In March 2018, The New York Times estimated that in the United States alone, the nutritional supplement industry was worth roughly $133 billion.(1) While the newspaper seemed somewhat shocked at the size of the supplement industry, for gym goers, such figures intuitively make sense. When was the last time you didn’t see someone swig a protein shake after a tough workout or slam some pre-workout before a heavy set of squats?

Since beginning my own lifting career over a decade ago, it has become easier and easier to consume protein shakes, bars, and brownies than ever before. My local supermarket sells creatine and branched chain amino acids. Heck, my own father now takes whey protein because of its supposed benefits for older individuals’ bone health.(2)

All of this begs a simple question: how long have individuals turned to nutritional supplements in search of an extra edge? While we could begin several centuries ago in Ancient Greece when athletes supposedly drank wine as a health food, or several centuries ago when fish oils began to be used, it seems prudent to look instead at commercially made products such as protein powders or vitamin extracts.(3) After all, health foods have existed for millennia; health supplements are a far more recent occurrence. With this in mind, today’s post traces the history of bodybuilding supplements from their early beginnings in the late nineteenth-century right up until the present day.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bp_qBOogcmO/

Plasmon, Bovril and Iron Jelloids, the Early Supplements

As detailed by Steinitz, the late nineteenth-century was witness to a food innovation that just about every gym goer owes thanks for: the creation of milk based powders.(4) Though ‘protein powders’ are a relatively recent phenomenon, the process of separating whey and casein from milk and then converting them into powders arose in the late 1800s.(5) This innovation stemmed not from the lifting community but rather from the burgeoning world of European medicine. Originating in mainland Europe, milk based powders found commercial expression in products such as Plasmon, a dehydrated dairy product that is the first of our bodybuilding supplements examined today.

[Learn more about the differences between whey and casein protein powder here.]

Plasmon

Produced in Germany but subsequently marketed in Great Britain, Plasmon was the nutritional supplement par excellence. Emerging in England in the late 1890s, Plasmon soon took the lifting community by storm.(6) As covered previously on BarBend, England was the hub of strength training activities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth-century. While the ‘mecca’ would soon pass to America’s west coast, the early years of lifting were defined by the English community.

So when Plasmon began receiving celebrity endorsements, consumers took notice. Within the first decade of the twentieth-century, Plasmon could count upon its users Eugen Sandow, the man many regard as the father of modern bodybuilding, Eustace Miles, a famed athlete and health expert, and even Ernest Shackleton, the famed South Pole Explorer.(7) While the latter men were undoubtedly famous, neither could match Sandow’s popularity. Thus when Sandow deemed Plasmon an excellent strength builder, those seeking to emulate his physique flocked to stores to purchase the product for themselves.

Bovril

Although Plasmon was the most popular supplement of its time, it was not the only thing lifters sought to get their hands on. Equally important was Bovril, a distinctly English drink which contains amongst its various ingredients diluted beef extract.(8) Promoted as a ‘body builder’ in its own right and described by Wikipedia as “a thick and salty meat extract paste,” Bovril was advertised extensively in English newspapers in the late 19th century as a fantastic ‘flesh forming’ food. In layman’s terms, this meant that it would help people put on weight.

Though its popularity paled in comparison to Plasmon, Bovril was nevertheless a mainstay for early lifters and counted amongst its endorsers the Indian club swinger Tom Burrows and significantly better known Arthur Saxon.(9)

[See how far we’ve come — check out our list of the best women’s fat burner supplements.]

Iron Jelloids

Just as in today’s market, celebrities were not afraid to promote more than one supplement at any one time. Burrows, a man famed for swinging Indian clubs for over one hundred hours without rest, similarly promoted ‘iron jelloids’ during this time.(10) Despite my best efforts, I’ve been unable to track down the full history of iron jelloid supplements so I’m happy to console myself with the broadly supported idea that they were more or less gummy bears stuffed full of liver.

