A cultural trope exists that police officers are often out-of-shape doughnut-loving public servants. The kinds of characters you may have chuckled at in movies like RoboCop 3 and Die Hard, or animated shows like The Simpsons, and the literal doughnut that is a police sheriff on The Amazing World of Gumball. However, real-life law enforcement has to maintain their physical fitness for the rigors of the job, often through varying shift schedules and difficult work-life balance.

Each state has varying fitness standards they hold their recruits to. Still, for those looking to enter the force, you can build a baseline of physical fitness by performing calisthenics, high-volume bodyweight workouts, and pyramid training.

BarBend communicated with several officers and sergeants from the Columbus Police Department (CPD) and the Tactical Rehab and Conditioning Coordinator at the Wexner Medical Center of Sports Medicine at Ohio State University for the training programs that keep them at the fitness level required for their jobs. Let’s break down the kind of fitness it takes to get into law enforcement, how to maintain that physical fitness once you’re working in the field, and the importance of maintaining your mental health to balance the high stress inherent to the job.

Fitness Standards for Law Enforcement

Most police departments nationwide have fitness standards for recruits that include a minimum number of push-ups, sit-ups, and a 1.5-mile run for time, based on age and gender. These are known as the “Cooper Standards,” developed by the Cooper Institute for Aerobics Research in Dallas, TX. Fitness requirements vary state to state, but the foundation of fitness needed to meet the Cooper Standards is the more-or-less the same.

On average, law enforcement officers are typically in better shape than the general population. Despite that, comparative studies have shown that the average fitness levels of law enforcement agencies are not equal across the US. A 2020 study in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research found that female recruits are generally less fit than their male counterparts based on the number of pull-ups and push-ups they can perform. However, that could shift given adequate preparation with the right kind of training. (1)(2)(3)

Pyramid Training

Lead Training Officer at the Columbus City Police Department Remus Borcila shared with BarBend the workouts performed at the Columbus Police Academy (CPA), where classes of 65-70 recruits spend seven months. They are high-intensity pyramid workouts consisting of sit-ups, jumping jacks, wall sits, burpees, push-ups, sit-ups, bodyweight squats, mountain climbers, and a lot of running.

The incentives for recruits excelling in fitness are ever-present. Scoring in the highest of three levels in the annual physical fitness test earns some nice perks like extra paid time off. Scores in additional fitness tests determine seniority and serve as a basis for promotions.

Pyramid training involves increasing the reps in subsequent sets up to a specific target and then decreasing by the same increment to completion. For example, a basic push-up pyramid workout might consist of one push-up in the first set, then two reps in the second set, and so on up to 10 reps. The reps reverse with a set of nine reps, then eight, and so on until the workout is complete. It has been shown to improve muscular strength, muscle growth, and muscle quality — the gradual increase of muscle stimuli makes workouts efficient and can reduce cardiovascular risk factors (4)(5)(6)

Group Training

Pyramid-style workouts for recruits at the CPA are performed in group sessions, partner workouts, and individually. Training as a group has significant mental health benefits and potential physical gains. Training in a group has been shown to significantly decrease perceived stress and increase quality of life compared with exercising alone or not at all. Additionally, training as part of a group may lead to greater exertion during the workout with better perceptions of enjoyment. So you’ll likely work harder and enjoy it more when training with a group. (7)(8)

Here is an example group workout performed by recruits at the CPA:

- 30 sit-ups

- 40 jumping jacks

- Two-minute wall-sit

- 15 burpees

- 25 push-ups

- 25 sit-ups

- 15 burpees

- 30 squats

One-minute water break, then:

- 15 mountain-climbers

- 40 jumping jacks

- Two-minute wall-sit

- One-minute plank

- 30 sit-ups

- One-minute wall-sit

One-minute water break, then:

- 25 mountain climbers

- 30 sit-ups

- 25 mountain climbers

- 15 push-ups

- One-minute wall-sit

- 25 push-ups

- 20 sit-ups

The workout concludes with a half-mile cool-down run, followed by stretching.

