beginning in the 1790s and continuing to this very day:

- Something from Nothing: The 1790s to 1890s

- Sandows, Sergeants and Zanders: A Critical Phase

- The Third Wave: Health Clubs and ‘Do It Yourself’ Machines

- Machines in the Modern Age

As becomes clear, the use, some would say abuse, of weight training machines was indicative of a growing acceptance of weightlifting amongst the general public. Put another way, we can say that machines catered for, and encouraged, a public interested in training their bodies. In a way, weight training machines helped to demystify the practice of working out and make it an acceptable hobby.

Something from Nothing: The 1790s to 1890s

In one of the first examinations of dumbbells, barbells and Indian clubs, historian Jan Todd noted the longevity of weighted objects used for training purposes, dating the first dumbbells to the ancient Greeks (3). Today’s post begins in a far more recent past, beginning with the Gymnasticon in 1797. Possessing possibly the most pompous sounding name you’re likely to encounter in a gym, the Gymnasticon was designed by the physician Francis Lowndes to, in its inventor’s words, ‘exercise the joints and muscles of the human body’ (4).

Seen as both a precursor to the flywheel and the exercise bike, Lowndes’ contraption, shown below, marked an ambitious attempt to strengthen the body in one fluid exercise. While the machine’s resistance was relatively low, it nevertheless marked a pivotal step in the development of future works.

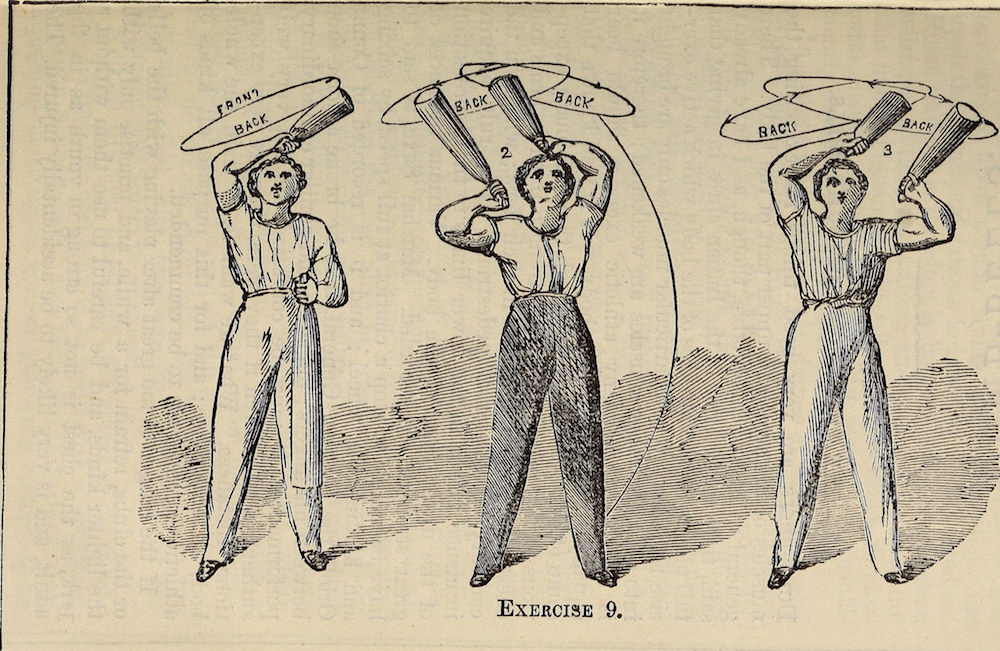

Inspired by the orthopedist, Nicolas Andry, who Todd noted may also have helped popularise club swinging for health, Lowndes’ intentions were almost entirely medical in nature (5). This was an important distinction to make when discussing early health machines. Though the beginning of the nineteenth-century saw rudimentary forms of weight training emerge, most notably in the practice of Indian club swinging, weight training machines for the purpose of health or strength were largely unknown (6). Machines, when and where they existed, were concerned with rehabilitation or the prevention of illness and injury, not strength and athletics.

This emphasis on medical, as opposed to athletic concerns, underpinned the second great innovation, James Chiosso’s Polymachinon. An odd looking device, not too dissimilar to the cable towers found in most modern gyms, Chiosso’s Polymachinon was later accompanied by a small pamphlet detailing its purposes and instructions (7). Thankfully available for free online, the pamphlet made clear the inventor’s intentions by describing the Polymachinon as as ‘an essential branch of popular education, and an invaluable remedial agent in many forms of chronic disease’ (8) In noting a rising interest in gymnastics, Chiosso’s frequent references ‘to hygienic or curative medium[s]’ of exercise pointed once more towards the medical utility of such devices (9).