Cocoa

Last but not least, was cocoa. Long before twenty-first century gurus touted the nutritional benefits of cocoa, early weightlifters were turning towards a variety of cocoa powders in search of muscle gain and energy retention. Though it may seem strange to us now, cocoa was one of the most highly sought after supplements of the early 1900s. (And to be fair, science has found it to be a pretty effective supplement for pump.)

[Read more: The Best and Worst Fitness Tips from Old Timey Strongmen.]

Said to increase both brain and nerve power, the cocoa market was dominated by two figures. The first was Eugen Sandow, a man we have covered extensively. Beginning in 1911 and continuing until the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, Sandow’s cocoa was used by gym goers, the general public and even doctors to treat illnesses.(11)

There was just one problem: Sandow’s cocoa was made in Germany, so when England declared war on Germany in 1914 Sandow’s reputation and supply line drastically dropped, much to the delight of his competitor, Cadburys.(12) For perhaps obvious reasons, the other large scale producer of nutritional cocoa was Cadburys, better known for their chocolate bars rather than their health supplements. As shown by Chapman, Cadburys and Sandow battled it out for supplement supremacy during this period, a battle Cadburys eventually won.(13) When the Great War finally ended in 1918, Cadburys were the main suppliers of nutritional cocoa.

For early physical culturists, or “strength athletes” to you and me, the market for supplements was relatively straightforward. For a short while you could choose between plasmon, bovril, iron jelloids, or cocoa. That is not to say that other supplements did not exist but rather that these four represented the most popular and freely available. Remarkably, the Iron Game would have to wait until the 1930s for new innovations in bodybuilding supplements tentatively began to hit the market.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BomCT8VB–2/

The Protein Pushers: Supplements in the 1960s

Echoing shifts in the broader political realm, the 1930s and 40s saw Britain’s dominance in the realm of physical culture fall dramatically. Whereas once London was the hotbed of activity for weightlifters, strongmen, and entrepreneurs, attention now turned towards the United States, whose bodybuilding reputation was beginning to rise.

As explained by Roach, it was during this time that Eugene Schiff, a young pharmacist in the United States created Schiff Bio-Foods, a natural supplement company whose primary product was whey protein.(14) While Plasmon had led the way in this regard three decades previously, its popularity had fallen dramatically by 1914. With no other obvious replacement, Schiff’s products were thus incredibly unique. Equally important was Schiff’s emphasis on other natural supplements such as brewers yeast, wheat germ, Vitamin C and liver, all of which became bodybuilding staples by the 1950s and 60s.(15)

[Don’t miss our picks for the best whey protein powders you can buy.]

While Schiff’s products remained at the fringes of the Iron Game, they alerted others to the possibilities offered by supplements. In a fantastic study of early protein supplements, Hall and Fair detailed a remarkable meeting between Paul Bragg and Bob Hoffman in 1946. For those unaware, Bragg was one of the most popular nutritional advisers in twentieth-century America. Promoting fasting, healthy eating and distilled water, Bragg was the inspiration for Jack Lalanne, whose motto that the only healthy part of a donut is the hole, remains my favorite catchphrase.(16)

Hoffman on the other hand, is often considered the father of American weightlifting. Owner of the then highly successful York barbell and patron to the US Olympic weightlifting team, Hoffman had, in Bragg’s eyes, a unique business opportunity. Writing to Hoffman in 1946, Bragg told him:

I believe, Bob, that we can really add a tremendous income to your earnings, because the food business is not like the athletic equipment business. In 1913 I bought a set of barbells from the Milo Barbell Company and today they are just as fine as they were way back there in the dim past. But when you get thousands of your students eating your food and they consume it, you have no idea of the tremendous income that you will have rolling in.(17)

Somewhat frustratingly for Bragg, the proposed collaboration to make health food came to nothing after Hoffman’s idea for a protein bread failed to impress. Nevertheless a tentative step towards the industry we know today had been made.

Returning to Roach’s work on the subject, we learn that four years after Bragg’s proposals, a company called Kevo Products produced ‘44’, a soy based protein powder geared towards athletes.(18) A similar product, this time advertised as a meal replacement titled ‘B-Fit’ also emerged at this time.