You may have noticed that the entirety of the above workout utilizes bodyweight training. While resistance training is essential for increasing muscle strength, power, endurance, and hypertrophy, bodyweight training has been shown to enhance cardiorespiratory fitness and substantially improve lower-body muscle force. (9)(10)(11)

As a new police officer learning the ropes, there is also something to be said regarding the encouragement from one’s peers. Those who perceive themselves as more physically fit are likely to perform better in fitness-related activities than those who don’t — confidence if your physical fitness for the job matters. (12)

Functional Fitness Training

Once in the force, it is an officer’s responsibility to maintain their fitness — a tall order given the potential for inconsistent work and sleep schedules while maintaining a healthy work-life balance. According to Applied Ergonomics, in 2019, the most commonly reported area of physical discomfort for active-duty police officers was lower-back pain. Much of this is due to wearing a heavily loaded duty belt during a shift. Officers who trade their duty belts for weight-bearing vests — anything to move weight away from the waist — may improve their ergonomics (i.e., sitting position, posture). (13)

A real-world example is Anne Spahr, Police Sergeant of the Kent State University Police, who dealt with chronic back pain due, in part, to the use of traditional gun belts. After polling her colleagues while taking light duty, she proposed a change to replace gun belts with load-bearing vests. Modular Lightweight Load-carrying Equipment (MOLLE) vests were adopted and Spahr’s back problems have since subsided.

While improved ergonomics with updated attire is helpful, it will be limited if officers aren’t fit enough to move with it for hours at a time or don’t know how to bear that kind of load for extended periods correctly. That’s where functional fitness training can help. Research suggests a correlation between an officer’s movement patterns and occupational performance. (14) That begs the question, what kind of functional fitness training should law enforcement officers pursue to improve physical performance in the field?

At the CPA, they employ variations of CrossFit® training, which has been shown to maintain the health of law enforcement officers through the first five years of service after graduation. Additionally, similar conditioning programs have been shown to improve the fitness of tactical athletes (more on this later). (15)(16)

Here are a pair of example CrossFit® workouts recruits at the CPA perform:

Modified “Murph”

For time:

- Run one mile

- 100 push-ups

- 100 sit-ups

- 100 squats

- Run one mile

The second-mile run should be about 45 seconds to one minute slower than the first-mile run. During each exercise, recruits must move locations every 25 reps for accountability.

Individual Workouts — Modified “Blake”

Five rounds for time of:

- 35 lunges

- 30 box jumps

- 25 sit-ups

- 20 wall ball squats

- 15 decline push-ups

- Run — three laps around the gym or one lap around the Academy (approx. 1.2 miles)

Physical performance while wearing the load required while on duty has been shown to decrease versus performance while unloaded. That means engaging in this kind of functional fitness training becomes increasingly important to maintain and improve upper-body endurance, lower-body power, and aerobic fitness to offset the hindrance that a duty belt or vest might apply. (17)

Tactical Training

In addition to their physical fitness training, law enforcement officers also engage in combat training to mimic circumstances they may encounter in the field. Chris Kolba, PT MHS CSCS, Ohio State Sports Medicine at Bo Jackson Elite Sports, shared four movements for officers to train:

