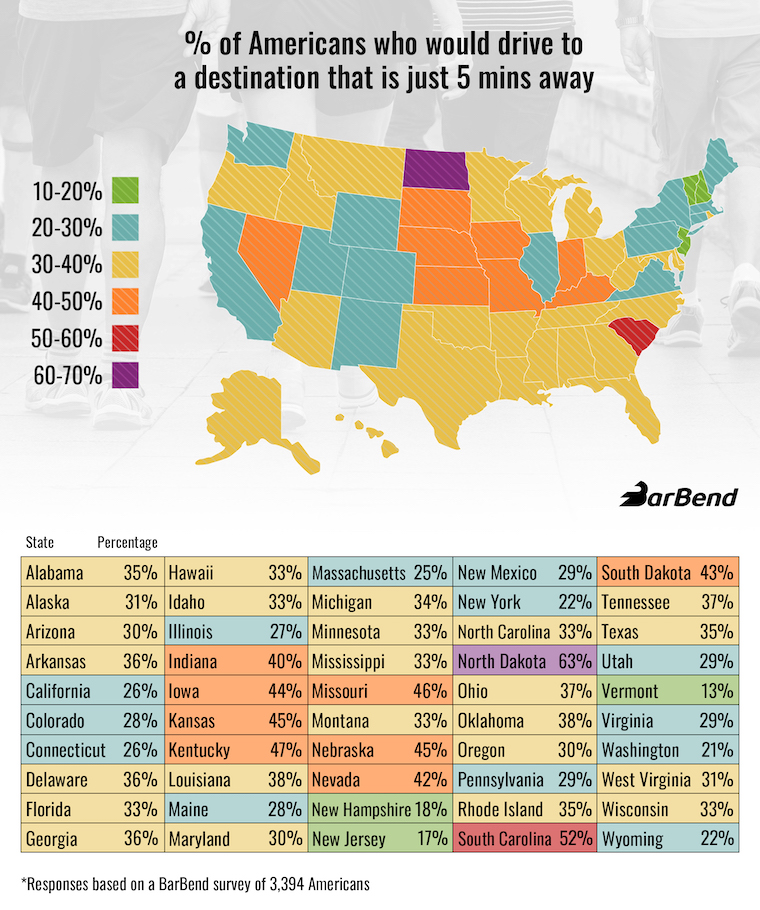

Are Americans lazy? That question is likely too broad, but the implication is not. According to a new survey of 3,394 Americans across all 50 states conducted by BarBend, when given a binary choice to drive or walk to a destination that is a five-minute walk away, over a third of Americans would rather drive. (1)

Out of all 50 states, the most significant percentage of respondents who would drive the five-minute walk live in North Dakota. A whopping 63 percent of the northern midwest state would hop in their car for the short trip. The second state with the highest percentage is in the southeast — South Carolina at 52 percent.

Another seven states are home to plus-40 percent of respondents opting for a vehicle rather than traveling on foot — Nevada, Nebraska, Missouri, Kentucky, Kansas, Iowa, and Indiana. On the opposite end of the spectrum, only three states were sub-20 percent — New Hampshire, New Jersey, and Vermont.

[Related: Reasons Walking Is the Most Underrated Exercise]

The national average of people who would drive rather than walk a five-minute walk away is 32 percent**.

**32 percent is tabulated only via respondents that entered their state location. When all states’ percentages are averaged together, the number rises to 33.28%.

A state’s population does not appear to have any impact on this survey’s findings. According to World Population Review, the least populated state is Wyoming (581,075), followed by Vermont (623,251). Both states are on the lower end of the spectrum, with only 22 percent and 13 percent of respondents, respectively, stating they would, in fact, rather walk to a destination that’s a five-minute walk away.

However, North Dakota (770,026) and South Dakota (896,581) are the fifth and sixth least populated states, respectively, and sit at the higher end of the dataset. The two most populated states — California (39,613,493) and Texas (29,730,311) — are separated by 21 ranks in the data set. Texans would drive the five-minute walk nine percent more often than Californians.

Despite one in three people opting to drive rather than walk a short distance, 41 percent of respondents believe they do not walk enough each day.

So what could be some of the reasons Americans opt for the path of least resistance to journey a short five-minute walk?

Temperature

The weather undoubtedly plays a factor in Americans’ willingness to walk outside, regardless of distance. The colder the weather, the more Americans would opt for a vehicle, with the steepest increase striking at exactly freezing temperature (32 degrees Fahrenheit). Per BarBend‘s survey, below is the breakdown of temperatures Americans would choose to drive rather than walk:

Note: all temperatures are in Fahrenheit.

- 32 degrees — 60 percent

- 36.5 degrees — Eight percent

- 41 degrees — Six percent

- 45.5 degrees — 11 percent

- 50 degrees — Seven percent

- 54.5 degrees — Two percent

- 59 degrees — Eight percent

For reference, people who choose to walk are likely to get to their destination faster in colder temperatures. Walking speed is found to be faster in winter than in summer by approximately .03 meters per second. (2) That is to say, an American walking a five-minute distance in winter will get there while their summer-walking counterpart has nine meters to go.