But what of Bob Hoffman and York? Had he been inspired by Bragg? Most likely no, but he was inspired by profit. Finally aware of the market Bragg foretold, York Barbell entered the protein game in 1952 with with ‘Hi-Proteen’ protein powder.

What had changed? Well in 1951, Irving Johnson (later known as Rheo H. Blair), began advertising his own Hi-Protein supplement in the pages of Hoffman’s Strength and Health magazine. Now acutely aware of the demand for such products, Hoffman cut ties with Johnson and produced his own powder, much to the chagrin of Johnson, who don’t worry, we will be returning to.(19) Eventually coming in chocolate, vanilla, black walnut, coconut, and plain, Hoffman’s supplement promised easy and impressive results. For just $4 (roughly $40 in current money), customers were told they would have access to an advanced soy based powder produced with the ‘latest’ advances in technology.

Jim Murray, Hoffman’s managing editor, later revealed that Hoffman’s product was actually created by Hoffman in the old York enterprises. Hoffman would dump a bag of Hersey’s sweet chocolate into a vat and stir in soybean flour with a paddle. Stirring vigorously Hoffman would continue to taste the blend until he found a palatable mixture.(20) Science at its finest, am I right folks?

https://www.instagram.com/p/Ba3upiyAfu8/

Despite his questionable methods, Hoffman was responsible for many of the products still used today. Beginning with his questionable soy protein formula, Hoffman and York would prove to be pioneers in the marketing of protein bars, protein treats, vitamin supplements and a host of other everyday supplements. While some of these products, such as Hoffman’s fish based protein, failed to stand the tests of time (or in this case, the tastes of time), they nevertheless set a precedent for others in the market.(21) While no one can deny the business acumen of the Weider brothers, Joe and Ben’s early bodybuilding business was largely characterised by their efforts to mimic Hoffman’s supplements and magazines with a new Weider twist.(22)

The 1960s therefore saw an explosion of bodybuilding supplements and at a time when steroid use was still the Iron Game’s dirty little secret, many believed that these supplements in fact worked wonders. Returning to Irving Johnson, who rebranded himself as Rheo H. Blair during this time, Blair’s protein powders, liver extracts and amino acid tablets became highly sought after. Thus, bodybuilding accounts from this time recount stories of Frank Zane taking handfuls of Blair’s Amino Acids every few hours or Vince Gironda putting clients on a strict regimen of Blair supplements.(23)

At a time when the effects of steroids were still uncertain, Vince was adamant that a regimen of desiccated liver, raw eggs and various other health foods could match dianabol’s anabolic properties.(24 Aside from protein powders, many exotic sounding supplements no longer in use by mainstream gym goers such as choline, brewer’s yeast, inositol and wheat germ enticed thousands by their promises of unbridled health and greater muscle gain.

More Familiar Faces: Supplements Since the 1980s

While the supplements outlined above represented the bulk of the gym goer’s arsenal for the remainder of the century, innovations in food supplements were by no means slowing down. Short-lived interest in arginine, lysine and ferulic acid in particular emerged in the 1980s before dying away.(25)

Rise of the Pre-Workout

Far more enduring supplements did arise during this time however. The first, and arguably most revolutionary supplement emerged: the pre-workout powder. Produced in 1982 by Dan Duchaine of Body Opus and Underground Steroid Bible Fame, Ultimate Orange marked the industry’s first pre-workout supplement designed solely to amp people up before their workouts.(26)

While Ultimate Orange was ultimately outlawed owing to a series of court cases oftentimes, centring on its inclusion of ephedra, its popularity spawned a generation of copycat supplements, many of which are regularly features in locker rooms and gym floors. The emergence of pre workout blends also advanced the use of branched chain amino acids, many of which were thrown into pre-workout mixes for the fun of it.