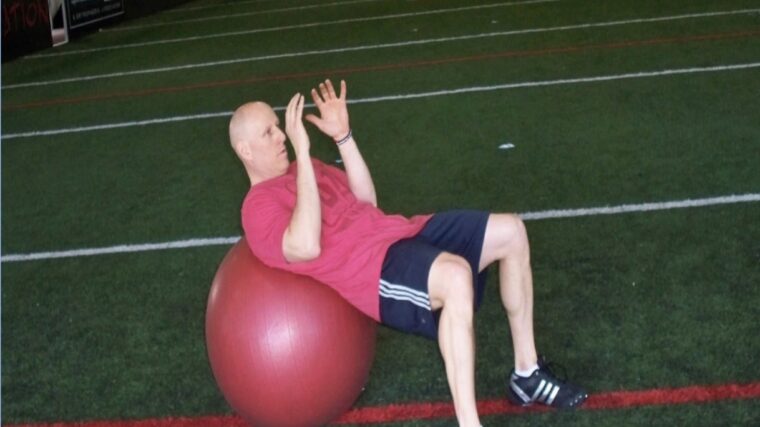

Transition Drill for Ground Fight

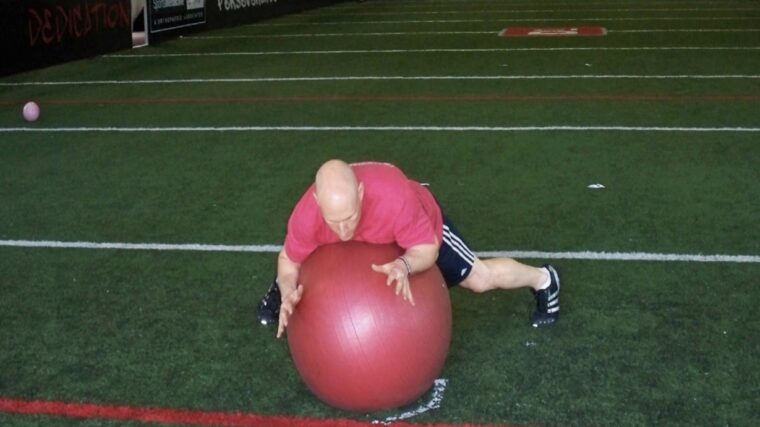

If an officer is grounded on their back during a fight, rotating the body to take side control — as it’s known in Jiu-Jitsu — of the opposition can allow the officer to dictate combat better. To improve this movement, Kolba recommends working rotational power and control on a swiss ball:

With the feet planted on the ground, the move involves generating force with the leg on the side one aims to rotate away from. For this example in the image above, Kolba drives through his left leg and engages his rotational power to roll to his right convert to side control, as seen in the image below:

Control of the body is never lost in the movement; there isn’t any flailing. It is an intentional repositioning for better control to de-escalate the situation.

Blocking

In the event combat is engaged and both involved remain upright, defense is essential with the goal of de-escalation. For this, Kolba trains defense reaction to appropriately respond to the incoming strike and upper extremity impact loading:

Kolba’s assumes a balanced stance and uses his forearms to defend himself. Like the tactical drill above, he maintains control of his body even under pressure.

Suplex Pulls

For circumstances where an officer needs to move or lift someone physically, the suplex pull is the go-to option. Some might know the move from combat sports as a German suplex. However, the difference here is moving the person to a different position, not injuring them.

To build the strength for a suplex pull, Kolba wraps a resistance band around a base on the floor and assumes the grip he would use on a person — one hand gripping the opposing forearm — with a square stance. From there, the pull is up and towards one shoulder as the feet reposition to avoid losing balance:

Working pulls in both directions can build the core and shoulder strength required for the move as well as enhance spacial awareness to know where one intends for the person being lifted to land.

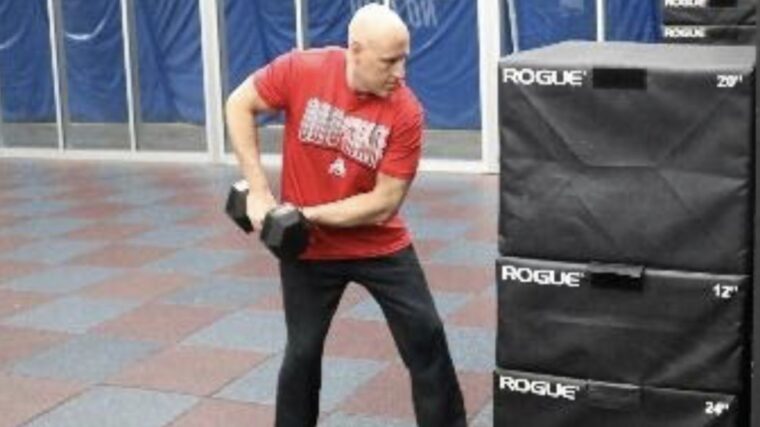

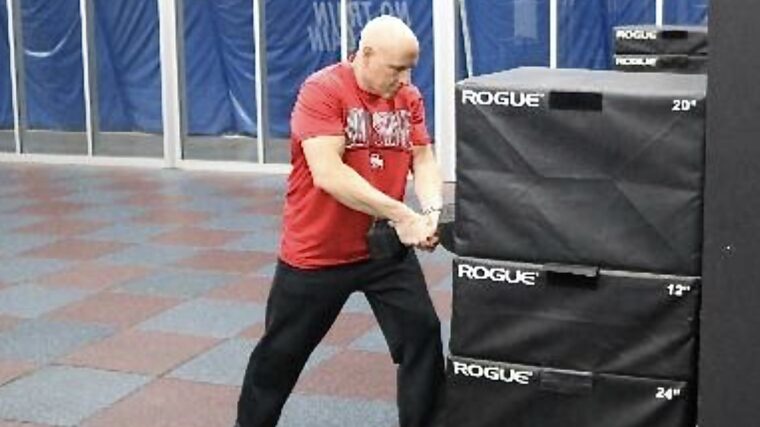

Door Rams

A door ram is precisely as it sounds. An officer swings a ram at a door or a barricade to gain entry to a target location. While this functionally is a rotational swing, there are some subtle nuances in form that Kolba demonstrates below using a dumbbell:

His stance, while steady, is not entirely perpendicular to the boxes (representing a door). They are turned closer to a 45-degree angle to allow for the hips to drive the ram to the target as the upper body rotates for additional power.