Chiosso’s prototype dated to 1831, and his machines, as detailed by Carolyn de la Peña, were still in demand in Europe and the US at the mid-century mark (10). Given the very small pool of health inventors during this time, it is remarkable to note that there is little evidence to suggest that Chiosso was aware of Lowndes’ Gymnasticon device (11). What is clear however is that Chiosso’s machine marked a move towards public health. Well aware of his machine’s medical utility, Chiosso was equally interested in encouraging relatively healthy men and women to begin exercising. His device also offered far greater resistance than Lowndes’ Gymnasticon during exercises (12). In other words, the Polymachinon offered greater muscle building potential.

Chiosso, James. The Gymnastic Polymachinon: Instructions for Performing a Systematic Series of Exercises on the Gymnastic & Calisthenic Polymachinon (Walton & Maberly, 1855), preface.

Also emerging during this time was the Health Lift, a machine which mimicked the effects of a harness lift, hip belt squat or heavy rack pull (13). Devised by Dr. George Barker Windship, a Harvard educated physician who was one of the most famous proponents of heavy weight training during the 1860s and early 1870s. As detailed by Todd in a highly readable account, Windship built his frail physique first through gymnastics and then through heavy weight training (14). This interest in building muscle and strength eventually evolved into his patented ‘Health Lift’ machine. With the zealousness of the convert, Windship toured East Coast of the United States, preaching the benefits of his machine at a time when many doubted the usefulness of heavy weight training. This included members of the medical profession, presumably aghast that one of their own believed in heavy resistance training. Based upon a weight lifting machine he used in New York, Windship’s ‘Health Lift’ was briefly ‘THE’ weight lifting machine to use.

Even Windship’s untimely death aged 42, did little to detract from the machine’s popularity. Though the inventor’s demise was credited to heavy weight lifting — remember, doctors were convinced it was terrible for you — his machine, as de la Peña explained, continued to be used well into the 1870s and 1880s (15). The nineteenth-century thus proved a pivotal stage of development.Weight training machines were developed to exercise the entire body and, owing to Windship’s contribution, heavy forms of resistance could be applied.

[Read more from the author: The Fascinating Story of the First Bodybuilding Show.]

While the machines examined above look scarcely familiar to modern gym goers, they were a start, and a good one at that. The late 1890s and early 1900s would see developments progress even further.

Sandows, Sergeants and Zanders: A Critical Phase

Returning to de la Peña’s work on the subject, the late nineteenth and early twentieth-century was a pivotal moment in the history of weight training machines (16).

In the first instance it brought us Gustav Zander, a Swedish physician and inventor whose interest in the body inspired many of the machines we still use today. Concerned more with health rehabilitation rather than muscle building, Zander’s machines, which sought to exercise the entire body, were found in 146 countries by 1906.

Through collaborations with Dudley Sergeant, an influential physical education teacher at Harvard University who himself designed over 50 separate health devices, Zander’s machines were brought to the American public in the early 1900s (17). Now, while de la Peña was right to highlight Zander’s machines were predominantly for the wealthier classes, their influence cannot be underestimated (18). For the first time, individuals were treated to a whole body workout which targeted individual muscles conducted entirely on machines. It was also a sign of things to come.

Writing in the 1970s, Arthur Jones of Nautilus fame, claimed that although he designed his machines before discovering Zander’s inventions, his devices operated on a similar basis (19). Certainly when one views Zander’s machines in 2019, their similarity to leg extension and leg curl machines in particular, is striking.

Now admittedly some of Zander’s devices appear very far fetched, especially those centred on the abdominals. Zander, as his medical background suggests, was interested in health more so than muscularity. Despite this, his machines split the body into component parts, with a machine available for the legs, the arms, the chest and so on. Specialization was occuring.