[Take a look at our guide to the best pre-workouts on the market.]

https://www.instagram.com/p/BqSND_Rl7I4/

Enter Creatine

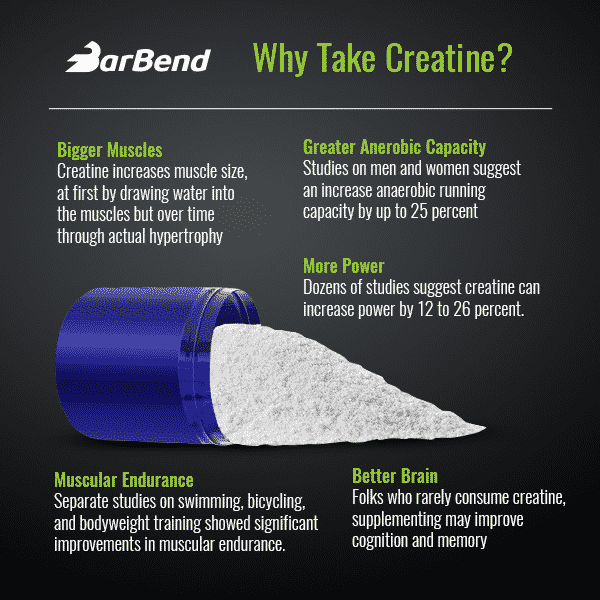

Despite the rave reviews it received from consumers, Ultimate Orange lacked one ingredient now seen as absolutely crucial for the weightlifting community: creatine. While creatine had been used experimentally with athletes for two decades by this point, it wasn’t until 1993 that a creatine supplement was marketed for the mass public.(27) Produced first by Experimental & Applied Sciences or EAS, creatine’s notoriety grew during the 1990s after a series of high profile athletes and a series of Olympic gold medalists revealed they took a substance many viewed as dubious.(28) Amazingly, creatine’s reputation as a safe and effective product has undergone a remarkable revision over the past two decades to the point where it is arguably one of the most widely used and recommended substances around.

[Check out our full roundup of the best creatine supplement on the market – where does your favorite land?]

On Prohormones

Funnily enough, while the media demonized creatine, an actually dubious product hit the market. First produced by Patrick Arnold in 1996, prohormones promised steroid like results with none of the side effects.(29) They were over the counter and widely available as several sports stars soon discovered. In the US, prohormones came to media attention following Mark McGwire’s revelation that he used the prohormone androstenedione during his record home run season with and it took a massive sporting scandal to draw attention to it.(30)

For readers who can remember this period, the prohormone craze went into overdrive during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Supplement shops offered a wide array while the internet turned into a veritable Wild West of shady products. Eventually the US government stepped in and decided to put a stop to such practices through the Anabolic Steroid Control Act of 2004.(31) Though effective, the Act did not completely stop the trade in prohormones, as demonstrated by a revised 2014 Act, which banned several dozen more prohormones. The birth, rise and ultimately fall of prohormones during this time serves as a reminder that not all supplements can be harmless.

ZMA

Finally and detailing my own interest in sleeping as deeply and for as long as possible, the late 1990s witnessed the emergence of ZMA (Zinc monomethionine aspartate, magnesium aspartate, and Vitamin B6) as a supplement. Produced by Victor Conte, a man later embroiled in a sport steroid scandal, ZMA promised steroid like increases to testosterone alongside some pretty wacky dreams.(32) Initial ZMA studies promised a wonderdrug like product while the co-option of sports’ stars such as Marion Jones and Barry Bonds meant that athletes and bodybuilders flocked in droves to pick up this latest mineral compound.(33) While subsequent studies has cast aspersions on ZMA’s purported benefits, it’s popularity amongst gym goers has continued. If nothing else, it usually gives me vivid dreams which can be equal parts scary and fun.

Summing Up

Nowadays supplements have permeated our lives. In my own town I can get protein bars from my local garage, my gym stocks protein donuts, and if I’m feeling particularly peckish, I can buy protein crisps from the nearest supermarket. Similarly I can get small packets of creatine or BCAAs through vending machines in my own university. Needless to say, it’s never been easier to access supplements.