Unlike swinging a baseball bat, where the rotation continues through the swing, Kolba’s shoulders are square to the target upon full extension as he drives through with his right hip. This will allow for better control of the ram so that its swing path is directly in line with the target rather than at an awkward angle that could compromise grip.

Training Alternatives

The most common injuries reported by law enforcement that Kolba encounters involve the shoulders, back, and knees. To train around these injuries so they have the requisite time to heal, Kolba recommends exercises that put less stress on the aggravated area while still gaining the strength benefits of the training.

For example, if an officer suffers from shoulder pain, rather than performing a standard bench press, Kolba might suggest a dumbbell bench press. This can ease the stress on the injured shoulder in multiple ways. First, whereas a grip on a barbell is fixed in a somewhat internally rotated position, dumbbells allow for a more neutral grip that can align better with the officer’s structure and ease impinging the shoulder.

Secondly, a dumbbell’s line of movement is malleable. The bar path of a barbell is dictated primarily by the position of the weight bench. Dumbbells allow for rotation of the wrists as it moves through the concentric motion and works the stability of the shoulders individually throughout the entire movement.

If dumbbells are still out of the question for a given injury, replacing them with resistance bands to perform chest flyes — laying on a bench with a weight underneath it to anchor the center of the band — is another reasonable alternative to ease stress off an injury.

Learning training alternatives like this can allow for more consistent training even when a minor injury is sustained. Staying fit while recovering from injury has been shown to improve one’s outlook physiologically and psychologically and return to regular activity with a decreased risk of additional injury. (18)

[Read More: The Most Effective Workout Splits, Created by Our Experts]

SWAT

While the physical fitness standards for Special Weapons And Tactics (SWAT) officers differ from those of a police officer, the benefits of functional fitness training are likely to carry over for those aspiring to join the SWAT unit.

According to SWAT Sergeant David Harrington of the Columbus Division of Police, SWAT officers’ physical fitness is tested quarterly. Similar to the Cooper Standards, SWAT officers are tested for pull-ups, push-ups, sit-ups, and timed for a two-mile run or completion of a functional fitness obstacle course.

While there isn’t a formal SWAT fitness program officers are required to perform in between their quarterly tests, they are allotted time each week while on the clock to train — a perk patrol officers are not privy to.

[Read More: Our Favorite Forearm Workouts, + the Best Forearm Exercises]

Harrington focuses his training on functional fitness, combining strength training and cardio, including high-intensity interval training (HIIT). These workouts consist of multi-plane movements that mimic the activities he often performs on duty while weighted with 40 to 60 pounds of gear. Exercises involve kettlebells, weighted maces, sledgehammer slams, and sled pushes and pulls.

Mental Fitness

Sergeant Harrington expressed the importance of maintaining as consistent a routine as possible when working in law enforcement. Particularly for SWAT officers on call 24/7, maintaining a routine at work, at home, sleep schedule, or training schedule, as best as one can is extremely important.

Given the potential for law enforcement officers to encounter high-stress situations on duty that could lead to traumatic experiences, mental and emotional endurance is as essential as physical fitness. According to the International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, one’s mental fitness suffering due to a traumatic event or burnout can lead to “emotional compassion fatigue” — the cost of caring without reward or result. (19)

Fit to Serve

For those aspiring to join law enforcement and those currently serving, preparing and maintaining strong physical and mental fitness is necessary to perform the requisite duties adequately and have a better quality of life. Functional fitness training and maintaining a routine in the gym and at home are likely to lead to better career longevity. So get a good night’s rest, a solid session in at the gym, and salute your co-workers before heading out for the next shift.