[Related: These Researchers Reveal the Right Way to Train for More Muscle Mass]

Temperature isn’t the only factor, though. Even when indoors, nearly one-third of respondents would opt for an elevator for any destination above three flights.

Obesity in the USA

Although BarBend‘s survey did not consider respondents’ body fat percentages, obesity prevalence in the USA has risen steadily since 1999, despite a leveling off between 2009 and 2012 and increasing again after that. (3) More than half of the US population (51 percent) is expected to be obese (body mass index (BMI) greater than 30) by 2030. (4).

A 2019 study in The New England Journal of Medicine found suggests that no state will have an obesity rate below 35 percent in 2030, with nearly a quarter of all adults suffering from severe obesity (BMI greater than 35). (5) Per Trust for America’s Health, which is funded, in part, by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the obesity rate in America in 2020 reached 42.5 percent.

National surveys have shown obesity rates to have an inverse relationship to active transportation (e.g., walking, biking, etc.) compared to passive transportation (e.g., driving, bussing, train, etc.). (6) Countries where active transportation is higher, obesity rates are lower. For example, 16 European countries — Albania, Austria, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Croatia, England, Finland, France, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Poland, Romania, Spain, and Sweden — have an average obesity rate of 12.8 percent among adults. Each year, Europeans traverse 3.2 times more distance via active transportation than Americans. (7)

Although BarBend‘s survey suggests that Americans will opt for passive means of transportation, choosing to walk rather than drive when feasible could dent the USA’s obesity trajectory.

[Read More: Best Treadmills for Walking, CPT Approved]

Benefits of Walking

Walking is “a year-round, readily repeatable, self-reinforcing, habit-forming activity” and is considered a “main option” for promoting more physical activity for otherwise sedentary communities, per Sports Medicine. (8) Aside from unique cases among those injured or otherwise physically frail, walking requires no equipment, specific skills, or particular venue to perform. It can be effective at accelerating one’s heart rate to 70 percent of their maximum. Walking for just six minutes at a non-leisurely pace can elevate one’s heart rate within three percent of that threshold. (9)

For individuals, walking can lower their risk of heart disease, reduce their anxiety and tension, improve their cholesterol profile, and help with weight loss when performed consistently. (10) For the national population, increasing the amount of walking each day can reduce rates of chronic disease and relieve some pressure of rising health care costs. (11)

[Read More: Best Cross-Training Shoes (Personally Tested)]

Take a Walk

Of course, there can often be factors outside your control when attempting to get your steps in each day. Perhaps the weather creates many hurdles, or you have to carry items that are too heavy. But when walking or driving to a destination is feasible, maybe you should opt for your walking shoes rather than your car keys. Those steps add up over time to a healthier lifestyle long-term.

References

- Google Surveys; October 2021; 3,394 respondents; Ages 18+; Survey Methodology)

- Obuchi, S. P., Kawai, H., Garbalosa, J. C., Nishida, K., & Murakawa, K. (2021). Walking is regulated by environmental temperature. Scientific reports, 11(1), 12136. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91633-1

- Wang, Y., Beydoun, M. A., Min, J., Xue, H., Kaminsky, L. A., & Cheskin, L. J. (2020). Has the prevalence of overweight, obesity and central obesity levelled off in the United States? Trends, patterns, disparities, and future projections for the obesity epidemic. International journal of epidemiology, 49(3), 810–823. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyz273

- Finkelstein, E. A., Khavjou, O. A., Thompson, H., Trogdon, J. G., Pan, L., Sherry, B., & Dietz, W. (2012). Obesity and severe obesity forecasts through 2030. American journal of preventive medicine, 42(6), 563–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.026

- Ward, Z. J., Bleich, S. N., Cradock, A. L., Barrett, J. L., Giles, C. M., Flax, C., Long, M. W., & Gortmaker, S. L. (2019). Projected U.S. State-Level Prevalence of Adult Obesity and Severe Obesity. The New England journal of medicine, 381(25), 2440–2450. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1909301

- Bassett, D. R., Jr, Pucher, J., Buehler, R., Thompson, D. L., & Crouter, S. E. (2008). Walking, cycling, and obesity rates in Europe, North America, and Australia. Journal of physical activity & health, 5(6), 795–814. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.5.6.795

- Gallus, S., Lugo, A., Murisic, B., Bosetti, C., Boffetta, P., & La Vecchia, C. (2015). Overweight and obesity in 16 European countries. European journal of nutrition, 54(5), 679–689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-014-0746-4

- Morris, J. N., & Hardman, A. E. (1997). Walking to health. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 23(5), 306–332. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-199723050-00004

- Corrêa, F. R., da Silva Alves, M. A., Bianchim, M. S., Crispim de Aquino, A., Guerra, R. L., & Dourado, V. Z. (2013). Heart rate variability during 6-min walk test in adults aged 40 years and older. International journal of sports medicine, 34(2), 111–115. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1321888

- Rippe, J. M., Ward, A., Porcari, J. P., & Freedson, P. S. (1988). Walking for health and fitness. JAMA, 259(18), 2720–2724.

- Lee, I. M., & Buchner, D. M. (2008). The importance of walking to public health. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 40(7 Suppl), S512–S518. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817c65d0

Feature image via Shutterstock/VanoVasaio