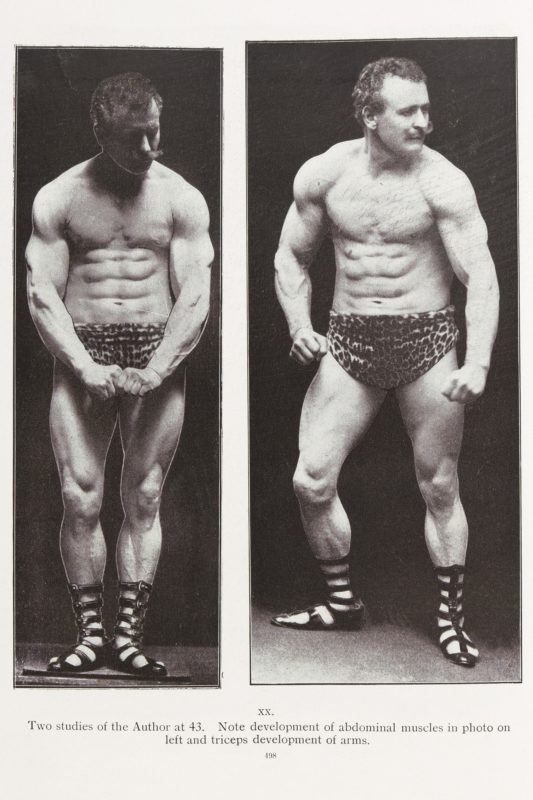

Zander however, was not the only influential figure during this time. Equally important was Eugen Sandow, a man regularly credited as the ‘Father’ of modern bodybuilding. Sandow himself was no inventor, and as Foutch demonstrated, had no medical qualifications whatsoever (20). What he did have however was that ‘star’ power necessary to promote new goods.

[Read more about one of the most influential bodybuilders of all time, Eugen Sandow!]

In the first instance, Sandow promoted the ‘Sandow Developer’, a combination between a pulley and a strand puller that individuals could connect to a door frame and exercise with (21). Invented by a Mr. Whiteley who briefly co-sold the product with Sandow, the Developer was one of the most popular all round exercisers of its day and it inspired a series of copycat devices by other physical culturists, including the always controversial Bernarr MacFadden (22). Sandow, did not however, stop there. Through an enviable insight into consumer interests, Sandow also promoted several other machines, which sadly for him, failed to capture the public’s imagination. This included an ill conceived weight training device for young children. Presented with a life size doll, children would pull at the dummy’s weighted hands and, if sufficient force was applied, would receive a sweet. Described by Chapman as highly fanciful, it nevertheless spoke of a potential for training devices aside from dumbbells and barbells (23).

French postcard showing Sandow’s ‘All in One’ Devices.

The Third Wave? Health Clubs and ‘Do It Yourself’ Machines

Influential as they were, Zander, Sergeant and Sandow shared one rather unfortunate trait: they catered primarily towards the middle and upper classes, specifically targeting those interested in lightweight forms of training (24). Those promoting heavy weight training as expressed in barbells and dumbbells, had yet to produce any machines of their own.

This isn’t to say that the strongmen and women of the early 1900s were not innovators. Both Louis Cyr and Thomas Inch promoted thick grip dumbbells and it is notable that Cyr’s dumbell is still in use in World’s Strongest Man events. Edward Aston sold ‘anti-fulcrum’ barbells in which weight was attached to one side of the barbell only. Apollo, perhaps ahead of his time given the later popularity of sand bags, lifted heavy sacks of flour on stage during his shows (25). Innovations existed but they were niche and far removed from the general public’s interest.

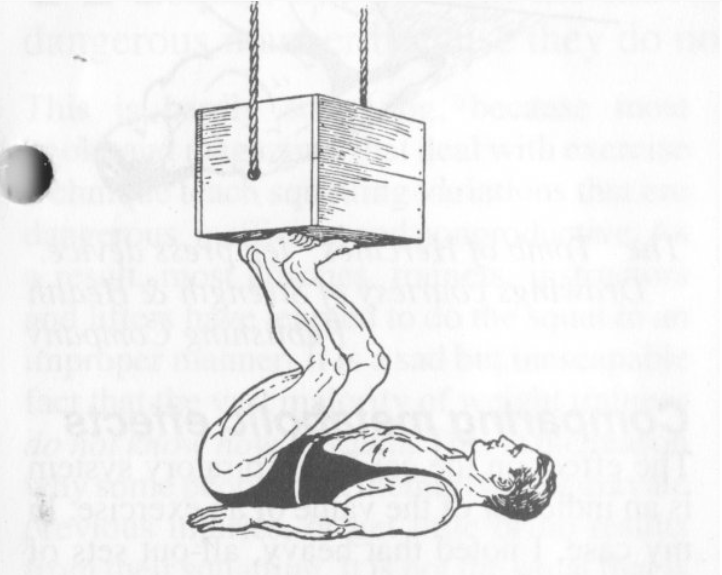

As time went on, and performers began to open their own gymnasiums, matters changed. In New York in the 1930s and 40s, Sig Klein displayed a remarkable ingenuity in designing several machines thought to mimic old strongman lifts (26). Seeking to replicate the inverted leg press used in many performances, Klein created his own device, modeled on modelled on a Tomb of Hercules strongman trick. His invention was later improved upon by another physical culturist, George F. Jowett, whose 1931 work, Moulding Mighty Legs featured a Jowett Leg Press.