References

- Myers, C., Orr, R., Goad, K., Schram, B., Lockie, R., & Kornhauser, C. et al. (2019). Comparing levels of fitness of police Officers between two United States law enforcement agencies. Work, 63(4), 615-622. doi: 10.3233/wor-192954

- Marins, E., David, G., & Del Vecchio, F. (2019). Characterization of the Physical Fitness of Police Officers: A Systematic Review. Journal Of Strength And Conditioning Research, 33(10), 2860-2874. doi: 10.1519/jsc.0000000000003177

- Lockie, R., Dawes, J., Orr, R., & Dulla, J. (2020). Recruit Fitness Standards From a Large Law Enforcement Agency: Between-Class Comparisons, Percentile Rankings, and Implications for Physical Training. Journal Of Strength And Conditioning Research, 34(4), 934-941. doi: 10.1519/jsc.0000000000003534

- dos Santos, L., Ribeiro, A., Cavalcante, E., Nabuco, H., Antunes, M., Schoenfeld, B., & Cyrino, E. (2018). Effects of Modified Pyramid System on Muscular Strength and Hypertrophy in Older Women. International Journal Of Sports Medicine, 39(08), 613-618. doi: 10.1055/a-0634-6454

- Ribeiro, A., Schoenfeld, B., Souza, M., Tomeleri, C., Venturini, D., Barbosa, D., & Cyrino, E. (2016). Traditional and pyramidal resistance training systems improve muscle quality and metabolic biomarkers in older women: A randomized crossover study. Experimental Gerontology, 79, 8-15. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2016.03.007

- dos Santos, L., Ribeiro, A., Nunes, J., Tomeleri, C., Nabuco, H., & Nascimento, M. et al. (2020). Effects of Pyramid Resistance-Training System with Different Repetition Zones on Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Older Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal Of Environmental Research And Public Health, 17(17), 6115. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176115

- Yorks, D., Frothingham, C., & Schuenke, M. (2017). Effects of Group Fitness Classes on Stress and Quality of Life of Medical Students. Journal Of Osteopathic Medicine, 117(11), e17-e25. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2017.140

- Graupensperger, S., Gottschall, J., Benson, A., Eys, M., Hastings, B., & Evans, M. (2019). Perceptions of groupness during fitness classes positively predict recalled perceptions of exertion, enjoyment, and affective valence: An intensive longitudinal investigation. Sport, Exercise, And Performance Psychology, 8(3), 290-304. doi: 10.1037/spy0000157

- Kraemer, W., Ratamess, N., & French, D. (2002). Resistance Training for Health and Performance. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 1(3), 165-171. doi: 10.1249/00149619-200206000-00007

- LR, A., W, B., MJ, J., & MJ, G. (2021). Simple Bodyweight Training Improves Cardiorespiratory Fitness with Minimal Time Commitment: A Contemporary Application of the 5BX Approach. International Journal Of Exercise Science, 14(3). Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34055156/

- Yamauchi, J., Nakayama, S., & Ishii, N. (2009). Effects of bodyweight-based exercise training on muscle functions of leg multi-joint movement in elderly individuals. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 9(3), 262-269. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2009.00530.x

- Kukić, F., Lockie, R., Vesković, A., Petrović, N., Subošić, D., & Spasić, D. et al. (2020). Perceived and Measured Physical Fitness of Police Students. International Journal Of Environmental Research And Public Health, 17(20), 7628. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17207628

- Larsen, L., Ramstrand, N., & Tranberg, R. (2019). Duty belt or load-bearing vest? Discomfort and pressure distribution for police driving standard fleet vehicles. Applied Ergonomics, 80, 146-151. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2019.05.017

- Bock, C., Stierli, M., Hinton, B., & Orr, R. (2016). The Functional Movement Screen as a predictor of police recruit occupational task performance. Journal Of Bodywork And Movement Therapies, 20(2), 310-315. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2015.11.006

- IМ, O., OM, P., LM, P., OІ, T., LV, H., SS, O., & RМ, P. (2021). THE INFLUENCE OF MODERN SPORTS TECHNOLOGIES ON HEALTH AND PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITY OF LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS. Wiadomosci Lekarskie (Warsaw, Poland : 1960), 74(6). Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34159921/

- Cocke, C., Dawes, J., & Orr, R. (2016). The Use of 2 Conditioning Programs and the Fitness Characteristics of Police Academy Cadets. Journal Of Athletic Training, 51(11), 887-896. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.8.06

- Orr, R., Kukić, F., Čvorović, A., Koropanovski, N., Janković, R., Dawes, J., & Lockie, R. (2019). Associations between Fitness Measures and Change of Direction Speeds with and without Occupational Loads in Female Police

- P, C., & JR, G. (1991). Keeping fit when injured. Clinics In Sports Medicine, 10(1). Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2015643/Officers. International Journal Of Environmental Research And Public Health, 16(11), 1947. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16111947

- JM, V., & A, G. (2004). Police trauma encounters: precursors of compassion fatigue. International Journal Of Emergency Mental Health, 6(2). Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15298078/

Featured image via Shutterstock/Flamingo Images