References

- Kari Molver, ‘Next-Generation Superfood Supplements — With Beauty Benefits’, The New York Times Style Magazine, 02 July 2018, accessed 22 November 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/14/t-magazine/superfood-supplements.html.

- Keri Marshall, ‘Therapeutic Applications of Whey Protein’, Alternative medicine review 9.2 (2004): 136-157.

- Stephen G. Miller, Ancient Greek Athletics. Yale University Press, 2006, p. 85; Bo Martinsen, ‘How Has Cod Liver Oil Changed Over the Last Century?’, 31 October 2016. Accessed 17 November, 2018, https://omega3innovations.com/blog/how-has-cod-liver-oil-changed-over-the-last-century/.

- Lesley Steinitz, ‘The Language of Advertising: Fashioning Health Food Consumers at the Fin de Siècle’, in Food, Drink, and the Written Word in Britain, 1820–1945, eds. Mary Addyman, Laura Wood, Christopher Yiannitsaros (London: Routledge, 2017), 135-163.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- See Plasmon Ltd., Plasmon: The Mainstay of Life – What is It? (London: International Plasmon Ltd., c. 1906).

- Michael Anton Budd, The Sculpture Machine: Physical Culture and Body Politics in the Age of Empire. NYU Press, 1997, p. 39.

- Graeme Kent, The Strongest Men on Earth: When the Muscle Men Ruled Show Business. Biteback Publishing, 2012, pp. 65-80.

- ‘Iron Jelloids’, The Liverpool Echo, 20 May 1914, p. 6.

- Dominic G. Morais, ‘Branding Iron: Eugen Sandow’s “Modern” Marketing Strategies, 1887-1925’, Journal of Sport History 40.2 (2013), pp. 193-214.

- David L. Chapman, Sandow the Magnificent: Eugen Sandow and the Beginnings of Bodybuilding. University of Illinois Press, 1994, pp. 170-175.

- Ibid.

- Randy Roach, Muscle, Smoke, and Mirrors, Volume 1, Bloomington, 2008, pp. 132-140.

- Ibid.

- Daniel T. Hall and John D. Fair, ‘The Pioneers of Protein’, Iron Game History, May/June (2004): 23-34

- Ibid.

- Roach, Muscle, Smoke, and Mirrors, p. 197.

- John D. Fair, Muscletown USA: Bob Hoffman and the Manly Culture of York Barbell. Penn State Press, 1999, pp. 147-148.

- Ibid.

- Roach, Muscle, Smoke, and Mirrors, p. 624.

- Hall and Fair, ‘The Pioneers of Protein’, p. 33.

- Ibid.

- Roach, Muscle, Smoke, and Mirrors, pp. 463-464.

- James Collier, ‘Supplements of Yesteryear’, Muscletalk. Accessed 15 November 2018, https://www.muscletalk.co.uk/articles/article-supplements-of-yesteryear.aspx.

- Shaun Assael, Steroid Nation: Juiced Home Run Totals, Anti-Aging Miracles, and A Hercules in Every High School: The Secret History of America’s True Drug Addiction. New York, NY: ESPN Books, 2007, p. 140.

- Brittain, Harry G., ed. Profiles of Drug Substances, Excipients and Related Methodology: Critical Compilation of pKa Values for Pharmaceutical Substances. Elsevier, 2007, p. 3.

- Kirk Bizley, Examining Physical Education. Heinemann, 2000, p. 111.

- Mark Fainaru-Wada and Lance Williams. Game of Shadows: Barry Bonds, BALCO, and the Steroids Scandal that Rocked Professional Sports. Penguin, 2006, p. 53.

- Ibid., pp. 53-60.

- Marie Dunford, , and J. Andrew Doyle. Nutrition for Sport and Exercise. Cengage Learning, 2011, p. 441.

- Louise Burke, Practical Sports Nutrition. Human Kinetics, 2007, p. 479.

- Fainaru-Wada and Williams. Game of Shadows, pp. 3-4.