Why Klein is important in this story is that he published images of his machines through books, correspondences, and his monthly magazine, Klein’s Bell. The history of these devices is much harder to track down, but it is reasonable to suggest that such innovations undoubtedly occurred in gyms across the US and Europe during this time. Thankfully at least one health fanatic, in the form of Jack LaLanne, was more than happy to share his story. As detailed previously on Barbend, LaLanne’s entrepreneurial spirit saw him open his first gymnasium in the mid-1930s. Still a far cry from the modern gym, LaLanne’s well publicised efforts highlighted a space which combined traditional free weights with cables and rudimentary chest, leg and back machines. While Jack falsely claimed to have invented many of these devices, a point made even more fanciful given what we’ve discussed, his pioneering gym marked a pivotal step in the ‘machine age.’

‘The War of the Gym Machines’

From LaLanne and Klein, the fitness community moved on, albeit slowly. The Second World War resulted in the production of new free weight devices such as the ‘Iron Boot’ or ‘Swingbell’, but new machines were few and far between (27). In short, they were seldom used and rarely improved upon — but this situation was not to last.

Midway through the 1950s, new forms of training and by proxy, new devices began entering the gym floor. One instance of this came when the previously mentioned Jack LaLanne and Rudy Smith met for dinner and co-created the Smith Machine (28). Produced in the end by Smith, and publicised through Vic Tanny’s highly successful commercial gyms, the Smith Machine was in part borne from LaLanne’s assertion that some form of machine was needed to safeguard members of the general public from injury.

Other innovators, at least in the US, included Harry Smith and Leo Stern. According to Randy Roach’s historical account, both men, who ran successful gymnasiums during the 1950s, created a series of bespoke machines with the help of the local foundry (29). Gym goers to Smith’s South Tampa gym thus had access to a makeshift leg curl and inverted leg press. Stern’s gym supposedly boasted leg extensions, calf machines and numerous other weight lifting goodies. This is to say nothing of Vince Gironda’s gym which boasted equipment designed according to Vince’s own, highly personalised, instructions. Perhaps best known for the birth of the preacher curl, Vince’s Venice Beach gym, which welcomed bodybuilders, Hollywood actors and the regular public, had numerous pulleys and machines for trainees (30). Like Joe Gold’s nearby facility, the equipment had been designed with the bodybuilder in mind (31).

The Smith machine and the devices found in dedicated gymnasiums spoke of a new interest in health and fitness, an interest was shared by Harold Zinkin. Prior to the 1950s, Zinkin was more synonymous with the bodybuilding scene than anything else. Voted Mr. California in 1941 and runner up in the 1945 Mr. America contest, Zinkin ran a series of gyms during the 1950s aimed primarily at the general public. It was for this reason that Zinkin created his own multi-stack weights machine in 1957. Soon produced under the name Universal Gym, Harold’s first machine allowed users to quickly switch between weights by simply moving a pin up or down a stack (32). It also combined several stations into one stationery machine so that lifters could train their back before moving two steps to the left and hitting their chest and so on.

It was simple but hugely influential as it changed the way gym owners thought about their space. Why bother buying several separate machines, which required a huge amount of floor space and maintenance, when you could purchase an ‘all in one’ machine? A decade after his first prototype, Zinkin’s Universal machines spread throughout the United States and further afield. Zinkin sold the company for several million dollars in 1968 but remained as CEO for another ten years. It is true that others were producing machines at this time, but Zinkin’s devices were for many, the undisputed favorite for both the dedicated gym goer and the weekend warrior (33). That was, until the arrival of the ‘Blue Monster.’

The ‘Blue Monster’, as intimidating as the name might be, was nothing in comparison to its creator, Arthur Jones — the man responsible for Nautilus machines. A member of the US Navy during the Second World War, Jones spent the 1950s and 60s flying planes in Africa for his wildlife program, transporting exotic animals and engaging in a steady amount of hunting (34). In addition, Arthur produced several entertaining but far from high brow movies and even featured the legendary Bill Pearl in his 1958 horror movie ‘Voodoo Swamp’ (35). Throughout all of this he was, in the kindest possible words, a strong willed man.

It was this one focused nature which ultimately spurred on Jones’ strength building empire. To return to the ‘Blue Monster’, produced in the 1960s, Jones’ creation represented a another iteration of the multi-station device popularised by Zinkin. Unlike Zinkin’s device however, Jones’ ‘Nautilus’ machines relied upon chains, cams and sprockets, which ensured that tension was placed on the muscle throughout the entirety of the rep.

Premiered at a Mr. America contest, Jones’ Nautilus devices swept the bodybuilding and fitness community by storm (36). Combined with Jones belief in High Intensity Training, the man undoubtedly changed the landscape of gym machines. His machines emerged in High School gyms, NFL training facilities and a series of machine only gyms throughout the USA (37). In 1973, Jones and Casey Viator claimed to have gained 15 and 63 pounds of muscle respectively through a month’s training on the Nautilus machines. While the ‘Colorado Experiment’, as the trial become known, has undergone significant criticism, its seemingly miraculous results strengthened the public’s belief in the validity of weight training machines (38). It was for this reason that the Washington Post published an article in 1977 entitled ‘The War of the Gym Machines’ (39). Spurred on by Zinkin and Jones, these new devices became a mainstay in gyms in the United States and further afield. Unlike the specified, and somewhat exclusive, machines found in dedicated bodybuilding gymnasiums, Zinkin and Jones’ devices could be used by almost anyone… and they were!

[See where we’re at today in our list of the best home gyms!]

Machines in the Modern Age

By the 1980s, weight training machines were a normal occurrence for gym goers. In fact, many with an interest in health and fitness began to use them en lieu of free weights. Sam Fussell’s wonderful biographic account of his bodybuilding pursuits during this time, “Muscle,” noted his initial reluctance towards free weights and his almost instinctual attraction to machines. Machines, at least in Fussell’s mind, were a far less daunting thing to master (40). Since Fussell’s time, machines’ popularity have increased through the emergence of circuit training classes such as the Curves franchise for women in 1992 (41).

While debates about free weights versus machines continue to plague the fitness industry, a noticeable trend in recent years has been the emergence of far more specialized machines geared directly toward the serious trainee. From the early 1990s the legendary Lou Simmons of Westside barbell began to sell the ‘reverse hyper machine’, an ingenious device designed to strengthen the lower back. Simmons’ invention has been followed by specialised glute machines, said to mimic the hip thrust exercise so in vogue these days, and a litany of new variations of the chest press or seated row.

While major advances in this field came in the mid-twentieth-century, progress and innovation has continued. This is best typified of course in the shake weight, a machine so inexplicably comical, it must do something worthwhile…

[Read More: The Most Effective Workout Splits, Created by Our Experts]

Conclusion

Looking through this brief history of weight training machines highlights two important points. First that many weight training machines were borne from genuine medical concerns surrounding the body. While the Polymacion or Gymnasticon were indeed muscle building devices, their primary focus was on overall health and wellbeing. It’s never any harm to remember the holistic impact that fitness can have.

Second, and perhaps more significantly, the popularity of machines mirrors that of health and fitness more generally. As weight lifting and going to the gym became more and more acceptable, members of the general public needed quick, less strenuous and more specified forms of training. It was here that the Zinkins and Jones of the world came into their own. Alongside machines for the general public, growing numbers of bodybuilders and powerlifters resulted in newer and highly specialised machines being produced.

For lifters today, the variety, depth and quantity of weight training machines has never been higher. So before we descend into another argument surrounding the usefulness of the Smith machine, leg extension or even the adductor machines, we should take a moment and reflect upon the long line of innovations that brought us to this point.

Featured image via @pullsh and @prof.ariana.braga on Instagram.

References

1. Schwarzenegger, Arnold, and Bill Dobbins. The new encyclopedia of modern bodybuilding. (Simon and Schuster, 1998), 97.

2. Heffernan, Conor. ‘Like a Rolling Stone: Stone Lifting in Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Ireland.’ Playing Pasts.

3. Todd, Jan. “The strength builders: a history of barbells, dumbbells and Indian clubs.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 20.1 (2003): 65-90.

4. Bakewell, Sarah, “Illustrations from the Wellcome Institute Library: Medical Gymnastics and the Cyriax Collection,” Medical History 41 (1997): 487–495.

5. Ibid; Todd, Jan. Physical culture and the body beautiful: Purposive exercise in the lives of American women, 1800-1870 (Mercer University Press, 1998), 93.

6. Heffernan, Conor. “‘Born swinging’: Tom Burrows and the forgotten art of endurance club swinging.” Sport in History(2018): 1-29.

7. Chiosso, James. The Gymnastic Polymachinon: Instructions for Performing a Systematic Series of Exercises on the Gymnastic & Calisthenic Polymachinon (Walton & Maberly, 1855).

8. Ibid, 9.

Ibid.

De La Peña, Carolyn Thomas. The body electric: how strange machines built the modern American (NYU Press, 2003), 33.

Ibid, 34-37.

Ibid.

Paul, Joan. “The health reformers: George Barker Windship and Boston’s strength seekers.” Journal of sport history 10.3 (1983): 41-57

Todd, Jan. ““Strength is Health”: George Barker Windship and the First American Weight Training Boom.” Iron game history 3.1 (1993): 5-6.

De La Peña, The body electric, 45-50.

De la Peña, Carolyn. “Dudley Allen Sargent: Health machines and the energized male body.” Iron Game History 8.2 (2003): 3-19.

On Zander more generally see Terlouw, T. J. “The rise and fall of Zander-Institutes in The Netherlands around 1900.” Medizin, Gesellschaft, und Geschichte: Jahrbuch des Instituts fur Geschichte der Medizin der Robert Bosch Stiftung 25 (2007): 91-124.

De la Peña, “Dudley Allen Sargent.”

Brian D. Johnston, ‘An Interview with Arthur Jones’. ArthurJonesExercise.

Foutch, Ellery E. Arresting beauty: The perfectionist impulse of Peale’s butterflies, Heade’s hummingbirds, Blaschka’s flowers, and Sandow’s body (University of Pennsylvania, 2011), 171-174.

Morais, Dominic G. “Branding Iron: Eugen Sandow’s “Modern” Marketing Strategies, 1887-1925.” Journal of Sport History40.2 (2013): 193-214

MACFADDEN, Bernarr Adolphus. Muscular Power and Beauty: Containing Detailed Instructions for the Development of the External Muscular System to Its Utmost Degree of Perfection.[With Illustrations.] (Physical Culture City, NJ; London, 1906).

Chapman, David L., Sandow the Magnificent : Eugen Sandow and the beginnings of bodybuilding (University of Illinois Press, 2006), 168-175.

De la Peña, “Dudley Allen Sargent.”

Much of this is covered in Kent, Graeme. The Strongest Men on Earth: When the Muscle Men Ruled Show Business (Biteback Publishing, 2012).

Gaines, Charles, and George Butler. Pumping iron: The art and sport of bodybuilding (New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1974), 101-104.

Heffernan, Conor, ‘The Lost Art of Swingbell Training.’ Physical Culture Study. Hoffman, Bob. Bob Hoffman’s Simplified System of Barbell Training (York Barbell Company, 1941), 4-8.

Pollack, Benjamin Richard. Becoming Jack LaLanne (University of Texas, Diss. 2018), 110.

Roach, Randy. “Muscle, Smoke & Mirrors, Vol. 1 (Bloomington, 2008), 242-244.

Ibid.

Ibid, 375-380.

Rao, V.K., Physical Education (Delhi, 2007), 243-245.

Associated Press, ‘Harold Zinkin Sr., Fitness Pioneer, Dies at 82.’ The New York Times, 26 Sept., 2004.

Bill Pearl, ‘Arthur Jones: An Unconventional Character’, Iron Game History, March (2005): 17-22.

Ibid., 18.

Martin, Andrew. ‘Arthur Jones, 80, Exercise Machine Inventor, Dies.’ The New York Times, 30 Aug., 2007

Roach, Randy. “Muscle, Smoke & Mirrors, Vol. 2 (Bloomington, 2011), 245-246.

Ibid., 420-433.

Moore, Timothy, ‘The War of the Gym Machines: Muscles Caught in the Middle’, The Washington Post, 24 Mar. 1977.

Fussell, Samuel Wilson. Muscle: Confessions of an unlikely bodybuilder (Open Road Media, 2015), Chapter Two.

Hentges, Sarah. Women and fitness in American culture (McFarland, 2013), 225.